Happiness and ‘specs’

“Are you happy?” is a simple question to which Rashid never got a straightforward answer.

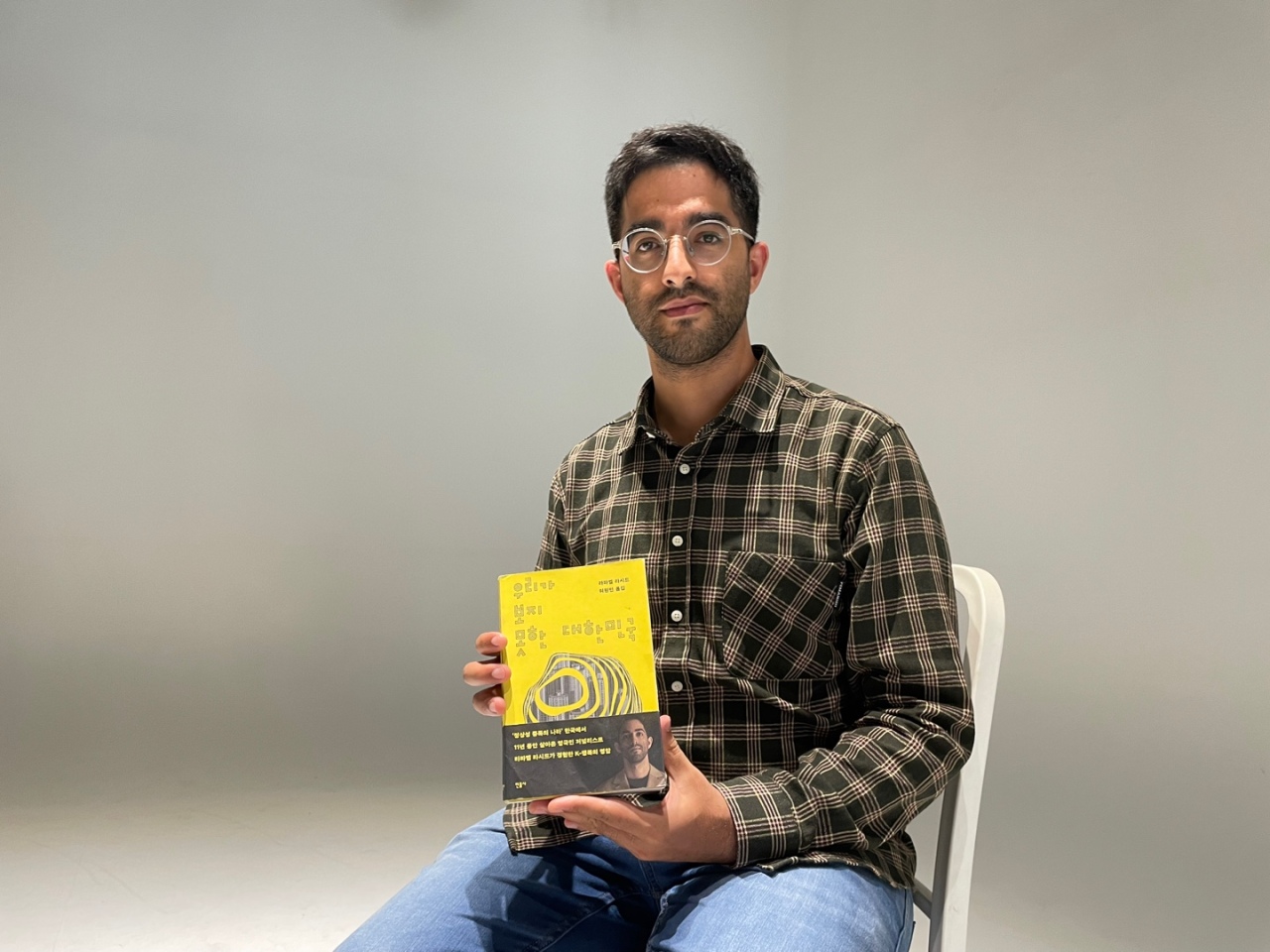

“I‘ve never really been able to get a straightforward answer without any hesitation, and I’ve always kind of wondered why people around me, friends included, can‘t necessarily answer this question when on the outside everything seems to be working in their favor -- they have good jobs, went to a good university … they have everything. Yet, maybe not very happy,” Rashid said.

“And a lot of times I feel like I’ve become a counselor over the past 10 years, like a back for people to cry on. … And so I thought I‘d kind of try to summarize all of these things and put it all in a book.”

