|

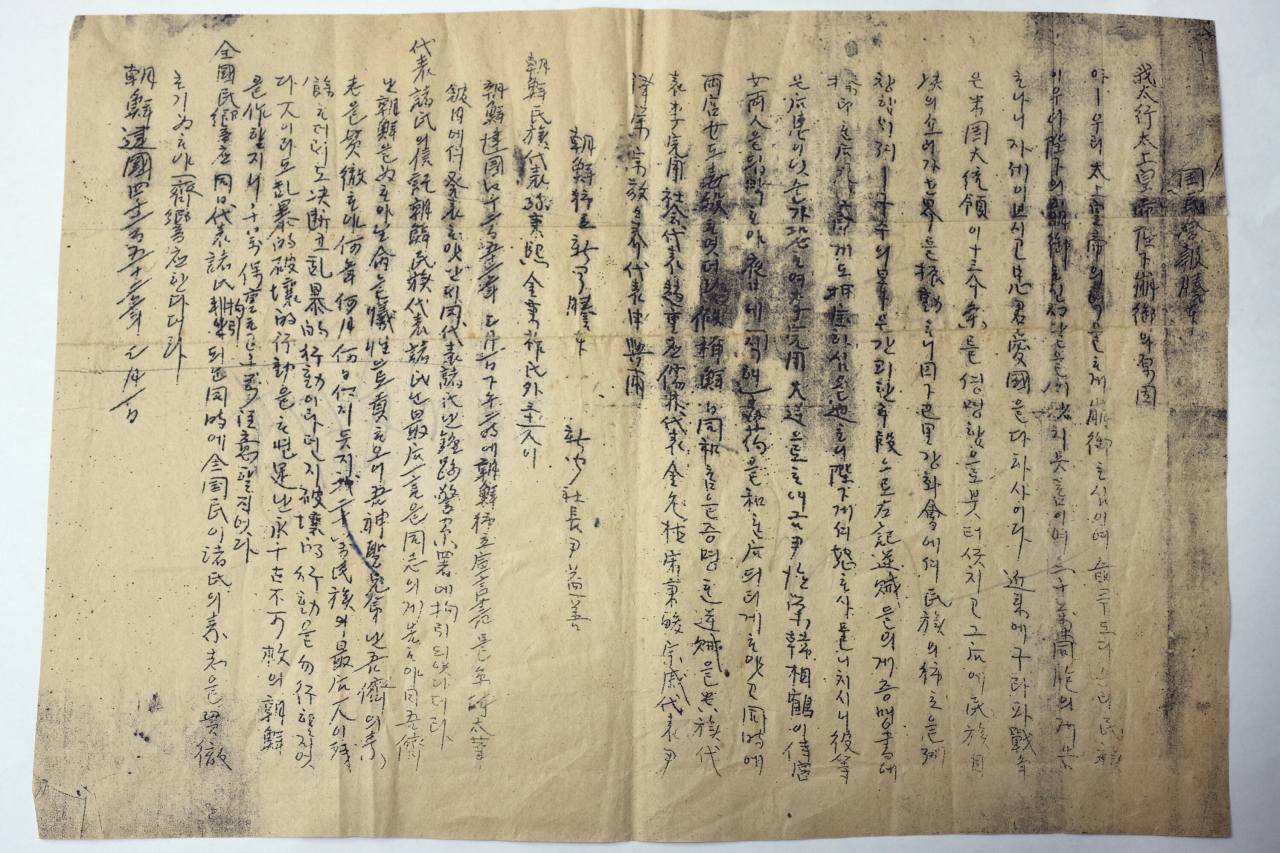

Bohyeonsa beopdang, which was moved from Daegu to Yonghwasa in Yeongcheon, North Gyeongsang Province, in 1982 © Hyungwon Kang |

Following the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty signed in 1910, Koreans were left without a country to call their own. There was a systematic destruction of their traditions, values and language.

Suddenly bereft of a royal ruler, Koreans quickly espoused the concept of Korean independence and democracy, including civic participation.

On May 12, 1919, the Daegu District Court sentenced a Buddhist student, Yoon Hak-jo, 25, and nine defendants to 10 months in jail for leading a crowd to call for Korean independence on March 30 of that year at an open market in Daegu, where some 3,000 had gathered.

The 10 defendants were from Bohyeonsa, a Buddhist temple that was a satellite temple of Donghwasa in Daegu.

