On May 21, 1886, in the port city of San Francisco, 23-year-old Homer Bezaleel Hulbert and the husband and wife pair Delzell A. Bunker and George W. Gilmore were about to embark on a journey to the unknown land of Joseon. After launching on June 1 and sailing for 18 days, their vessel arrived in Yokohama, Japan. Moving to Nagasaki, they took another vessel to their final destination of Jemulpo, Incheon. They sped down the Seoul-Incheon road, rode a small ferry across the Hangang River and then entered the capital’s Namdaemun Gate. It was July 4, the American Independence Day when they finally arrived in Seoul.

The young American was to be an English instructor at the Royal English School, established by the Joseon Dynasty which ruled the Korean Peninsula at that time, with the intent of training officials for diplomatic affairs.

|

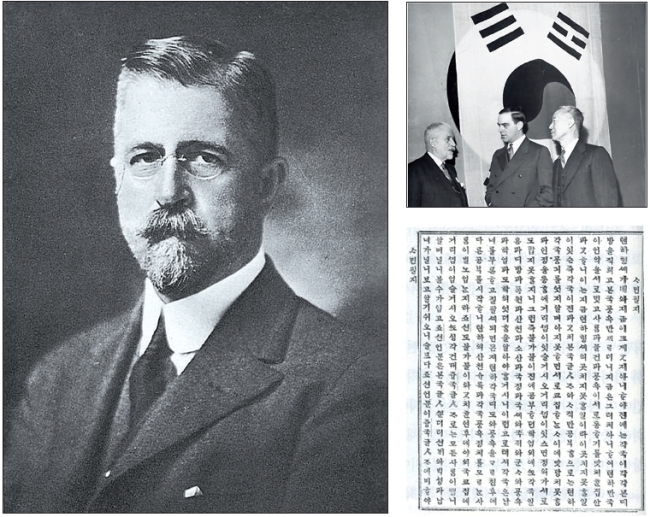

(Clockwise from top) Homer Bezaleel Hulbert (1863-1949). Hulbert (center) and Syngman Rhee (right), participating in the 1942 Korea Freedom Convention in Washington, D.C. “Salminpilji,” the first textbook published in Hangeul in 1889, means “Knowledge Required for All.” (Independence Hall of Korea) |

Born in 1863 in the city of New Haven, Vermont to parents who were the descendants of Puritans, Hulbert was a man of devout faith, having graduated from Dartmouth College and studied theology at the Union Theological Seminary.

As an instructor at the school, he was passionate about teaching and, at the same time, was enormously interested in the Korean language and history. This passion led him to gaining conversational fluency in Korean. Communicating with his students in Korean, he was able to stimulate their curiosity and open their eyes to international affairs. The students’ desire to learn was proportional to their enjoyment of their relationship with Hulbert, with King Gojong and the elites participating in classes and expressing great interest in modern education. Hulbert spent a great deal of time on correcting English pronunciation, but also had his students recite conversational lines because, after all, there is no royal road to learning.

First Hangeul textbook

Using his experiences in education as a base, Hulbert published and distributed the first Hangeul textbook, “Saminpilji,” or “Knowledge Necessary for All” in 1889, merely three years after arriving in Joseon.

The first edition published in 1892 had 2,000 copies. The table of contents, followed by the foreword, covered the nations of five continents and their geography, nature, government structure, customs, religions, industry, education, military, political systems and social welfare.

“If every country only studies their own letters and histories, one would not know the customs of all the countries under heaven, which would be improper for mutual interaction and inhibit empathy. If there is inhibition, mutual understanding and sympathy would be lacking and one must learn the names of other countries, localities, breadth, nature, boundaries, national taxes, commodities, military, customs, learning and ethics in addition to one’s previous studies to prevent this. … After doing this, inevitably Joseon will also have no constraints on its diplomatic contact with other nations,” the foreword reads.

|

Directors of the U.S.-Korea Conference gathered in Ashland, Ohio, in 1942, in a campaign to gain the approval of the Korean Provisional Government from the U.S. |

Also, Hulbert actively promoted Korean culture and Hangeul to the outside world, writing articles in his spare time for publication in U.S. newspapers and magazines. When his contract expired in 1891, he returned to the States, only to come back to Korea two years later as a Methodist missionary.

