Following is the second in a series of articles on the future relations between China and two Koreas under next Chinese leader Xi Jinping ― Ed.

Despite ever-growing economic interdependence, South Korea and China remain discordant over history, territory, fishing, North Korean defectors and regional security issues.

With China ushering in a new leader this week, the two governments are expected to continue to try containing those volatile issues from flaring up, as stable bilateral ties are crucial to Beijing’s rise in income and power, and Seoul’s deterrence of nuclear-armed North Korea.

On Thursday, China’s Communist Party begins its biggest event in a decade, appointing a new crop of executives. Xi Jinping, the current vice president, is likely be named the new general secretary, replacing Hu Jintao to become the de facto leader of the world’s second largest economy. Xi is expected to succeed Hu as president next March.

The decennial power transfer is unlikely to bring a drastic change in the short-term to the 20-year relations between Seoul and Beijing, experts say.

Xi has been a key player among incumbent policymakers and his foremost challenge will be keeping its economic engine running in the face of domestic and global uncertainties.

Little in Xi’s record implies that he would veer the fledgling global powerhouse toward a starkly different course. Neither can he afford any sweeping changes abroad as he faces a triple whammy at home with signs of slowing growth, increasing middle-class assertiveness and mounting calls for political reforms, they say.

“(Xi) is part of a collective leadership being put in place because he supports the policies and approaches of the current leaders,” said Ralph Cossa, president of Pacific Forum CSIS, the Asia-Pacific arm of Center for Strategic and International Studies based in Honolulu.

“I envision no drastic changes or some sort of breakthrough for the relations between the two nations unless an emergency occurs such as one in North Korea. They will likely be making slow progress,” said Yoon Pyung-joong, a political philosophy professor at Hanshin University in Gyeonggi Province.

But experts warned Seoul may have to walk a fine line between the U.S. and China with their rivalries escalating over trade, currency and strategic supremacy in East Asia.

The Korea-China ties could also fall prey to a possible nationalist surge and expansionist push under the new generation of Chinese leadership.

|

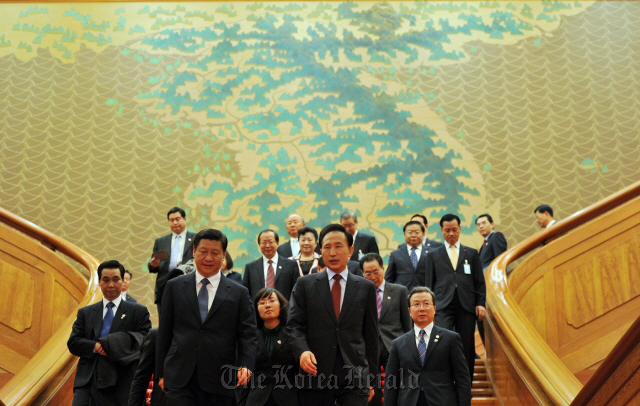

President Lee Myung-bak (first row, right) walks with Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping (first row, left) and other officials after a meeting at Cheong Wa Dae on Dec. 17, 2009. (Cheong Wa Dae) |

Bilateral ties

In the Korea Peninsula policy, soon-to-be leader Xi is widely expected to hold on to the current line of cooperating with South Korea on economy and North Korean nuclear programs.

Seoul and Beijing established diplomatic relations in 1992 and upgraded their ties over time to a “strategic cooperative partnership” in 2008 establishing a set of high-level dialogue channels that have helped untangle knotty problems that often posed threats to bilateral ties.

For Korea, the rising global power is already one of its biggest trade, tourism and investment partners. For China, firmer ties with Seoul are vital in stabilizing the region, keeping the U.S. and Japan in check and securing industrial technologies.

More broadly, Xi’s foreign policy will likely have two pillars ― putting relations with Washington on track while maintaining its initiative in the regional diplomacy prone to high-stake disputes.

But nationalism and a show of force could be a bone of contention if the new leadership attempts to divert public attention overseas while they consolidate power in the face of already toll challenges at home.

Its economy is cooling off after a decade of breakneck growth. Bureaucrats’ corruption is rampant from top to bottom. Popular protests, propelled by a rising middle class, erupt one after another calling for a transparent government and fair society.

“China will probably find it hard to attempt at a far-reaching transition in external matters at a time when they are engrossed in taking care of what’s on their plate,” Yoon said.

“Irrespective of the leadership change, it’s a common strategy for an authoritarian, nondemocratic state to fuel nationalism inside as an exit to domestic instability.“

Diplomatic thorns

Territorial claims, intertwined with two millennia of checkered history shared by the two countries, has been a perennial source of tension.

Spats have turned intense and frequent lately as China increasingly asserts cultural hegemony, or Sinocentrism, in line with its ascendency in the global economy and politics.

A recent series of flare-ups over remote islands in nearby waters has thrust the fast-emerging military powerhouse into a nationalist bandwagon, prompting concerns over a possible resurgence of the ancient notion.

“The ongoing territorial rows, together with the Chinese society’s nationalist attribute, will only make Xi more assertive especially when he ought to show his leadership and needs military backing,” said Choi Kang, a professor at the Korea National Diplomatic Academy in Seoul.

“He may roll out his own recipe for foreign affairs after the power transition ends but the current trend will likely hold out at least till 2014.”

Tension reached a new high last week after Chinese patrol boats confronted Japanese vessels near the archipelago in the East China Sea, called Senkaku in Japan and Diaoyu in China.

