Looking bored and uninterested, scores of first-grade primary school pupils stare at a question on the blackboard, the answer to which they seem to know too well.

“Can anyone guess what the answer is?” the teacher asks the class pointing to the question: 15-5=?

One student replies, “That’s too easy, we have learned that already.”

It is a typical interaction with her 38 pupils that frustrates Roh Eun-jin, 40, at Soongin Elementary School in northern Seoul. But she does not blame students.

“For them, the school curriculum is boring. They might rather do assignments for their private lessons than listen to what they already know,” she said.

“They surely know 15 minus five equals 10. But they can not explain clearly what subtraction means because they learned it by rote,” she said.

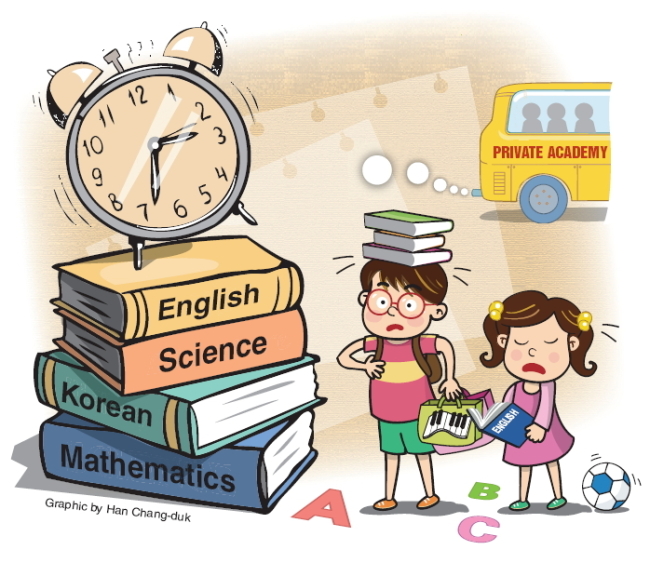

While compulsory education begins in Korea at age 7, most children start to learn at kindergartens and through private tutoring well before that.

Classes for first-graders usually run from 9 a.m. to 1:40 p.m. Most of them go to private institutes afterward, some taking more than three lessons a day, Roh said.

“Girls usually learn how to play the piano and other musical instruments and boys mostly take up physical classes such as taekwondo.”

After dinner, children also spend long hours working on various self-study courses or worksheets, she added.

“Students seem to learn too much even before coming to school, and that’s why some students lack interest and have a hard time concentrating in class,” said Nam Young-hee, another first-grade teacher at Soongin Elementary School.

Most of her pupils know how to read and write before staring primary education.

Although schools are not allowed teach English before the third grade, many of her class have already mastered basic grammar and vocabulary in the subject.

To alleviate the academic burden on young students, the government has started to reduce the number of subjects in elementary schools, and introduced new textbooks this year.

First-grade students now study only three subjects, down from the previous five: Korean, math and an integrated discipline.

The integrated study is a combination of academic subjects, such as history, geography and social studies, designed to develop students’ imagination, creativity and reasoning, according to the Ministry of Education.

“This month’s chapter is autumn, and students learn about the weather and traditional customs related to the season,” Nam explained.

Facing rising private education costs that have already contributed significantly to the nation’s heavy household debt, the government is also seeking new legislation to prevent primary and secondary schools from writing exam questions on areas not covered by the curriculum.

To deal with this, the Public School Normalization Bill was submitted to the National Assembly in May.

Roh said the new legislation, if implemented next year as scheduled, will bring big changes for students and schools.

“I think it will help ease students’ pressure to study and allow them gain more interest in learning.”

Roh, however, noted that she believed some students may still benefit from private lessons, given the current difficulties faced by public schools in teaching various skills and caring about students.

“The number of students per class at primary level is still high, and it’s impossible to meet the individual needs of each student,” she said.

Nam also noted that teachers simply do not have enough hours to spend on students due to other administrative work and miscellaneous tasks.

“We need more teachers so we can work more closely with those who need extra help learning,” Nam added.

To strengthen public education, the government is also planning to provide elementary students with after-school programs for free until 5 p.m. and free “evening care” services until 10 p.m.

President Park Geun-hye said the free after-school classes would replace private tutoring at hagwon and relieve the financial burden that private lessons place on parents, as well as keeping children of double-income parents safe until the parents finish work.

But the biggest hurdles are how to appropriate the mammoth budget required to fund the plan, and the lack of teachers qualified to lead such after-school classes, experts say.

Teachers admitted that even first-grade students have heavy study burdens ― 7-year-olds already spend an average 1,120 hours in class a year, excluding after-school classes.

“We currently run after-school classes until 5 p.m., all students can voluntarily enroll in the classes, and about 10 students from our class stay until the end,” said Roh.

That may well explain why Korean students outstrip other peers in reading and mathematics in a worldwide evaluation of student performances: Korea came top in science and math proficiency in a recent Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study test, which surveys the knowledge and skills of fourth- and eighth-graders around the world.

In the 2009 PISA assessments, Korea’s 15-year-olds ranked second in reading, fourth in mathematics and sixth in science among OECD countries.

Teachers say parents’ extraordinary zeal for their children’s education is definitely an important factor behind the performance of young Koreans.

But too much attention from parents can be problematic, and already many young students have to shoulder heavy academic burdens, according Nam Jin-hee, a 29-year-old elementary school teacher in Seoul.

In Korea, children’s education is now considered a competition between mothers, Nam added.

“Parents tend to compare their children with others. For instance, if their child got one wrong answer but others got full marks on a spelling test, mothers become stressed and push their child harder.”

Roh added: “Parents are so anxious about students’ grades, even at primary level, and if they think their child lags behind others they put their children in private lessons.”

There is a good sign though as some parents start to think differently and want to raise their child to be happy, rather than be stressed at school, according to Nam.

“However still our society doesn’t allow parents to do so, and pushes them to send their children to private lessons,” Nam added.

By Oh Kyu-wook (

596story@heraldcorp.com)