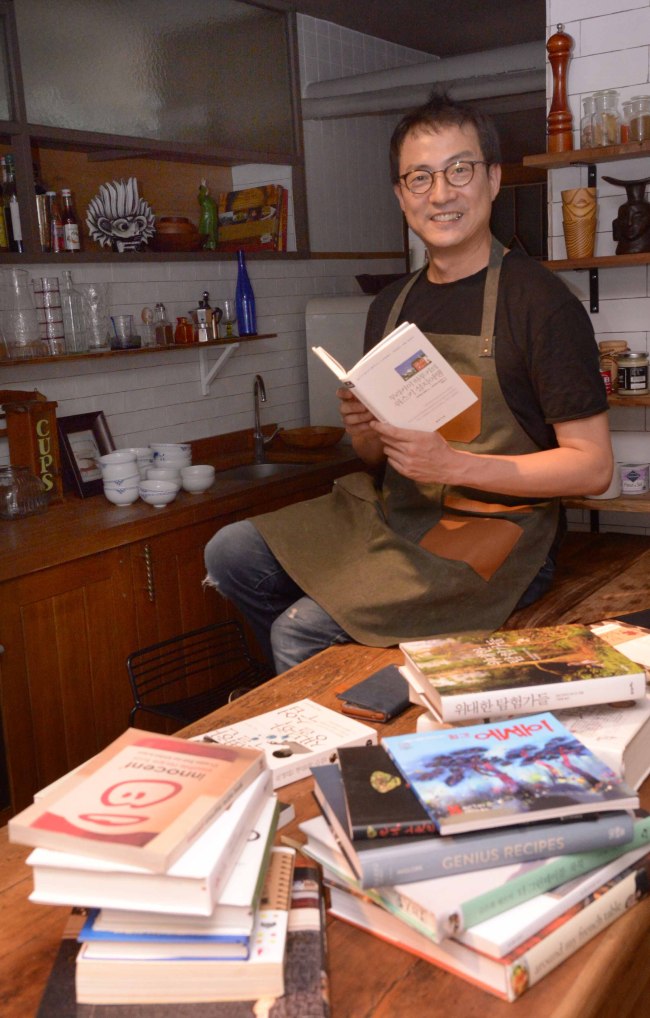

Taking a seat in his cooking studio in Sangsu-dong, Seoul producer Lee Wook-jung was doing little to dispel his globetrotting image.

“I just got back from a week in Kyoto,” he said.

The KBS producer, best known for his Peabody Award-winning 2008 series “Noodle Road,” has spent a considerable amount of the year outside Korea, scoping out locations and interview subjects for his documentaries.

With an academic background in cultural anthropology, culinary training from Le Cordon Bleu London and the technical skills of a producer, Lee has been able to create works that simultaneously discuss the technique of cooking and the cultural significance of food and its preparations to different cultures.

|

Lee Wook-jung (Chung Hee-cho/The Korea Herald) |

He said that his interest in food began when he was very young.

“My family had a pretty cosmopolitan background,” he said. “My father was born and raised in China, and my mother was born in Japan.”

Lee grew up eating Chinese, Japanese and Korean cuisine, and learned to develop an eye for quality food thanks to his gourmet father.

“He didn’t eat a lot, but he liked expensive, fine foods,” he said. “If we were at a Chinese restaurant, it was always course meals. Money was no object with food. That’s why we were poor,” he joked.

Lee’s mother was also devoted to food, preparing abundant and lavish meals three times a day. Lee says it wasn’t until he became an adult that he realized most people didn‘t normally eat that way.

“Now, I’m a storyteller who specializes in food. Those experiences were instrumental to bringing me here.”

His interest in food was sparked again when he was doing field work for his master’s degree in cultural anthropology. His thesis was about the symbolic resistance of Muslim Bangladeshis working illegally in Korea -- how they coped with the discrimination they faced in everyday life using cultural mechanisms. One of those mechanisms was the concept of halal, or permitted foods, which forbids dog meat.

“Koreans were above them socioeconomically, but in (the workers’) minds Koreans were dirty because they ate polluted foods.”

“(That experience) showed me how important food was in defining who we are in contrast to others. It’s more than just nutrition.”

Lee said that this significance of food was relatively unexplored in Korean TV.

“Food is normally considered a very light topic in Korean TV documentaries, and most of them were about only Korean food,” he said. “I wanted to do something that compared cultures, outside the frame of Korean food.”

Lee also wanted to break away from the deep-rooted nationalism inherent in documentaries about Korean food. “Our doenjang (bean paste) is the best. China and Japan are doing it wrong. Kimchi is the best. -- It’s nationalistic, and it’s a perspective that can’t be sold to viewers overseas.”

