What did the Japanese look like in the eyes of Koreans in the colonial period (1910-1945)? The images of high-handed military police and officers armed with swords, elementary school teachers who shout “Banzai!” (Long live the emperor!), the coercive landowners who lorded over the tenants and prosecutors, judges and other officers of the Japanese Government-General of Korea could come to mind. From their point of view, the Japanese were invaders and colonialists, or in other words, merciless rulers. However, there were rare exceptions. Some Japanese sympathized with Koreans and opposed their country’s colonization of Korea and the former’s brutal rule over the latter. The most famous example is lawyer Tatsuji Fuse (1880-1935). In 2004, the Korean government awarded him the Aejok Jang Order of Merit for National Foundation. He is the only Japanese person to have received the honor.

Who is Tatsuji Fuse?

|

Tatsuji Fuse |

Fuse was born to a farming family in Hebitamura in Japan’s Miyage Prefecture. Graduating from Jinjou Elementary School, he studied classical Chinese in the village school and learned of Mozi’s “impartial caring” or “universal love” and became highly interested in Christianity, later being baptized into the Greek Orthodox Church. A participant in social activism, and sympathizing with the Tolstoyan movement of Christianity, Fuse remained a pacifist throughout his entire life. He came to Tokyo in 1889 and first entered Tokyo College (now Waseda University), but transferred to Meiji Law School (now Meiji University) and graduated in 1902. That same year, he passed the bar exam and was made a probationary judicial officer. The following April, he became probationary prosecutor of Utsunomiya District Court, but resigned that August over an indictment for attempted murder made against a woman who attempted suicide together with her daughter. He could not prosecute what he felt was the social pathological phenomenon of a wife being accused when she was the victim of neglect by her husband. Fuse then began to practice law in Tokyo from 1903, beginning to focus on Tolstoyism before in 1920 he declared that he would only defend laborers, farmers and the helpless in society (“Confession of Self-Revolution, 1920”). He resolved to stay true to his motto of “Live with the people and die for the people” for the rest of his life as a lawyer.

A fateful encounter with Korea

The fates of Fuse and Korea can be said to have been intertwined since 1919. In February that year, around 60 Zainichi Koreans and Korean students abroad were indicted for the Feb. 8 Declaration of Korean Independence. Fuse was the appellate court defense attorney for Choi Pal-yong, Baek Kwan-su and seven others charged with violating publication laws. Although all nine were found guilty, Fuse gained the trust of Koreans for defending them pro bono. Afterwards, Fuse became actively involved in various cases defending Koreans.

Fuse became interested in Korea thanks to the Feb. 8 Declaration of Independence and March 1 Independence Movement. In 1921, he organized the Liberty Law Group, which defended the proletariat party movement for laborers and farmers, the Burakumin liberation movement and Korean and Taiwanese people.

At 11:50 a.m. on Sept. 1, 1923, a magnitude-7.9 earthquake broke out in Tokyo, the center of the Kanto region. As lanterns and candles were being lit in preparation for lunch, the aftershocks from the quake sparked huge fires. The Kanto region from Tokyo to Yokohama was destroyed, suffering great damage. The missing and dead numbered 14,000 and 3.4 million people lost their homes and livelihoods.

Amid the chaos, martial law was in effect and baseless rumors ran rampant in an atmosphere of social instability: “The Koreans incited riots.” “The Koreans committed arson.” “The Koreans poisoned wells.”

Groundless rumors spread through the police emergency communication networks and the civil militia and police massacred Koreans, and even Chinese and Japanese they mistook for Koreans.

During the massacre that followed the Great Kanto Earthquake, approximately 6,700 Koreans and 700 Chinese were killed by Japanese military, police and civilians. About 10 others, including the anarchist Osugi Sakae and labor movement leaders, were also murdered by the regular and military police.

Fuse protested the massacre of Koreans and sought to open an investigation into it. He also tried to hold a memorial service for the dead, which was suppressed. Shortly afterward, the anarchist Park Yeol and his wife Kaneko Fumiko were arrested for high treason.

While covering up the massive killings of Koreans after the earthquake, the Japanese colonial government arrested those suspected of harboring socialist ideology that opposed the emperor under the pretext that they needed to be put into custody for their own protection.

Park and Kaneko were charged with high treason in the pretrial and sentenced to death by the Japanese Supreme Court on March 25, 1926, which was then commuted to life imprisonment on April 5. Kaneko committed suicide on July 23, 1926 in the Utsunomiya prison. Fuse dedicated his all to the case. It was Fuse who procured Kaneko’s body and sent it to her family.