The March 1 Independence Movement in 1919, which was launched in the capital city of Seoul, spread like wildfire to other Korean cities and villages as well as among Koreans abroad within weeks and days.

A couple of world events led up to the March 1 independence movement against the Japanese colonizers.

Koreans were motivated by US President Woodrow Wilson’s Jan. 8, 1918 speech that articulated the concept of national self-determination and the “mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small nations alike.”

When Emperor Gojong died on Jan. 22, 1919, Koreans were heard through underground newspapers such as Gugminhoebo and Joseon Doglibsinmun that the emperor might have been poisoned by the Japanese.

|

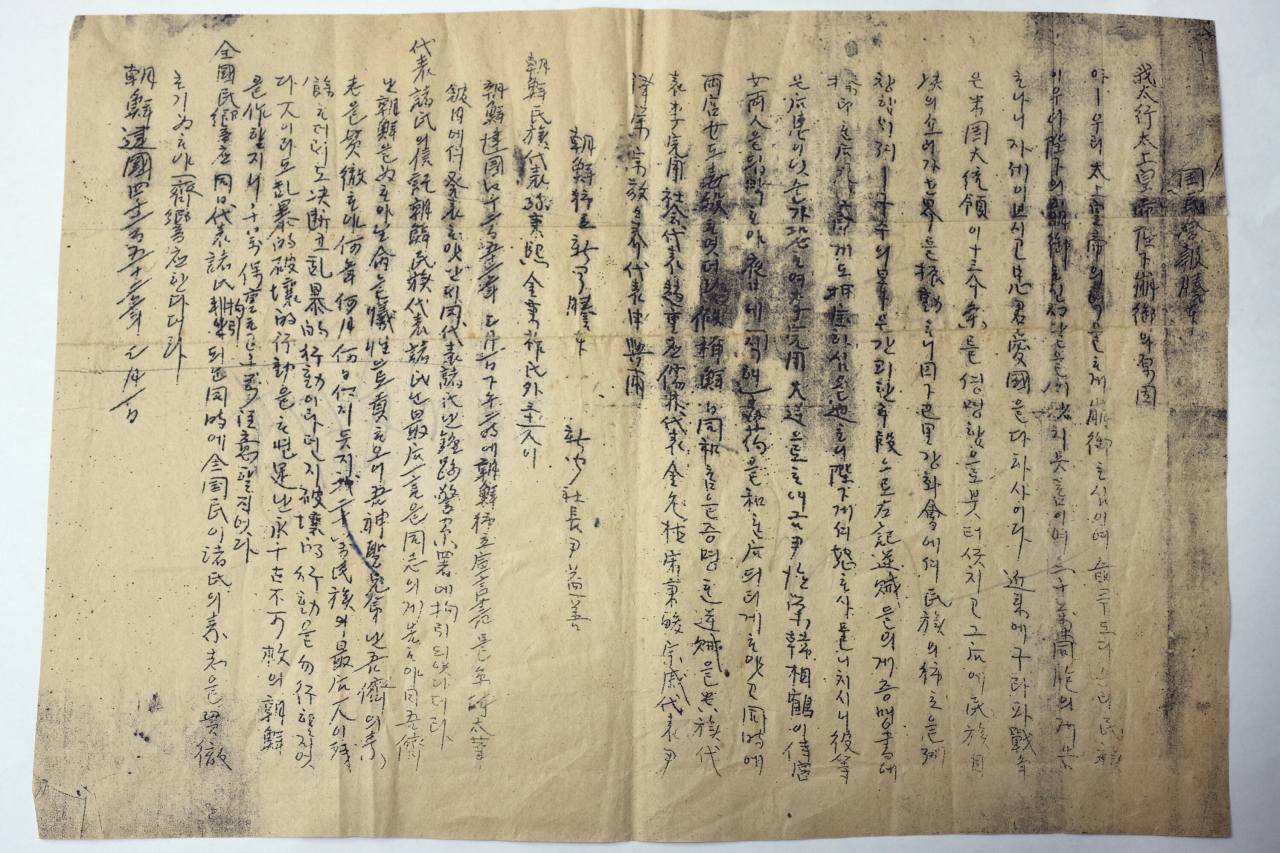

The only known mimeographed copy of two underground newspapers, Gugminhoebo and Joseon Doglibsinmun, are on a single sheet that dates from March 1919. © Hyungwon Kang |

The inaugural issue of Joseon Donglibsinmun, published March 1, 1919, was printed with metal type, but following confiscation of the movable metal printing type by the Japanese colonial government, subsequent issues were handwritten and printed by mimeograph.