One of the reasons for this may be the relentless drive for “specs” -- a Korean neologism based on the abbreviation used to describe the specifications of a PC -- referring to certain qualifications or expectations that people are expected to fulfill in order to attain a desired outcome, whether it be to get into a company, school, or even a relationship.

Rashid likened accumulating specs to checking off a to-do list or following a manual.

“It’s like a checklist, and many people have the same checklist … things like marriage or getting into a good company,” he said, adding, “I don‘t want to generalize, but it feels like many people need to achieve the same things. Otherwise, maybe they feel like they’re falling behind.”

This is one of the reasons for many Koreans’ unhappiness, Rashid explained.

“I think the cracks will eventually show, and dating or marriage I think is one of the big ones, because we’re now seeing South Korea (having) one of the highest divorce rates in Asia.”

A country of black and white reasoningAnother reason for many Koreans’ malaise may be the “black and white reasoning” that colors a lot of the public discourse and social behavior of Koreans, according to Rashid.

“In Korea, it‘s either left or right. You’re either for, you‘re against. You’re either conservative or liberal. You‘re either a masculine male or a feminine woman. You have a lot of these very clear divides in Korea,” he said. “And ultimately, I think a lot of these divides are getting more severe in society and create a lot of friction.”

In the book, Rashid recalls giving a presentation about North Korea for a university class. He was interrupted by his Korean professor during his presentation, who interrogated him about which side he was on, North or South.

This is emblematic of how there is so little room for discussion or debate, and how one can be shut down if the other person disagrees with one’s narrative or interpretation of a situation or topic. Rashid goes on to illustrate examples in the book this tendency to view issues in terms of right versus wrong, winners and losers, in ways that go beyond geopolitics – into debates about gender equality, ethnic minorities and human rights.

‘Desirable v. undesirable’ foreignersFor some Koreans, Rashid’s book is more of a nuisance. With many TV programs featuring foreigners residing in South Korea who have nothing but praise for the country, his perspective is hard to swallow for some. But he has refused to turn a blind eye to the underbelly of Korean culture against the relentless pushing of a shiny, sanitized image.

Rashid recalled his meeting with a staff member from one such TV program featuring foreigners in Korea. While considering topics of discussion, he said that he was interested in social justice and human rights issues. The staff member became confrontational and asked him if he even “liked” South Korea, adding that the show was about “complimenting” the country – the exact word that the staff member used, Rashid pointed out. Needless to say, he did not end up going on the program.

“So there’s that kind of expectation for foreigners to only say the good stuff. And the minute you say something bad, then people might not like it,” Rashid said. He also pointed out the persistent underlying racism in Korean media’s depictions of foreigners, which subtly reinforce racialized stereotypes.

“There’s no exact formula, but it’s usually white, Western, from Europe or North America … (those) are the desirable foreigners,” he said. “And then you have the undesirable foreigners who are from countries less well-off. … (They) are the subjects of these so-called human documentaries who are in need of help, or are unfortunate, who are suffering.”

What’s changed?

When asked about the biggest change in Korea over the past ten years, Rashid said that more and more people – especially younger Koreans – are speaking up against injustices. He brought up the impeachment of former President Park Geun-hye and the rise of women’s protests against illegal spycams as examples, against a general backdrop of more visible social justice movements worldwide.

“Civil society has been able to get together a lot more in a more concerted way, fighting for people’s rights, and so when something is wrong we‘ll know about it ... people are not going to stay silent anymore,” he said.

However, conflicts over gender equality and social hierarchy persist, he cautioned.

“There’s a conflict between the old and the new … and I think it‘s not going to change overnight. But I see a lot of hope in the young generation,” he said.

While he has no solutions for the issues he raises in the book, an important question to ask is: “Is it really worth it?” On his own happiness, Rashid candidly spoke of his own journey. While growing up and coming of age back in the UK and for some time in Korea, he was not always happy, following what was expected of him.

“But when I finally realized that I don’t need to follow what everyone else does, then I had this kind of sense of relief and release,” he said. “I’ve seen some people passing away around me in Korea, and these tragic events have made me realize that life is not infinite and we should cherish and be happy with what we already have, rather than chase distant dreams that might not ever be realized. So the short answer is: I’m happy.”

By Park Ga-young and Beth Eunhee Hong (

gypark@heraldcorp.com)(bethhong@heraldcorp.com">

gypark@heraldcorp.com)

(bethhong@heraldcorp.com)