“There’s no evidence at this stage that the great books in our culture can be produced through the Internet right now,” says best-selling writer James Patterson. “If the equivalent of ‘Ulysses’ came along, out it would go on the Internet, it would get like about 12 Fs in a row ― ‘I couldn’t get through the first page,’ ‘Couldn’t get through the first chapter,’ F-F-F-F-F, and ‘Ulysses’ would disappear.”

Patterson is not known for Joycean prose ― he’s known for propulsive Alex Cross thrillers ― but his prominence as one of the world’s biggest-selling authors has made him a prophet with a platform. He’s on a crusade to make books matter ― to, as his hashtag says, #saveourbooks.

In addition to publishing 10 books a year, his recent endeavors have included a petition campaign to get President Obama to demonstrate a love of reading, giving $1 million to independent bookstores, funding teacher scholarships, making a documentary about disadvantaged neighborhoods, partnering with the Library of Congress and tussling with Amazon.

“I’m just stepping up, trying to make some noise, and get others to step up,” he says self-deprecatingly, talking by phone from his home in Palm Beach, Florida. “With the Amazon thing, I could draw attention to the effect it’s having on a lot of writers ― they were hurting.”

|

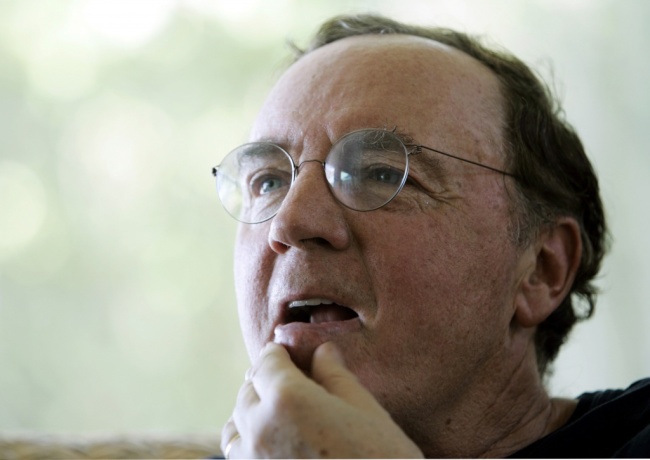

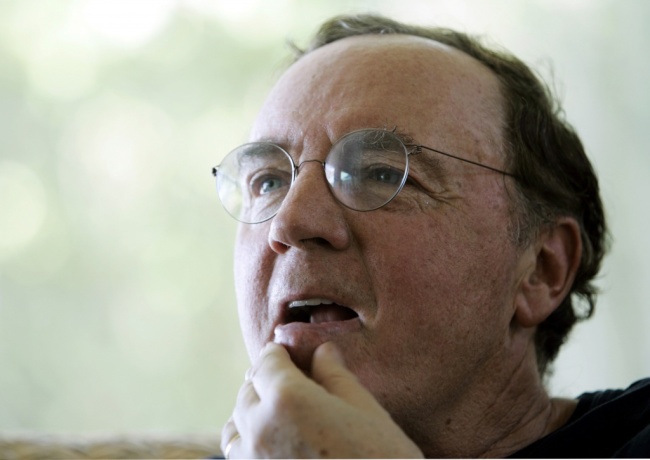

Author James Patterson (Wilfredo Lee/AP) |

Earlier this year, authors published by the Hachette Book Group saw their Amazon sales drop when the online retailer made it harder to buy their books as a tactic during contract negotiations. Because Amazon accounts for 40 percent of all retail book sales in the U.S., most authors feared alienating the company. Patterson (published by Little, Brown, which is part of Hachette), got up at the publishing industry’s annual convention, Book Expo, and sounded the Amazon alarm, opening up a public discussion of the online retailer’s aggressive business practices.

Whether through his sharp analysis of the publishing industry, the more than 400 teacher scholarships he funds, student reading programs he sponsors, or online campaigns designed to reach the president, Patterson emphasizes the idea that reading is necessary and that a vital literary ecosystem is as important as clean water. “What kind of culture would we have without books?” he asks, his voice rising.