Foothold for modern education

In May 1897, Hulbert signed a contract of employment with the government as the director of the Hanseong School of Education. Focusing on basic education rather than teaching skills, he submitted a “Recommendation to Reform Schools” through the U.S. envoy to the Korean foreign minister. He believed that under current conditions, the operation of schools could not be properly conducted. Thus if the operation of schools failed, not only would his reputation be tarnished, but modern education in Korea would not be developed at all.

In 1900, he took a teaching job at the Imperial Middle School. While teaching, he again focused on establishing a system for textbooks. From 1906 to 1908, he published a total of 15 textbooks, at a combined cost of $15,000. Emphasizing the importance of history education, he stated, “Those who do not know their country’s history are no different from beasts, unable to compete with foreign countries, and even if they did, only lose.” Oh Seong-gun’s “The History of Korea” (1908) was coauthored by Hulbert.

He also did not hesitate in aiding young people who wanted to study abroad. Among them was Cha Mirisa, who crossed over to the U.S. via Shanghai in 1905 and returned in 1917 to become one of the country’s leaders in female education. Hulbert exerted all his energy in sending many young people abroad.

Other cultural contributions

In 1893, he was director of the Trilingual Press and Baejae School. When Korea’s first civic movement organization, the Independence Club, was established, Hulbert helped Philip Jaisohn published the Independent to report on the international situation. In 1901, Hulbert became editor-in-chief of the Korea Review and the Korean Repository, which were channels to the outside world that promoted news, academics and public opinion of Korea.

Hulbert left his mark on traditional culture by transcribing “Arirang” in 1896, the song most emblematic of Korean sentiment. His article, “Korea’s Vocal Music” scored “Arirang,” the “Roasted Chestnuts Song” and other songs in Western style-music sheets for the first time. Hulbert defined “Arirang” by saying: “‘Arirang’ is like rice to the Koreans.”

His relentless work on Korean history was condensed into “The History of Korea” and “The Passing of Korea” in which he asserted, “Takeshima is originally Joseon territory,” referring to Dokdo Island, whose territorial rights remain a point of contention with Japan.

|

Hulbert’s firstborn daughter (left), older son (center) and younger son (right), with a Korean folding screen in the background. |

A comprehensive masterpiece on Korea’s history, culture, traditions, industry and society published in 1906 in London, “The Passing of Korea” was written in order to raise awareness of the demise of the Daehan Empire, which followed the Joseon Dynasty, lasting from 1897 to 1910. In the book, which included photographs of daily life and historic sites, Hulbert did not hesitate to vociferously criticize the U.S., which was the first to withdraw its legation to Korea after the forced signing of the Eulsa Protectorate Treaty of 1905 between Korea and Japan, which led to Japan’s annexation of Korea.

Promoting Korean independence

“The Passing of Korea” is also an important source for understanding the Chunsaengmun Incident of the time, and its writing originated from Hulbert’s intent to advocate Korean independence to the world along with Korean history and culture. Hulbert was appointed a special delegate by Emperor Gojong and traveled to the U.S. to appeal to the international community concerning the illegality of Japan’s takeover of Korea and the injustice of the 1905 treaty.

In the Second International Peace Conference held in The Hague in 1907, he condemned Japanese imperialism as a Korean delegate, leaving a significant mark in the history of the Korean independence movement. He also traveled to Shanghai on a special mission to secure a privy purse for the king. After his exile from Korea by the Japanese ruler, he continued to appeal for the legitimacy of Korean independence along with Philip Jaisohn and Syngman Rhee. Through lecture tours and newspaper articles, he continued to advocate for Korean independence, criticizing U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt’s Korea policy.

On Aug. 5, 1949, some 40 years after his deportation, Hulbert finally stepped on Korean soil again, but only one week later, he passed away due to the fatigue of travel. He was 86.

“I would rather be buried in Korea than in Westminster Abbey,” Hulbert said in his will.

His remains were buried in a foreigners cemetery overlooking the Han River. In 1950, he was awarded the Order of Merit of National Foundation by the Korean government, and on Hangeul Day last year, he received the Gold Crown Order of Cultural Merit.

By By Kim Hyong-mok, Research fellow, Independence Hall of Korea

In Korea’s turbulent path toward independence and nation bulding, there were foreigners who stood steadfastly by Korean people, although their contributions have been largely overshadowed by those of Korean patriots.

The Korea Herald, in partnership with the Independence Hall of Korea, will publish a series of articles shedding light on these foreigners, their life and legacies here. The following is the first installment. ― Ed.