According to Lee, the act of properly examining the food of other cultures was actually a better way of determining the strengths of Korean cuisine.

“Take kimchi for example. Korea is not the only country with the culture of salting vegetables and fermenting them. When you know that, you see the value of kimchi,” he said. “Everyone’s discovered that vegetables can be kept longer and taste better when they’re salted. But kimchi adds more layers to that, which is why it’s garnering interest around the world.”

“You have to be able to see the advantages other cuisines have in order to see the strengths of Korean cuisine.”

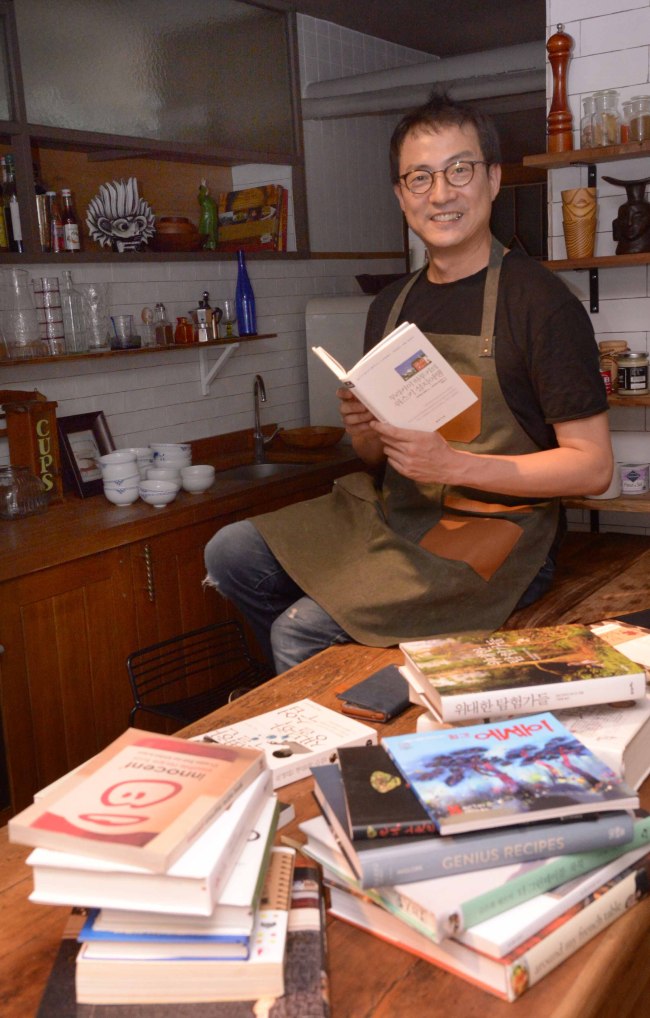

|

Lee Wook-jung (Chung Hee-cho/The Korea Herald) |

That goal led him to create the seven-part documentary series “Noodle Road,” which brought him a prestigious Peabody Award in 2009 for the episode “Connecting Asia’s Kitchens,” followed by this year’s eight-part documentary “Food Odyssey.” For him, food was a way of understanding all of humanity.

“Food is not just about what you taste at the tip of your tongue. The symbols, stories and discourse surrounding food create culture,” he said.

“When we talk about the globalization of American food, it includes a certain lifestyle. Japanese food is also associated with a lifestyle and a philosophy. That’s why, all over the world, the most expensive restaurants serve Japanese cuisine. People think of it as an immense cultural experience.”

He says that the sudden proliferation of content about food -- whether pictures of food on social media or TV shows about food and cooking -- reflected an understanding of this significance of food.

“It’s actually strange that it took this long. Eating is one of mankind’s most basic desires,” he said. “We’ve been repressed all this time. The chains are coming off. It’s a human rights declaration!” he proclaimed.

“We’re shouting that we want to eat what we want to eat. This is the beginning. Now, we have to translate it into culture, to know the stories behind the food. That will make it even better.”

Lee has just wrapped up a daily 62-part series of short 10-minute shows called “Wook’s Food Odyssey,” where he personally appeared on camera to share recipes from around the world and the stories behind them. Now, he is working on a new project.

“It’s ‘Food Odyssey Season 2,’” he said. “It’ll be a city adventure. Every episode will explore a different city by experiencing local life for a week, having three meals a day.”

Through food, Lee said he wants to talk about each city’s history, everyday life and the environmental, cultural and political challenges faced by each community.

“It’s not just about Paris and Tokyo. I’m actually looking for hidden gems, cities with wonderful hidden histories of food.”

According to Lee, his team welcomes suggestions for filming locations at

foodplanet@kbs.co.kr.

By Won Ho-jung (

hjwon@heraldcorp.com)