Korean Americans in Los Angeles, who already had the Korean National Association handling their consular functions working with the US State Department, held rallies calling for Korean independence, as did Koreans in the Republic of China territory in the Manchurian region and Koreans in the Vladivostok area in the east of Russia.

Within Korea, the Government-General of Korea, the Japanese colonial government reporting to Japan, kept a detailed count of 7,979 people killed, 15,961 people injured and 46,948 people arrested during the Korean independence protests from March 1 through the end of May 1919.

The high number of people killed had to do with the Japanese colonial military shooting peaceful protesters with live ammunition, and many of the arrested not making it out alive from the detention facilities.

American and Canadian missionaries reported numerous cases of gross violations of human rights by the Japanese colonial police and military. There were brutal violations: Korean men, women and children being shot, beaten, bayoneted and burned with hot irons. Many, if not most, were tortured in prison.

“Some prisoners were tied to a rack or a cross, and their legs and buttocks were beaten with bamboo rods. Others were tortured with their flesh pinched out with pliers, bones dislocated, some were suffocated, and/or denied food and water. In most cases, the tortures were administered over several consecutive days so that the pain was drawn out,” according to Frank W. Schofield, a Canadian veterinarian and Protestant missionary who witnessed the Korean independence movement in 1919.

|

The Ven. Ji Woo, head of Bohyeonsa, walks past a mural in the temple celebrating the Buddhist monks who organized independence movements in Daegu. © Hyungwon Kang |

In May 1982, Jeon Yong-sul (1929-1988), owner of Yonghwasa, a small Buddhist temple in Yeongcheon, North Gyeongsang Province, had a dream.

“Buddha appeared in his dream and told him to go to Donghwasa in Daegu and receive beopdang, the main worship temple building,” said Jeon’s widow, Seo Bok-su, 87.

When Jeon went to Donghwasa, he was asked, “What took you so long to get here?”

A monk at Bohyeonsa in Daegu, a satellite temple of Donghwasa, also had a dream in which the Buddha told him to hand over the temple building when a man asking for it showed up.

It turned out that Bohyeonsa had grown out of the existing beopdang, or inner sanctuary, which was too small for the growing number of followers and was going to be replaced by a larger building.

“My husband, who left home unprepared, called me to tell me that we needed to get some money to pay for the dismantling and transport of the beopdang building. He also let me know that he needed to stay late and manage workers dismantling the hanok (traditional Korean building) structure. When my husband returned late that night, he definitely had a few drinks and was happy singing his way back to the temple. As a dancheong artist, he liked his gokju, (rice wine),” said Seo.

Years later, during a renovation at Yonghwasa, the only known copy of the first edition of the Joseon Doglibsinmun and another underground newspaper, Gugminhoebo, mimeographed on a single piece of paper was discovered tucked inside a table on which the Buddha’s statue was placed.

The Joseon Doglibsinmun issue dated March 1, 1919 reported that “after the declaration of independence, 33 signatories were taken into Jongno Police Station. The 20 million people of Korea must achieve the independence of Joseon through a nonviolent struggle.”

Meanwhile, Gugminhoebo reported that “Emperor Gojong was unjustly poisoned” and names nine collaborators with the Japanese.

Four years ago, 1919 court documents from the Daegu District Court revealed that Buddhist monks who were prosecuted and served time in jail for the March 30 independence movement had gathered at Bohyeonsa and planned the launch of the Daegu rally.

The Bohyeonsa beopdang building at Yonghwasa in Yeongcheon, about an hour from Daegu, may be returning to Daegu.

“When we can, we would like to bring the beopdang building back to Bohyeonsa, the location of the independence movement. Our temple is where the historical beopdang should be located to have a greater significance,” said the Ven. Ji Woo, head of Bohyeonsa. “We’ll have to build a new beopdang for Yonghwasa when we retrieve the historic hanok where our patriots led the independence movement.”

Meanwhile, a mural honoring the Buddhist monks who led the independence movement was installed on the side of Bohyeonsa in August 2019.

By Hyungwon Kang (hyungwonkang@gmail.com)

---

Korean American photojournalist and columnist Hyungwon Kang is currently documenting Korean history and culture in images and words for future generations. -- Ed.By Korea Herald (

khnews@heraldcorp.com)