On a Thursday morning exactly one week after “Cursed Bunny” -- her collection of 10 short stories translated by Anton Hur -- was announced among the works longlisted for the 2022 International Booker Prize, Chung told The Korea Herald that she was still in shock.

“Suddenly people are mentioning my name in the same sentence with Han Kang and Olga Tokarczuk, and I feel this is surreal,” Chung said.

Han is a Korean author who won the International Booker Prize in 2016 for “The Vegetarian,” translated by Deborah Smith. Tokarczuk is a Polish author who won the prize in 2018 for “Flights,” translated by Jennifer Croft.

Chung’s Booker nomination is the latest and the most high-profile addition to her list of literary accomplishments. She has written three novels and three collections of short stories.

|

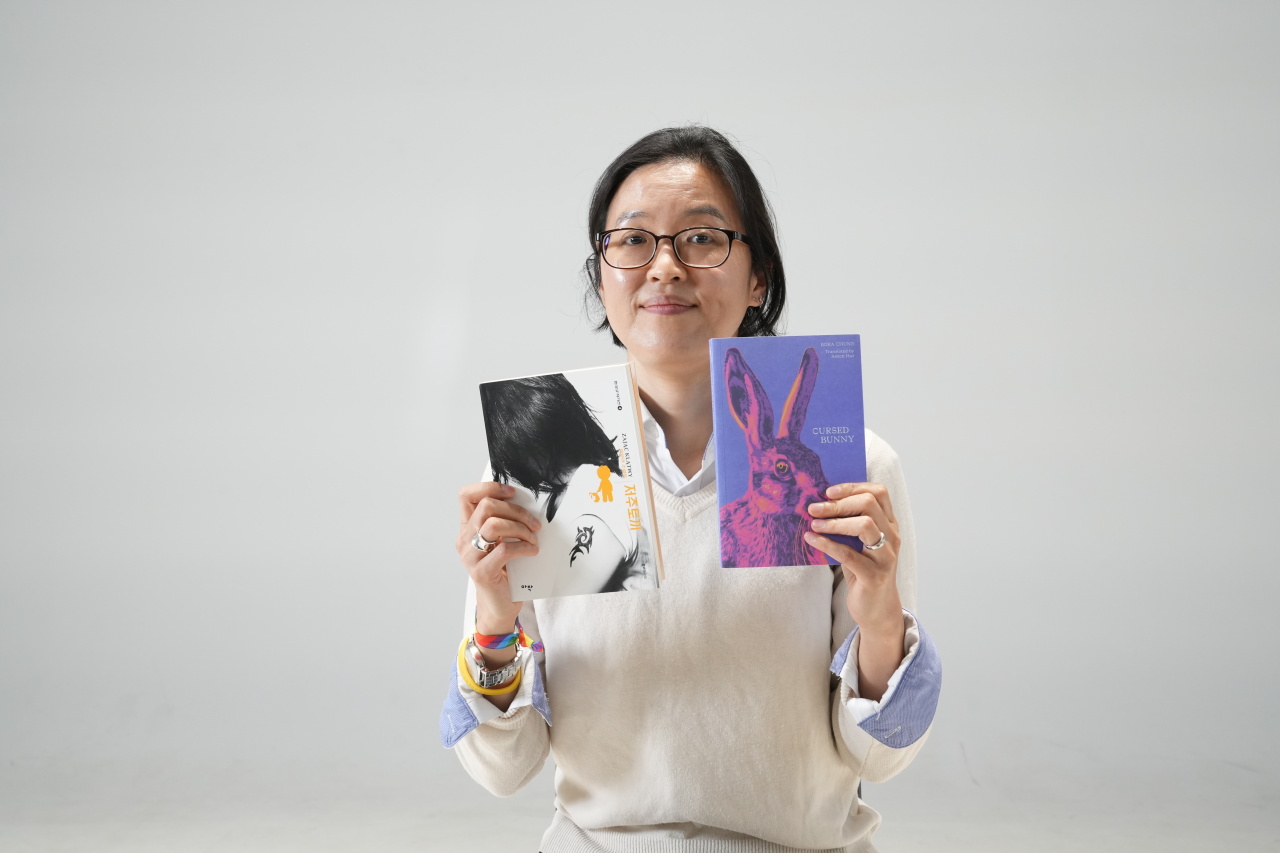

Bora Chung, author “Cursed Bunny,” holds the translated book and the original Korean book. (Kim Si-yeon/The Korea Herald) |

