ST. LOUIS (AP) ― The renowned Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York purchased a collection of 4,000-year-old Egyptian artifacts found a century ago by a British explorer, averting a plan to auction the antiquities that had drawn criticism from historians.

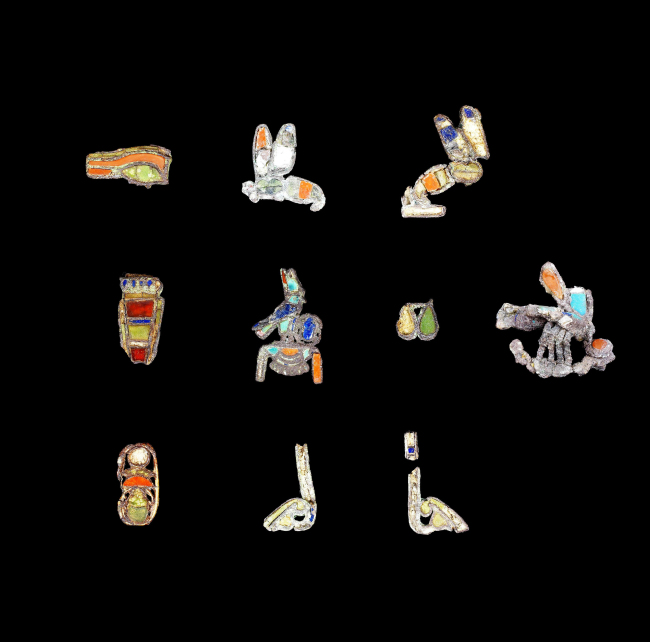

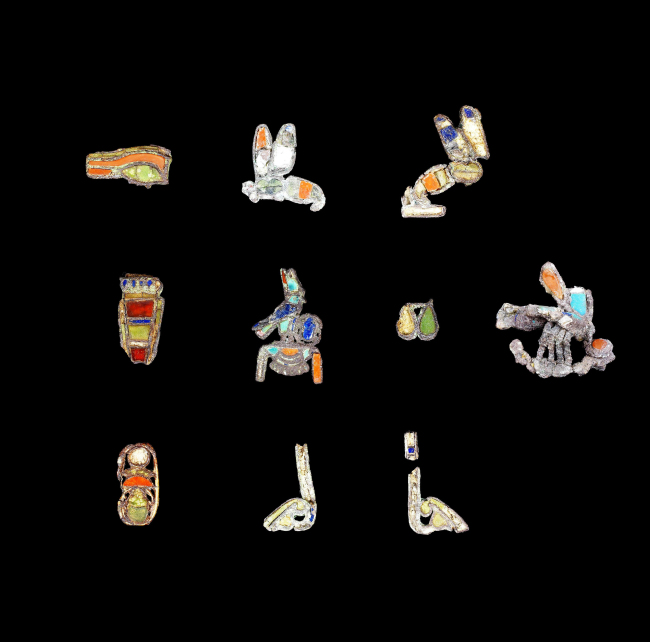

The Treasure of Harageh collection consists of 37 items such as flasks, vases and jewelry inlaid with lapis lazuli, a rare mineral. Discovered by famed British archaeologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, the relics date to roughly 1900 B.C., excavated from a tomb near the city of Fayum. Portions of the excavated antiquities were given in 1914 to donors in St. Louis who helped underwrite the dig.

The planned auction had been condemned by U.S. and British historians who feared the loss of a valuable cultural resource to the private marketplace. British auction house Bonhams withdrew the treasure Thursday, the planned day of sale, and announced the new deal Friday. Bonhams did not disclose the purchase price, but it had valued the items at $200,000.

|

Jewelry inlaid with lapis lazuli, a rare mineral, forms part of the Treasure of Harageh collection. (AP-Yonhap) |

The collection was owned by the St. Louis Society of the Archaeological Institute of America. It was initially housed at the St. Louis Art Museum and then at Washington University in St. Louis before it was placed in private storage two years ago.

The auction prompted the archaeological institute’s national office to rebuke the independent St. Louis chapter in a written statement that cited its “firmly expressed ethical position concerning the curation of ancient artifacts for the public good.”

Alice Stevenson, curator of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London, said a sale to a private buyer would have violated an agreement between the museum’s namesake explorer and the St. Louis group that the antiquities be distributed to public museums, accessible to both researchers and the public.

“Museums and archaeologists are stewards of the past,” she said. “They should not sell archaeological items in their collections for profit.”

Such auctions place other antiquities at risk by “providing incentives for global criminal activity that can lead directly to the loss of the art they claim to value,” she added.

Howard Wimmer, secretary of the nonprofit St. Louis group, said the society reluctantly decided to sell the collection when it became too expensive to pay an estimated $2,000 in annual storage costs. Society leaders were also concerned about properly preserving the artifacts.

“If there had been any way that we could have reasonably kept these items in St. Louis, we never would have pursued this course,” he said. “One way or the other, we had to find a new home.”

Doug Boin, a history professor at Saint Louis University, called the Met’s purchase “a happy ending for the collection.” But he expressed dismay at the St. Louis group’s approach, noting that another item from the Harageh excavation sold separately at auction for more than $44,000. Before the scheduled auction, the St. Louis society’s president, a Washington University professor, resigned in protest, and members remain dissatisfied, he said.

“We’re happy for the Treasure of Harageh to have been taken by a museum,” he said. “But we don’t feel like there’s been any resolution as to how we got here.”

Diana Craig Patch, the Met curator who intervened at the last minute to help broker the purchase, said the collection will complement the museum’s existing collection from the Harageh excavation.

“If it had gone to the private market, there is a very good chance (the items) would be resold separately, she said. “Context is everything to archaeologists. When pieces lose their context, they lost a lot of their history.”

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)