|

Gizi Art Base in Seodaemun-gu, Seoul, functions as Park’s home studio and gallery. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

The following is part of a series that explores museums dedicated to Korea’s well-known contemporary artists that bear their name. --Ed.

A white porcelain moon jar, which resembles a full moon with its bluish hue, sits alone at the entrance hall at the Gizi Art Base in western Seoul, a place dedicated to contemporary art master Park Seo-bo.

“I do love the Korean moon jars. The jars are created through a repetitive movement on a pottery wheel, and the clay is the only ingredient. The whole process comes very naturally,” Park told The Korea Herald during an interview on June 16 at the Gizi Art Base.

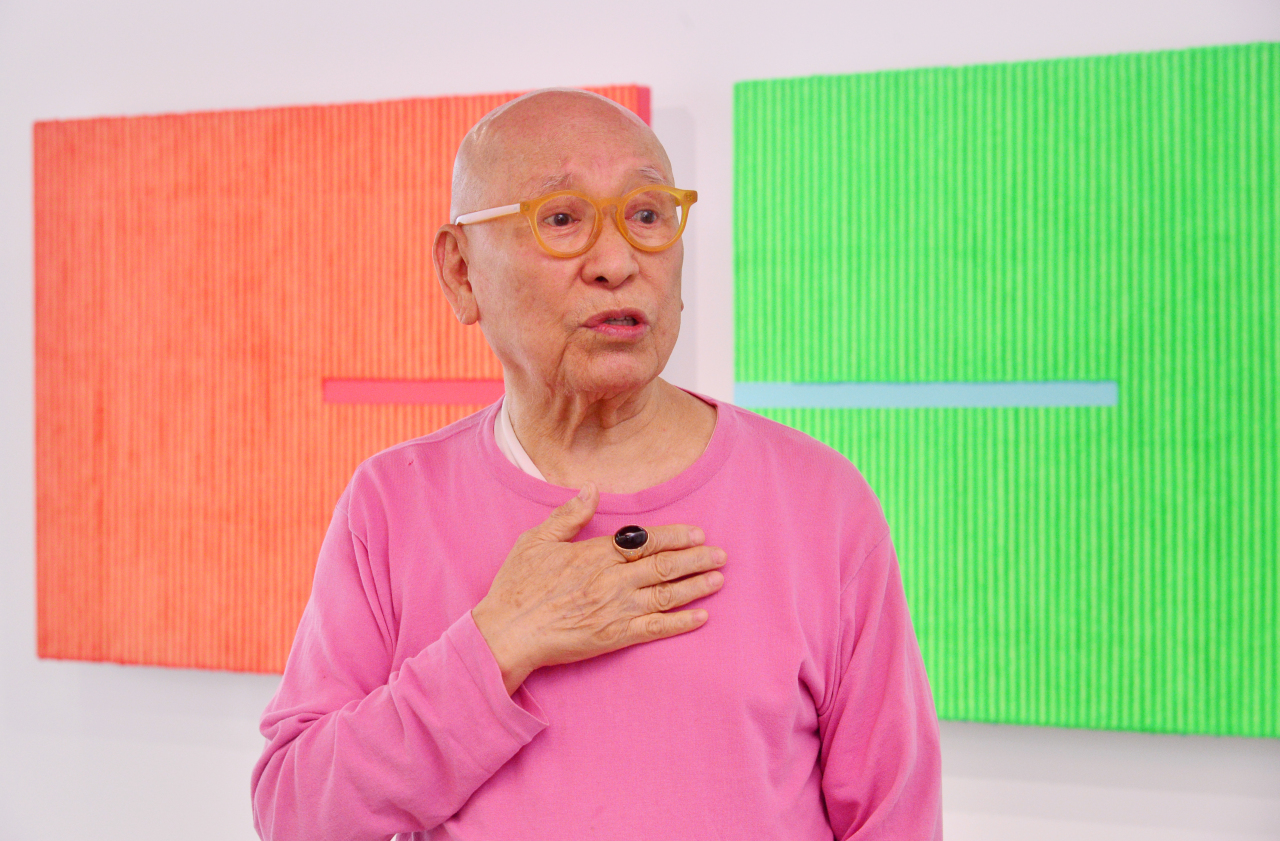

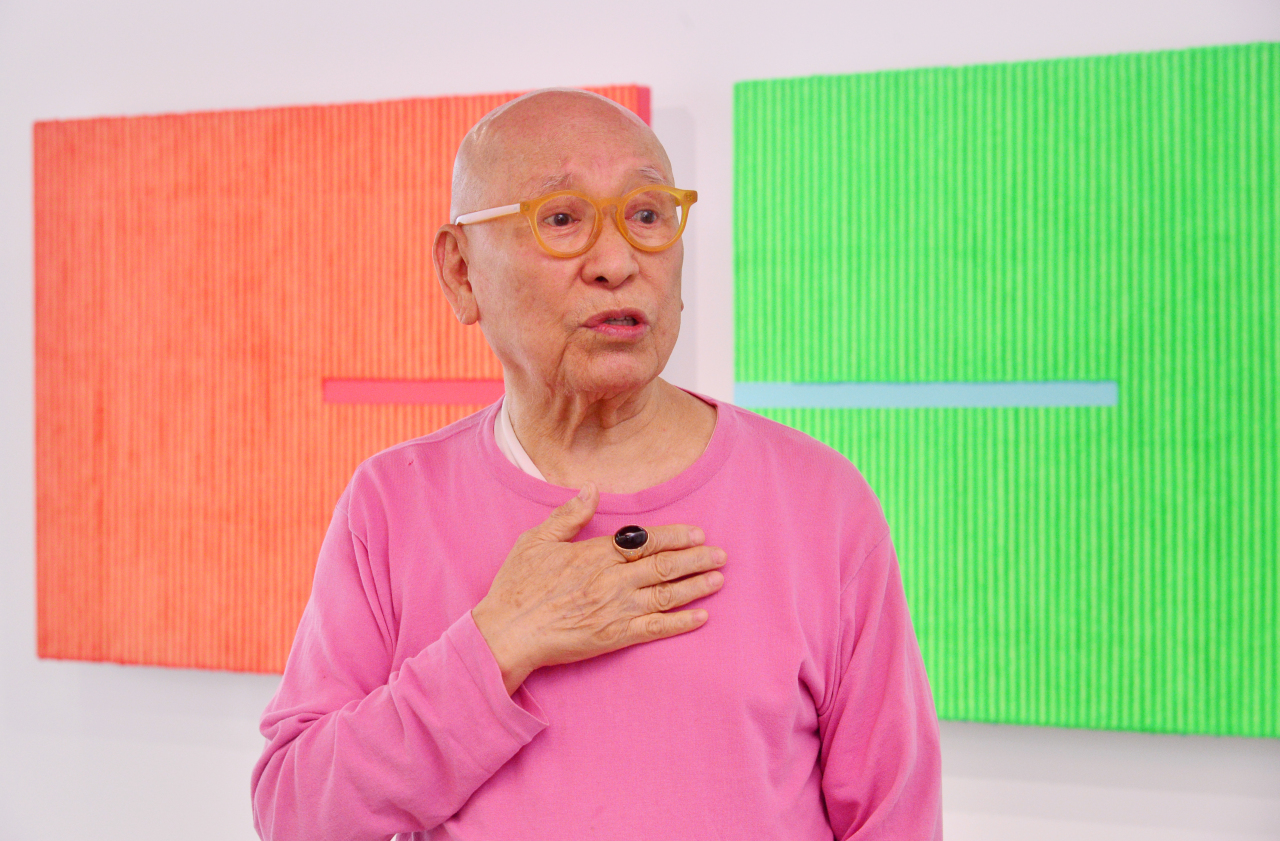

Park turned 90 this year. He moved to the newly built art base two years ago. The three-story building functions as a studio, gallery and a home for his family. On the first floor, some works of his color Ecriture series are displayed.

|

Park Seo-bo speaks in front of his color Ecriture series at Gizi Art Base in Seodaemun-gu, Seoul. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

“I do not paint this style (color Ecriture) anymore, since 2018,” Park said slowly walking through the hallway of the paintings, relying on a cane. Recently, Park has moved on to a new Ecriture series, which combine pastel colors and his early pencil Ecriture style.

His left hand slightly trembles when he gets tired.

“But my right hand is fine so painting is not a problem. I think God has helped me,” Park said.

