Only a month ago, the terror attack in Paris against satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo that claimed more than a dozen lives sent the world into shock.

What was rather shocking for university professor Lee Dong-yeon, however, was the level of political satire allowed in French society.

“France has respected political satire, viewing it as a right for free speech,” said Lee, who teaches Korean traditional art at Korea National University of Arts. “In Korea, however, there are certain subjects that cannot be lampooned publicly.”

Though democratic for nearly three decades, South Korea’s freedom of speech has been largely restricted, experts say.

|

Rat graffiti on a G20 poster painted by Park Jeong-soo, a university lecturer |

They say that powerful presidents, a history of military dictatorship and other structural problems have long hindered political satire from flourishing in Korean society.

The freedom of expression has suffered more under the back-to-back conservative administrations, the global rankings indicate.

International media watchdog Freedom House downgraded Korea’s press freedom to “partly free” from “free” in 2011, during President Lee Myung-bak’s term. It continues to be rated “partly free.”

Press freedom rankings by Reporters Without Borders also point to a dramatic fall in Korea’s free speech.

Its ranking peaked at No. 31 in 2006 during the liberal Roh Moo-hyun administration, but it dropped to No. 69 in 2009 during the first year of Lee’s presidency.

This year, Korea ranks 60 among 180 countries in the index, down three notches from a year earlier.

Clampdown on political satire and powerful presidency

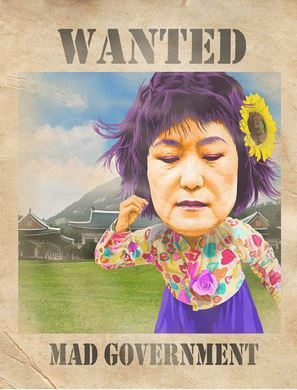

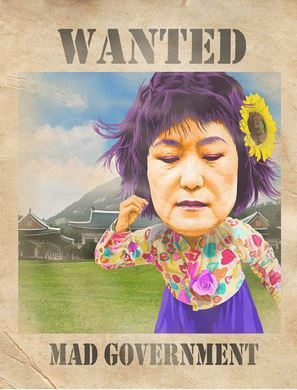

|

A flyer created by pop artist Lee Ha |

In recent years, a series of incidents showed how minor offenses, such as graffiti and scattering flyers, could be treated as serious crimes if done with satirical intent.

In November 2010, Park Jeong-soo, a university lecturer, was apprehended after spray-painting a rat on G20 Summit posters in Seoul, only a few days prior to the event.

Though Park claimed that he drew the rat, inspired by the initial in G20 that sounds like the Korean word for “rat,” the prosecution alleged that the graffiti was intended to insult President Lee Myung-bak.

President Lee was widely referred to as a rat by his liberal critics.

The court later ruled that the painting was “beyond what freedom of expression allows” and ordered Park to pay a fine of 2 million won ($1,800).

The high-profile case rekindled the debate on the government’s tolerance for freedom of expression.

“The Korean government uses heavy-handed tactics against criticism of the president, because people tend to refrain from voicing criticism after witnessing the heavy punishment faced by those against the government,” Park Ju-min, the lawyer who represented the lecturer, told The Korea Herald.

Park says such practices by the authorities have deterred Koreans from challenging political power, which poses a threat to the development of democracy in the long term.

This heavy-handedness has continued under the conservative Park Geun-hye administration.

In a similar case, a 21-year-old art student, surnamed Kim, was indicted in December after painting a caricature ridiculing the former dictator Park Chung-hee, the late father of the president. The dictator ruled the country for nearly two decades after seizing power in a military coup.

The prosecutors did not charge Kim with lampooning the former leader, but with damaging public property,

“(But if it were really about damaging public property,) why wasn’t I arrested when I painted graffiti to mourn victims of the Sewol ferry sinking?” Kim said in a media interview.

It doesn’t end there.

The painting “Sewol Owol” by local artist Hong Sung-dam, was pulled from the international art festival Gwangju Beinnale for its parody of President Park in August last year.

The painting, which depicts President Park as a puppet controlled by her father Park Chung-hee, had a political statement that was “too strong,” experts say.

Hong said that he wanted to lampoon President Park and those with power who he thinks should be held accountable for the Sewol ferry tragedy. More than 300 people, mostly students, died or went missing in the accident and many blame the government for its botched rescue efforts.

The cases point to the Korean government’s aversion to satire of the president, the traditional art professor Lee pointed out.

Behind the fear of political satire are what many see as an “imperial presidency” and Confucian culture that have prevailed for decades here.