China has also insisted on jurisdiction over Ieodo, Korea’s southernmost island in the intersection of the two countries’ exclusive economic zones. Beijing is mired in a separate territorial brawl in the South China Sea with the Philippines.

On the history front, China regards the old Korean kingdom of Goguryeo (B.C. 37 to A.D. 668), located across what is now northern Korea and southern Manchuria, as its former vassal. Under the so-called Northeast Project, Beijing has claimed its past sovereignty via state media, official reports and cultural sites.

Escalating diplomatic friction has been lending impetus to calls for a sharp expansion in Korea’s naval force and greater cooperation with its longstanding ally ― the United States.

“While its neighbors seek U.S. help in resolving the territorial problems, Beijing over the long-term will strive not to slide into a two-way showdown against Washington,” said Kang Jun-young, a Chinese studies professor at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Seoul.

“But from the Korean standpoint, there’s a considerable possibility that we would often witness China’s show of force when it comes to relatively trivial and less risky matters, including the Senkakus, to stimulate nationalism and take the initiative at least in Asia.”

|

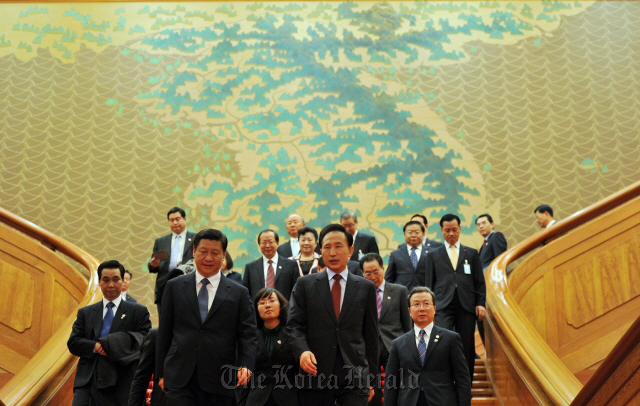

President Lee Myung-bak (right) shakes hands with Chinese Vice President Xi Jinping before a meeting at Cheong Wa Dae on Dec. 17, 2009. (Cheong Wa Dae) |

North Korea

Domestic issues aside, relations between Seoul and Beijing will more likely hinge on the nova-like situation surrounding the peninsula after elections in South Korea, the U.S. and Japan ― all of them members of a six-nation forum on denuclearization in the North.

The 18th Party Congress comes only two days after the U.S. presidential election. Seoul’s Dec. 19 vote will bring in a president with a more flexible and inclusive approach toward Pyongyang than that of Lee Myung-bak, the conservative incumbent.

“Beijing hopes that Seoul will dilute its ties with the U.S., and instead work more closely with China to promote a better outcome on the peninsula,” said Bonnie Glaser, a China specialist at the Washington-based CSIS, via email.

“At the same time, China will maintain close political and economic ties with Pyongyang. … The Chinese need to be positioned to influence both countries so it can protect Chinese interests in any future scenario.”

Still the outlook for six-party talks appears dim amid an increasingly intense Sino-U.S. rivalry and the North’s persistent saber-rattling.

Policy cooperation could become even tougher if challenger Mitt Romney succeeds in taking over the White House from President Barack Obama. The Republican is set to deal toughly with the “rogue nation” North Korea and has vowed to label China as a “currency manipulator.”

Japan is also widely expected to pick a more hawkish prime minister in general elections later this year.

Meanwhile, Beijing remains the cash-strapped Pyongyang’s supreme ally and donor. It has been blamed for repatriating North Korean defectors despite risks of torture, detention in prison camps or even death.

In a December 2009 interview with Korean and Japanese media, Xi stressed China’s position that the peninsula “should be denuclearized, the issue should be resolved through dialogue and peaceful ways, and the peace and stability of the peninsula and Northeast Asia should be maintained.”

Social issues

Other tricky issues include rampant poaching by Chinese fishermen and a rise in heinous crimes and financial frauds by Chinese nationals, mostly ethnic Koreans.

In recent years, the West Sea has turned into a scene of clashes between Chinese fishing vessels and Korean patrol boats.

Anti-China rallies relayed here after a Chinese skipper stabbed to death a Korean Coast Guard officer during a December raid on his boat. Another dozens have been injured by sailors wielding deadly weapons.

Furthering tension, human rights activist Kim Young-hwan early this year exposed systematic torture and other abuse by Chinese investigators during his near four-month detention. Beijing denied the allegations.

Public anxiety remains high since a Chinese national of Korean descent brutally murdered a young woman in April in Suwon, Gyeonggi Province.

The phone fraud-inflicted damage between 2008 and 2010 topped 200 billion won ($183 million), prosecution data shows. Most scammers are traced to networks in China who masquerade as acquaintances, police or bank officials to siphon off bank accounts.

Experts say the two countries should not pair their ties and issues emerged from the sidelines, equating all diplomatic relations to a sine curve with ceaseless ups and downs. Seoul has sought an amicable settlement of sensitive issues with its top trade partner and the world power.

“After all, the two governments should keep up dialogue and establish standards for dealing with certain matters,” Kang of HUFS added.

“In terms of criminal cases, for example, they should pursue cooperation in investigation and jurisdiction to strictly handle serious crimes. That way, they can facilitate extradition and information sharing,”

By Shin Hyon-hee (

heeshin@heraldcorp.com)