Park, who still paints six to eight hours a day if his condition allows, is often called as the “untiring endeavorer” for his dedication to art. He hopes he could paint until he turns 100, if possible.

“I used to paint on the floor. But now I cannot do that anymore, because I would slump over. I use an easel instead,” he said. “I am not sure how many paintings (his new Ecriture series) I will be able to work on. It takes a few months to finish a single piece. I will not be selling them to anyone.”

Park began the Ecriture series 53 years ago, establishing his own philosophy of painting. The series was about self-discipline. To Park, painting is a form of meditation and an act of emptying oneself.

|

Some of Park’s color Ecriture series are displayed at the gallery in the Gizi Art Base. (Park Hyun-koo/The Korea Herald) |

He ceaselessly worked on the Ecriture series which started with pencil works that involved repeatedly drawing lines with a pencil on a canvas covered with white oil paint. Afterward, the zigzag Ecriture in the 1980s and the color Ecriture in the 2000s followed with variations.

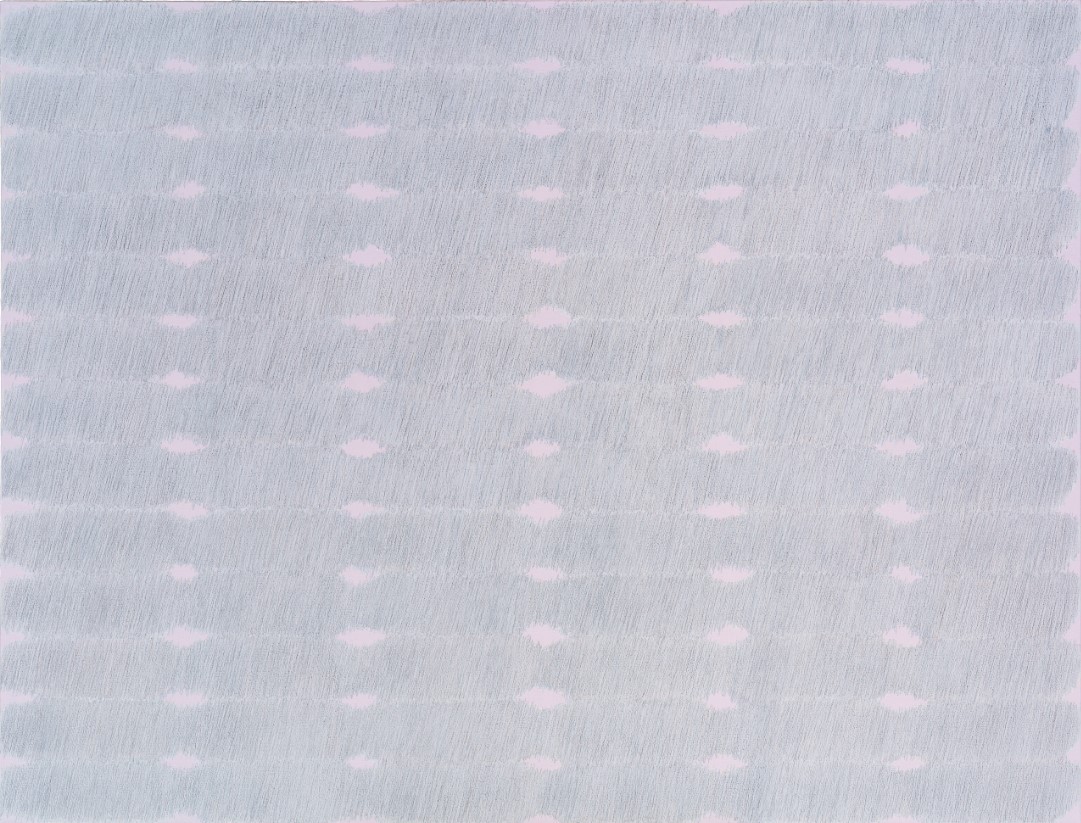

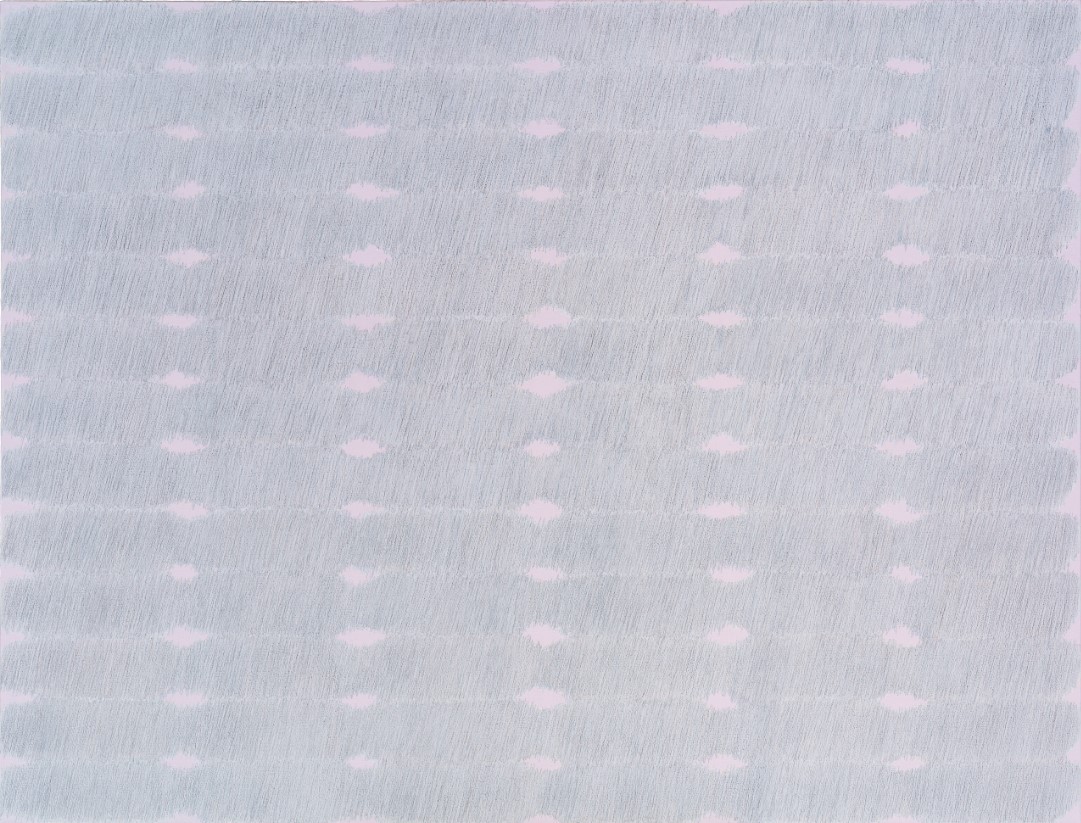

Park, however, revealed he finally began to enjoy painting at the age of 90. His new Ecriture series remind one of those of his early pencil Ecriture, but he painted the background with pastel colors that he once had no interest in. If seen from a distance, some of the series are reminiscent of clouds peacefully floating in the sky.

