Professor emeritus of Kangwon National University Park Kyu-tek is a man of conviction. It is conviction that has enabled him to stick to a single, arduous path for more than four decades.

As a renowned taxonomist who specializes in moths, his path was far from glamorous and has only gained him recognition after decades of hard work in the lab and collecting specimens in the field.

Over his career, he has single-handedly identified more than 500 new species of moths from around the world. This feat, according to Park, puts him among the ranks of a handful of living taxonomists in terms of the number of new species identified.

He says the most important element to his achievement, which recently earned him the prestigious Sam-il Cultural Prize, was the perseverance to stick to his chosen path.

“The problem is that Koreans do not keep to one subject. When a new field makes advances, (scientists) flock to it to hold high-ranking positions, because that is how you get recognition (in Korea),” Park said.

He added that while taking such routes can bring fame and social status in Korea, those who choose that option are left without a specialty when they retire.

Because of this trend, which contrasts to foreign scientists, Korea is still far from producing a Nobel science laureate, he added.

“The reason for this is money. When you become prominent at an institution, you are given administrative posts, and when you are there, you have no time to do research.”

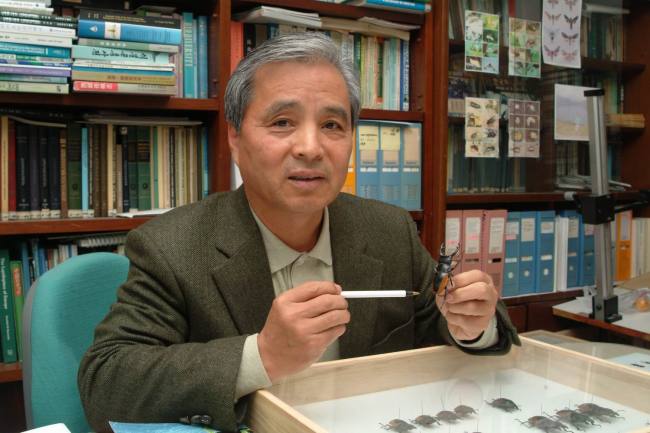

|

Park Kyu-tek at his office before retirement (Park Kyu-tek) |

Citing the time he spent as the deputy chief of the Korea Academy of Science and Technology, he said that people with administrative roles do not have the time to be academics.

“During the parliamentary audit, I went to the National Assembly, and all the famous experts were there to receive the audit because they were heading (government) institutions. (Korean scientists) do not decline such positions because focusing on research doesn’t bring social recognition.”

As a researcher with growing international fame, Park says that his career was not without temptation and that he even ran for the post of Kangwon National University president, but stopped himself in time.

“As I was campaigning, I stopped and thought, ‘is this my path?’ and concluded that sticking to my path was the best way for my work. Looking back now, I made the right decision.”

As he approached retirement, his perseverance paid off.

He was contacted by Florida State University in the U.S. with the offer of a post after retirement. Rather than wait for retirement, however, Park chose to resign and left for Florida.

“More than half of the papers I have written in my life were written when I was in Florida. I had no presence when I was in Korea, but because (of the time I spent abroad) I was able to receive global recognition.”

Even now, while retired, he continues to receive specimens from across the world with requests for him to identify new species of insects, and he still publishes research papers.

Although he has had a long and successful career in the field, his description of how his career began sounds almost like an accident.

He graduated with a degree in agriculture and joined the National Academy of Agricultural Science. While working there, he and his colleagues were given the chance to be trained abroad, and as entomology was the least popular option it fell to him almost naturally.

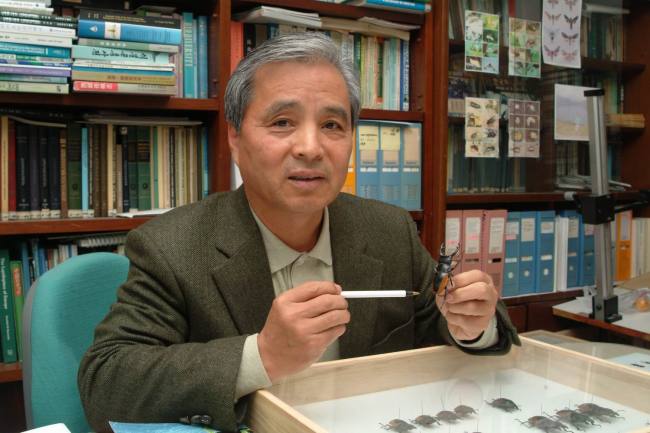

|

Park Kyu-tek collects specimens near the source of the Tumen River dividing China and North Korea. (Park Kyu-tek) |

After receiving training from a foreign specialist in Korea for four months, Park embarked on a year-long course in the U.K., where he says he found the main reason that set him on his current path.

“As I was looking through documents (in the U.K.) I found a report (on Korean taxonomy) written by the English in 1886,” he said.

“I had never seen anything like it, and thought the English came to Korea to do this 100 years ago, and that it was ridiculous that Korea still did not have the people (to conduct taxonomy research). I thought I would become that person.”

Since then, he stuck to his chosen path for more than half of his life, and now he wants to help new generations of Korean scientists to do the same.

In an effort to cultivate scientists with the preference to stick to one discipline, he says that he advises his students to think and to develop the ability to make good judgements.

“If you take the well-beaten path, all you have to do is run faster than others. But there are many paths to a target,” Park said.

“(I tell them) to find new paths. You may have to go around, but the way ahead will be unobstructed, so develop the ability to make that judgment.”

For more young people to choose the sciences, and to stay there, Park says fundamental changes ― ones that go much deeper than government policies or market principles ― are needed.

“Children need to be proud that their father is a scientist. They need to be able to boast that their fathers are research scientists. That is when people will choose the sciences,” Park said.

As for how to go about establishing such an environment, he said that the role of the media is important.

Citing one of the very few interviews he has conducted, he said that the news did more for the country’s sciences than nurturing hundreds of Ph.D. holders.

By Choi He-suk (

cheesuk@heraldcorp.com)