South Korea’s alternative education institutes are protesting the government’s push to introduce a mandatary registration system, claiming the move would extend the state’s grip on students who are fleeing regular schools and their rigid curriculum.

The Ministry of Education has announced it would conduct a special inspection of unauthorized alternative education facilities, a step that critics argue would pave the way for mandatory registration.

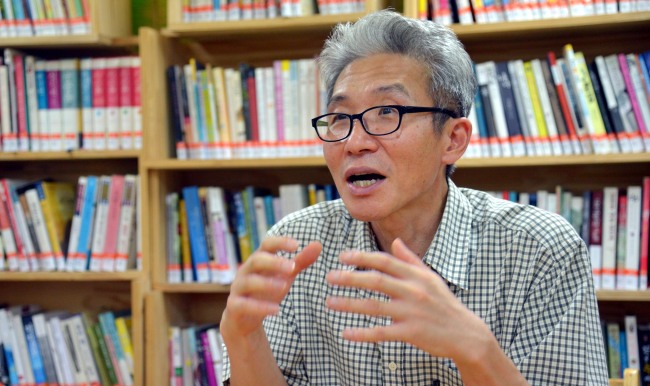

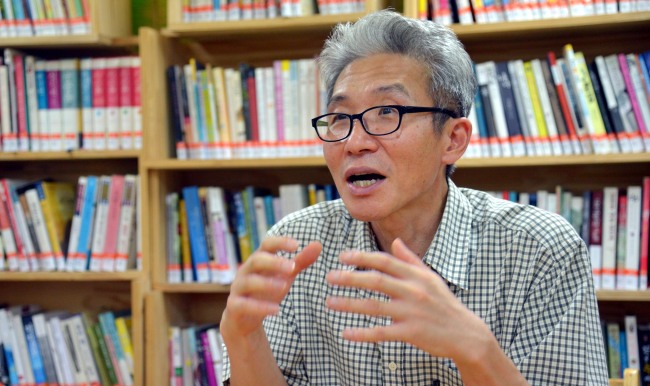

“The problem with the new measure is that it can lead to infringement of the schools’ autonomy. The plan specifies very strong control over the schools while promising very little support,” said Hyeon Byeon-ho, head of the People’s Solidarity of Alternative Education, in an interview with The Korea Herald. The PSAE is an association of 53 alternative schools nationwide.

Hyeon, also head of alternative school Mindle, said nontraditional schools need leeway to offer experimental education programs for students who feel that the conventional school system does not work.

“Simply put, alternative education is something that lets children be themselves. I think that is the essence of education,” he said.

The concept of alternative education first appeared in the late 19th century among European and American educators who believed education should cultivate the moral, emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual aspects in children.

In Korea, the movement started to gain momentum in the late 1990s, in response to criticism that the conventional education system only focused on delivering knowledge and preparing students for college entrance exams.

“Modern-day education itself is for the benefit of the country, not for students,” Hyeon said. “Its essence is the standardization of all things, including human. Teachers, curriculum and everything are standardized and made interchangeable.”

|

Hyeon Byeon-ho, head of the People’s Solidarity of Alternative Education. (Kim Myung-sub/The Korea Herald) |

In the book “In Defense of Childhood,” U.S. writer Chris Mercogliano discusses how children are “tamed” via school structures and risk-averse parents. Children’s adventurous nature, the spark that inspires them to explore, is smothered by control, the author claims.

Hyeon said Korea faces the same education problem, with outdated practices spawned by the military dictatorship still haunting the society. Far from promoting creative thinking, the iron-fisted regimes of the 1970s and 1980s strictly regulated what Koreans saw, read, heard and even thought.

According to Hyeon, education back then focused on fostering people who were obedient enough to follow the government’s command and control.

“The motto at Mindle is to help students become self-reliant and inspire them to help each other. That is actually the self-proclaimed goal of public education, although the reality is far from it,” he said.

Korea’s public education is dwarfed by the ever-expanding private market. The country’s private education spending, for instance, is among the highest in the world, due largely to the overheated competition to enter prestigious colleges, one of the key measures of success and social status here.

Such obsession over college entrance stems from parents’ fear of their children lagging behind in the competition with their peers, according to Hyeon.

“With an insufficient social security system, competition to avoid failing becomes even more intense. The distortion of education in Korea stems from the fear of falling behind,” he said. “They are terrified that they will fall short of the standards set by society.”

But as nonconventional schools strive toward alternative ways of education, concerns are being raised over the students’ well-being. Recent ministry data showed that some of unauthorized education facilities had substandard food services and buildings.

Also, while Korean law prohibits adult entertainment facilities from being built within 200 meters of schools, it does not apply to unauthorized institutes.

“The Education Ministry’s plan for the institutionalization of alternative schools is inevitable to some degree. With over 10,000 students enrolled in these alternative institutes, we cannot ignore our social imperatives, such as providing a safe environment for students,” Hyeon said.

He said the PSAE is proposing to the Education Ministry that unauthorized education institutes should be allowed to apply for registration or not, depending on their situations.

Hyeon said Korea needs institutions that remain outside of the regular education system to attempt novel methods of teaching, free from the influence of authorities.

By Yoon Min-sik (

minsikyoon@heraldcorp.com)