Comedy is having a moment. You can’t really talk about the vaunted New Golden Platinum Age of Television without reference to Louis C.K., Amy Schumer or Amy Poehler. Political discourse takes cues from Jon Stewart and John Oliver. The Internet, which drives the world, is three-quarters comedy (figure approximate). Tina Fey and Mindy Kaling write memoirs that also serve as manifestos, and the Children of Apatow sew their seeds through the culture, on multiple platforms.

We are also in a time when the nuts and bolts of show business have come to be regarded as entertainment in their own right. On television series like Jim Rash’s “The Writers’ Room” and David Steinberg’s “Inside Comedy”; Web series such as Jerry Seinfeld’s “Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee” and Paul F. Tompkins’ “Speakeasy”; on Scott Aukerman’s “Comedy Bang Bang” and Marc Maron’s “WTF” podcasts; and in the course of innumerable public panels, video chats and Reddit AMAs, the curtain is pulled back on the creative process.

|

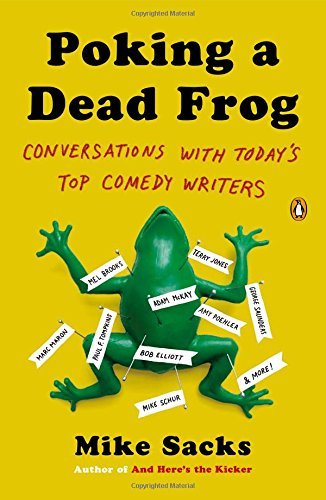

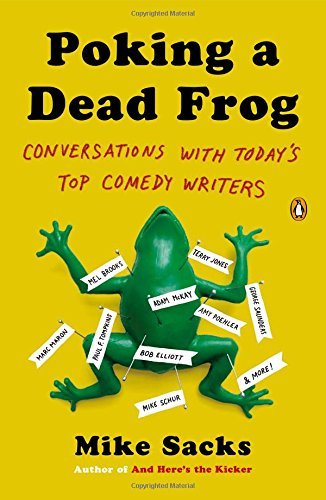

“Poking a Dead Frog: Conversations with Today’s Top Comedy Writers” by Mike Sacks. (Penguin) |

It comes in book form, as well. Mike Sacks, an editor at Vanity Fair and himself the author of the humor pieces collected in “Your Wildest Dreams, Within Reason” and coauthor of the parody guide “Sex: Our Bodies, Our Junk,” has a new volume of interviews, “Poking a Dead Frog: Conversations with Today’s Top Comedy Writers.” It offers a full hamper of humorists ― a few of whom are also performers, but most of whom are not ― discussing what they do and how they do it.

The pleasingly thick work, born to be well thumbed, is a sequel to Sacks’ 2009 “And Here’s the Kicker: Conversations with 21 Top Humor Writers on their Craft,” issued by Writers House, a how-to publisher whose other titles include “A Writer‘s Guide to Character Traits” and “The Weekend Book Proposal: How to Write a Winning Proposal in 48 Hours and Sell Your Book.”

Like its predecessor, “Dead Frog” offers learned advice for the aspiring comedy writer, with sections headed “Pure, Hardcore Advice” and “Ultraspecific Comedic Knowledge” alternating with longer interviews. (Some are just shorter, narrowly conceived interviews; a few seem to have been written by the subjects themselves; Sacks also includes the show “bible” Paul Feig wrote for “Freaks and Geeks”; Bill Hader’s list of “200 Essential Movies Every Comedy Writer Should See”; and the sample sketches Todd Levin submitted in 2008 for a job on Conan O’Brien’s “Late Night,” with his own current critique attached.

As seen here, accomplishment is the product of varying proportions of encouragement and discouragement, pleasure and pain, intention and accident. The interviews are not particularly jokey, but they are anecdotal often in a funny way.

The respondents represent a wide range of generations and mediums ― print, radio, film and, most frequently, television ― but this is overall a cavalcade of white men, a flaw in a survey otherwise wide-ranging. Among the women included are Poehler, Diablo Cody, cartoonist Roz Chast and former Onion editor in chief (now TV writer) Carol Kolb and, for me, the book’s great revelation, 96-year-old Peg Lynch, the creator, writer, star and copyright owner of “Ethel and Albert,” a presciently modern radio and then a TV show of which I had no previous knowledge. But humorists of color are conspicuously absent.

For the most part, the responses are descriptive rather than prescriptive: Like other sorts of writers, and artists, they can tell you what they did, and what they do, but not how you can or should do it. Every story being different, there is no universal set of instructions to make a career in comedy writing.

At the same time, common themes do emerge.

You should watch or read a lot of the sort of comedy you’re interested in writing, and then write a lot of it yourself, and then write a lot more. You should write what you think is funny and not what you think other people will think is funny. You can’t learn to be funny, but you can learn to be funnier. And as “Conan” writer Andres du Bouchet puts it, “If you can do anything else with your life and still be happy, do it, for crying out loud.”

The subjects include Mel Brooks, not just telling the usual stories; sitcom guru James L. Brooks, who believes that “Writing dignifies any turmoil it puts you through”; rarely interviewed “National Lampoon” cofounder Henry Beard; Monty Python’s Terry Jones; James Downey, who cocreated “Saturday Night Live‘s” Wild and Crazy Guys and the David Letterman “Top 10”; short-fiction writer George Saunders; graphic novelist Daniel Clowes; “Lemony Snicket” alter ego Daniel Handler; Bob Elliott, the Bob of Bob and Ray; Peter Mehlman, who coined “yada yada yada” and “double dip” for “Seinfeld”; Will Ferrell partner-in-crime Adam McKay; and “Parks and Recreation” writer Megan Amram, whose career began in Twitter, where she “started writing with the single goal to make myself a better writer and then, later, to get a job.”

Sacks is above all a fan, but he’s also a well-informed one. He asks productive, genuinely interested, insightful questions throughout, and, just as important, good follow-up questions: When “Parks and Recreation’s” Mike Schur talks about David Foster Wallace or James L. Brooks brings up Paddy Chayefsky, he doesn’t need clarification, but knows the territory, and lights out for it.

By Robert Lloyd

(Los Angeles Times)

(MCT Information Services)