The 10 short stories in “Cursed Bunny” defy thematic or genre classification - spanning magical realism, horror and science fiction. Asked what it is about the horrors and cruelties of patriarchy and capitalism that fascinates her, Chung said that she was ultimately writing to make sense of the dark and confusing world.

“Something that is unexplained and unexplainable and something that people should not dare to explain with their very small knowledge of the universe -- those themes have constantly drawn me,” she said.

As a longtime social activist for the rights of oppressed groups -- notably laborers, women, and the LGBTQ community -- she highlighted how she writes to make sense of existing as a woman in modern Korean society.

“I don’t think I still understand the Korean society that I live in, and I’m constantly confused,” she said. “This entire world that I’m living in is a giant set of confusions, and I describe the world as I see it, so my stories come out as confusing and dark.

Born in Seoul in 1976, Chung cites “Samguk Yusa,” a collection of legends, folktales and historical accounts relating to the Silla, Goguryeo and Baekje kingdoms written in the 13th century by a monk, and the “unreal stories” of Silla, in particular, as among the inspirations for her wildly imaginative fiction.

“It’s the same in every culture. If you go back in time, people actually lived with the gods, and they believed that all the spirits and fairies inhabited the Earth with them,” she said. “That kind of worldview is still fascinating to me.”

She also admitted a love for Japanese and Korean urban legends, which reveal the limitations of sensory human experience.

“I think urban legends, myths and folktales constantly tell us that what you know is not all, and you shouldn’t be arrogant enough to think that what your five senses can sense is all there is to feel and perceive and think,” she said.

Russian fiction influences

Chung is also a translator of Russian and Polish literature into Korean. She holds a master‘s degree in Russian and East European area studies from Yale University and a Ph.D. in Slavic literature from Indiana University. She noted that Slavic -- especially Russian -- mythologies have also influenced her work.

Modern Russian women authors’ work is the focus of her translation efforts. She highlighted Lyudmila Petrushevskaya, Lyudmila Ulitskaya and Tatyana Tolstaya as three women postmodern authors at the forefront of Russian literature.

Chung pinpointed Russian detective crime writer Alexandra Marinina as a personal role model.

“She’s been writing for 30 years and her protagonist matures with her, so she has a 60-year-old woman detective who is dealing with her own personal life and attacking and criticizing major social problems in Russia,” Chung said. “She is amazing, and I want to be like her when I grow up.

|

"Cursed Bunny” author Bora Chung speaks during an interview held March 17 at The Korea Herald studio in Seoul. (Kim Si-yeon/The Korea Herald) |

Before the pandemic, she had been working on a novel about painkillers and investigating the nature of pain. But in the wake of the pandemic, she has been forced to re-examine her preconceptions.

“I had to reconceptualize everything because being sick now has a new meaning,” she said. “I just reconfirmed what I learned before the pandemic, that the more vulnerable classes -- the disabled, the elderly, the women, the children -- they are more susceptible to disease or economic crisis or both, and that we have to protect the more vulnerable class to protect ourselves.”

Asked where she sees herself in the next 5 or 10 years, Chung said she no longer thinks so far ahead into the future.

Laughing wryly, she said, “I think about next week, but not five years. I don’t do that. Not anymore.”

Video by The Korea Herald Books Podcast Team

Naomi Ng (ngnaomi@heraldcorp.com">ngnaomi@heraldcorp.com)

Beth Eunhee Hong (bethhong@heraldcorp.com)

Production

Kim Si-yeon (smk0105@heraldcorp.com)

Kim Su-hyeon (suhyeon0323@heraldcorp.com)

Lee Ji-min (19leejimin@heraldcorp.com)

By Beth Eunhee Hong (bethhong@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)