“Korean presidents have been given an almost god-like status, which is a reminder of the country’s authoritarian past,” the lawyer Park said. “That’s why Koreans seem to fear the president.”

Concern looms over rule of law

|

The regular cast of MBC’s “Infinite Challenge” |

The limited understanding of satire in the political realm has led to abuses of the law by the government, experts point out.

One controversial invocation of the law came last October, when Lee Ha, a local pop artist, was captured by the police spreading flyers lampooning President Park from the rooftop of a building in Seoul.

Lee was apprehended on charges of trespassing though the owner of the building did not even report him to the police.

The 47-year-old pop artist said he was investigated for hours, with the police mainly asking about his political intentions.

“The question is ... would the police still apprehend him if the flyer did not bear a satirical image of President Park?” said law professor Hong Seong-soo from Sookmyung Women’s University.

In the flyers, the pop artist depicted President Park as an insane woman wearing a floral top and a blue skirt, with her eyes and ears closed. It read “Wanted” at the top and “Mad Government” at the bottom.

“Breaking into private property is clearly a violation of the law, but I think he would have only been cautioned by the police if his flyer had not targeted the president,” Hong told The Korea Herald.

“The government seems to use the law to suit its political agenda and silence dissent.”

But the authorities do not clamp down on every case of political satire about the president.

“Only high-profile people, who can wield influence, are selectively punished,” he said. “What I am concerned about is that such inconsistent enforcement of the law could undermine its reliability and stability.”

Professor Choi Jin-bong, who teaches mass communication at Sungkonghoe Univeristy, said the government’s actions showed a double standard.

“It seems like the government does not apply the same principle to its supporters,” Choi told The Korea Herald, in reference to right-wing activists who at times send anti-North Korea flyers to the communist country on the inter-Korean border.

It is a “double standard” by the government not to intervene in the flying of helium-filled balloons containing such leaflets, leftists have claimed. They have been opposed to distribution of anticommunist flyers, maintaining that it poses a threat to public safety by provoking North Korea to retaliate.

“It is not fair. Is this really how democracy works?” he asked.

Media self-censorship grows

|

Screenshot of “Dojjingaejjin,” a skit from KBS’ comedy show “GagConcert” |

In the mainstream media, a few Korean TV programs have tried political satire, but faced a backlash from what critics called “external forces.”

One of the examples is “LTE News,” a segment of SBS’ comic variety show “People Looking for Laughter.”

In one of the episodes that aired on Oct. 6 last year, the hosts satirized President Park’s controversial cabinet appointments and her absence in times of trouble.

“When any problem arises regarding her personnel, she happens to be on overseas trips. When her former spokesman Yoon Chang-jung was in trouble (due to his alleged sexual harassment), she was in the U.S. When prime minister-designate Moon Chang-keuk was at the center of controversy (due to his pro-Japan views), she was on an overseas trip in Asia,” said the two hosts in the episode.

A few days later, the episode was removed from SBS’ website, renewing questions about government censorship of the media.

Speculation swirled that the government exercised influence on the broadcaster to delete the episode, which was firmly denied by the program’s production team.

Professor Choi attributes the growing trend of media self-censorship to the system of appointing heads of public broadcasters.

“If the heads of public broadcasters are named by the president, the media cannot help but tone down its criticism as a measure of self-restraint,” Choi said.

Under the current broadcasting law, the heads of major public broadcasters ― KBS and MBC ― are selected by its board committee, dominated by pro-ruling party members. The president has to approve the appointments.

Some of the TV entertainment shows, however, have thrived on screen despite their satirical elements.

Among them are KBS’ “Gag Concert,” a long-running comedy show known for slapstick, as well as MBC’s “Infinite Challenge,” a variety program that uses role play and subtitles to offer satirical views.

“I like ‘Infinite Challenge’ because I can watch it thoughtlessly, but it touches on important social issues,” said Jung Goo-hoon, 27, who has been watching the show since it began airing 10 years ago.

The hugely popular TV shows run mildly critical segments on the government’s policies and social issues. But they still restrict themselves to safe targets, and strictly avoid the president and political elites.

“Viewers react sensitively to issues that can directly affect their lives such as tax policy or health insurance,” Choi said. “The government could not crack down on such satire that people can easily relate to because it could backfire.”

After all, those in power care about voter sentiment, he added.

To bring more political satire to media, producers and TV personalities should become more daring to experiment with their shows and challenge the established powers.

“Because that is the way to expand freedom of expression, albeit slowly,” Choi concluded.

By Ock Hyun-ju and Hong Hye-jin

(

laeticia.ock@heraldcorp.com) (honghyejin@heraldcorp.com)