It’s rare for a heavyweight author to engage with the world the way Patterson does. Some live guardedly behind walls. Others dedicate themselves to the project of writing. Patterson, who spent 25 years in advertising at J. Walter Thompson before leaving to write full-time, has found a different balance.

Maybe that’s because he is in a class of his own. Over time, he has sold more than 300 million books; in the last decade, that’s more than any other single writer. In 2009, you could take the combined book sales of John Grisham, Stephen King and Dan Brown and still not equal Patterson’s. He holds the Guinness world record for most entries on the New York Times bestseller list and regularly tops Forbes’ list of top-earning authors.

To be as prolific as he is, Patterson now works with coauthors on his novels. In addition to Alex Cross, he has other series for adults ― the Women’s Murder Club, NYPD Red ― and stand-alone novels, including romances.

After his son Jack was born, Patterson began writing books for kids too. The week we spoke, his new middle-grade comedy, “House of Robots,” was hitting bestseller lists.

“They’re actually in my wheelhouse,” Patterson says of writing comedically for kids. “I don’t like guns, I’m not really a violent person at all, but I think I’m pretty funny.” He regularly visits middle schools to talk with students and teachers. “The kids’ stuff is where I would have been, all things being equal, right from the beginning. I would have written funnier adult books, but there was nowhere to sell ’em.”

Patterson worked his way through college; he began thinking about books and writing while working long shifts at a mental hospital. Now 67, he sits down to write every day; he uses a pencil. “My desk right now is just covered with papers,” he says. “This year, I have done ― and I’m not finished ― over 1,000 pages of outlines. I love doing it; that’s one nice thing about it. But it’s a lot of work.”

Reagan Arthur, the publisher of Little, Brown and Co. and one of Patterson’s editors, says that when it comes to writing, he’s organized. What’s more, she adds, “He’s got a lot of ideas. I think he’s really interested in the world and in the way the world relates to books.”

Patterson’s campaign to #saveourbooks urges people to get Obama to be photographed reading a book. He wants to improve reading’s brand image, to make it of value to kids, because he sees it as essential to their success. “We could be saying, ‘Save Our Kids,’” he says. “I think there are two levels: One, bright kids should be reading more widely. ... The other piece of it are at-risk kids. If they don‘t become competent readers by the time they’re in middle school, how are they going to get through high school? How are they going to get jobs to make it out of high school? It’s so, so hard,” he pauses, and his voice changes to a more optimistic tone, that of a polished ad man.

“The thing about it is that we can turn around a lot of those situations,” he says. “As individuals, we can’t do a lot of things, we can’t fix up the national health program, but we can do things about getting kids reading.”

One of Patterson’s coming books features an inner-city kid who has invented a superhero, and the contrast provides comic relief. “For a lot of these kids, the only way they can imagine the problems of their neighborhoods being solved is by something larger than life: a superhero,” he says.

In a way, that’s Patterson’s role in the book world. His larger-than-life power is to apply resources and energy to the country’s literary ecosystem in multiple new ways. But instead of seeing himself as a savior, he reminds himself that success can be only incremental.

Patterson cites conversations with former President Bill Clinton about making a legislative compromise ― “it did more good than harm” ― and George Lucas ― “keep moving the ball up the hill” ― to frame his method.

“That’s a great practical philosophy,” Patterson says. “It did more good than harm. Move it forward, move it forward.”

For Christmas, Patterson will be hosting a small family celebration. His son will be returning to Florida from his New England boarding school, which Patterson says Jack loves. “You sit around these tables with a really good teacher and 10 or 11 kids who want to be there. It’s very stimulating; it’s hard to beat.”

Patterson has taught a few classes at his son’s school. “It’s great,” he says. “You wish that all kids could get that kind of school experience.”

He’s made it his business to visit schools in the inner city. He’s spoken to gatherings of teachers and principals. And this year, he donated one of his books to every sixth-grader in the New York City school system. Patterson is dreaming of something bigger in the future ― like presenting school libraries with a huge infusion of cash. Until then, he’ll keep moving it forward.

By Carolyn Kellogg

(Los Angeles Times)

(Tribune Content Agency)