Walking the path of struggle along with Koreans

|

This still from a TV documentary on Fuse Tatsuji’s life shows the group, consisting of Korean-Japanese and Korean students studying abroad, behind the Feb. 8, 1919 Declaration of Korean Independence. Fuse defended them in court. |

Fuse was not only active in Japan, but walked along with Koreans on their path of struggle by lecturing and lawyering in Korea. Inevitably his activism encountered many obstacles under the Japanese Government-General of Korea’s thorough surveillance and suppression.

In July 1923, Fuse visited Korea for the first time to participate in the “Summer Lecture Tour” sponsored by the Dong-a Ilbo newspaper and supervised by the North Star Society, a group of students studying abroad. Fuse stated that “My coming to Korea … was not to view its landscape, for my main goal was to connect with the feelings of the Korean people.”

Fuse started his lecture tour on Aug. 1 in Seoul and lectured about 10 times in each region in the south until Aug. 12, causing a great sensation. He also agreed to defend the patriot Kim Shi-hyeon, a member of the patriotic Uiyeoldan group, in the Seoul District Court. Although defense was only provided through documentation, Fuse made clear his intent to support Korea in court.

In 1926, he visited Korea for a second time with the goal of supporting the Korean farmers’ movement to resolve a land dispute in a village of Gungsam, Naju County in South Jeolla Province, with Japan’s Oriental Development Company. The farmers requested Fuse’s help in recovering their land rights after the Koreans’ land was forcibly transferred to the ODC.

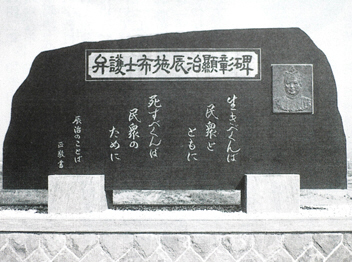

In fulfilling the request, Fuse stayed in Korea from March 2-11, 1926, distributing inquiry forms and conducting on-site surveys and separate investigations despite obstruction from the police. Frightened that Koreans all around the country would fight back against the taking of their land, the Government-General forced ODC to come to an agreement with the Korean farmers quickly. In present-day Gungsam, a commemorative memorial of this fight still stands with the record of Fuse’s efforts.

Fuse visited Korea twice more to support Korean independence and social reform and to defend Koreans in court. In September 1927, he defended Park Heon-yeong and other members of the Korean Communist Party. In October, he visited Korea yet again to fight the case and stated: “In reality, the Korean Communist Party’s case is a kind of resistance against the coercion of the Government-General.”

Looking toward future Korean-Japanese relations

|

Tatsuji Fuse’s gravestone |

Fuse was suppressed for his defense of Koreans even within Japan. In 1932, his bar license was revoked. The next year the Japanese Labor and Farmers’ Lawyer Association, with which Fuse was affiliated was swept up in mass arrests. Fuse was charged with violating the Maintenance of Public Order Act in 1939 by the Supreme Court, sentenced to imprisonment and the loss of his bar license. For nearly a year, he was kept in custody at the Chiba Prison. His third son, Morio, was also arrested for violating the Maintenance of Public Order Act in 1944 and died in prison.

Immediately after August 1945, when Japan surrendered unconditionally to the Allies, ending World War II and the 35-year colonial rule of Korea, Fuse became active again. In 1946, with the drafting of the Korean Constitution, Fuse hoped to again contribute, even if only a little, to Korea. Recovering his bar license, he actively defended the rights of Zainichi Koreans involved in the May Day Incident, Koreans arrested for making makgeolli for their livelihoods and for the struggle in establishing education for Zainichi Koreans in Hanshin in 1948. It is no exaggeration that until his death at 72 in 1953, Fuse defended the Koreans in nearly every Japanese case they were involved in.

At his funeral, many Koreans attended as funeral commissioners. Tatsuji Fuse, who had viewed the Koreans as equals with the Japanese and fought and sympathized in their struggles, has been recognized as a friend and comrade of the Korean people.

By Seo Min-kyo, Researcher, Korea Institute of Foreign Relations, Dongguk University

In Korea’s turbulent path toward independence and nation building, there were foreign nationals who stood steadfastly by the Korean people, although their contributions have been largely overshadowed by those of Korean patriots. The Korea Herald, in partnership with the Independence Hall of Korea, will publish a series of articles shedding light on these foreigners, their life and legacies here. The following is the second installment. ― Ed.