Book comes out as part of an ongoing celebration of the 50th anniversary of President Kennedy’s first year in office

NEW YORK (AP) ― It’s a side of Jacqueline Kennedy only friends and family knew. Funny and inquisitive, canny and cutting.

In “Jacqueline Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life With John F. Kennedy,” the former first lady was not yet the jet-setting celebrity of the late 1960s or the literary editor of the 1970s and 1980s. But she was also nothing like the soft-spoken fashion icon of the three previous years. She was in her mid-30s, recently widowed, but dry-eyed and determined to set down her thoughts for history.

In the conversations, she refers to France’s Charles de Gaulle, whom she had famously charmed on a visit to Paris, as “that egomaniac” and “that spiteful man.” Indira Gandhi, the future prime minister of India, was a “prune ― bitter, kind of pushy, horrible woman.”

Kennedy met with historian and former White House aide Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. in her 18th-century Washington house in the spring and early summer of 1964. At home and at ease, as if receiving a guest for afternoon tea, she chatted about her husband and their time in the White House. The young Kennedy children, Caroline and John Jr., occasionally popped in. On the accompanying audio discs, you can hear the shake of ice inside a drinking glass. The tapes were to be sealed for decades and were among the last documents of her private thoughts. She never wrote a memoir and became a legend in part because of what we didn’t know.

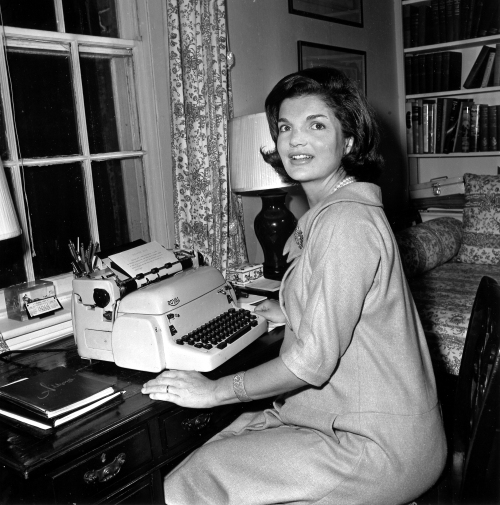

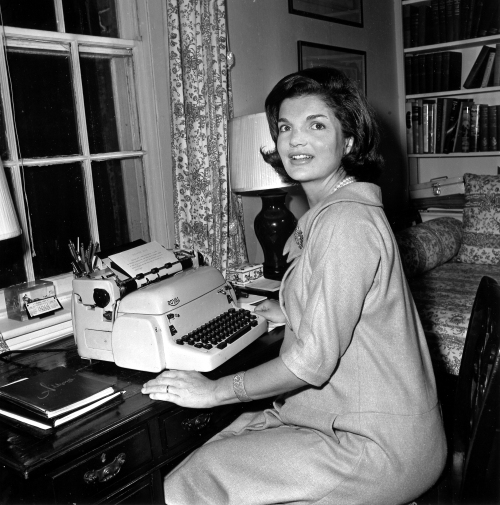

|

Jacqueline Kennedy poses at her typewriter where she wrote her weekly “Candidate’s Wife” column in her Georgetown home in Washington, Oct. 5, 1960. (AP-Yonhap News) |

The book comes out Wednesday as part of an ongoing celebration of the 50th anniversary of President Kennedy’s first year in office. Jacqueline Kennedy died in 1994, and Schlesinger in 2007.

The world, and Jacqueline Kennedy, would change beyond imagination after 1964. But at the time of these conversations black people were still Negroes and feminists were still suspect even in the view of a woman as sophisticated as Kennedy, who a decade later would grant an interview to Gloria Steinem’s Ms. magazine. In the book’s foreword, Caroline Kennedy faults Schlesinger for asking so few questions about her mother.

As historian Michael Beschloss notes in the introduction, Jacqueline Kennedy once accepted that wives were defined by their husbands’ careers and worried about “emotional” women entering politics. She enjoyed having her husband “proud of her,” saw no reason to have a policy opinion that wasn’t the same as his and laughed at the thought of “violently liberal women” who disliked JFK and preferred the more effete Adlai Stevenson.

“Jack so obviously demanded from a woman ― a relationship between a man and a woman where a man would be the leader and a woman be his wife and look up to him as a man,” she said. “With Adlai you could have another relationship where ― you know, he’d sort of be sweet and you could talk. ... I always thought women who were scared of sex loved Adlai.”

There are no spectacular revelations in the Schlesinger discussions and virtually nothing about JFK’s assassination. Kennedy’s health problems and his extramarital affairs were still years from public knowledge and from the knowledge of aides such as Schlesinger, who would often say he saw no “bimbos” in the White House halls.