“Now I do not feel like fighting against the world, nor the need to struggle for myself. … I am enjoying the last moments of my life in a fine pastel tone,” Park wrote on his Instagram account. “I am having the time of my life.”

Park is one of a few Korean artists represented by two major internationally acclaimed galleries, White Cube and Galerie Perrotin based in UK and France, respectively. A retrospective exhibition on Park was scheduled to be held in April at White Cube Bermondsey but was pushed back to March 23 next year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

|

“Ecriture No. 190227” by Park Seo-bo; one of the artist‘s recent Ecriture paintings (Courtsey of the artist) |

Founder of dansaekhwa

Park led the dansaekhwa movement, the name of which translates to pursuit of “monochrome painting.” The art genre was evolved by a loose group of artists in the late 1960s and the 1970s who pursued self-discipline through artworks.

When it comes to dansaekhwa paintings, Park stresses three notions are crucial: purposeless action, a repetition exercise in meditation, and meditation evolved into material properties.

Birth of dansaekhwa stems back to when Park resigned his post as a full-time instructor at Hongik University in 1966. At the prestigious art university, he tried to reform the curriculum but was stigmatized as a rebellious figure.

“After quitting the job, I was sort of lost. I mostly stayed at home,” Park said. “Then I constantly asked myself ‘who am I?’ I tried to overcome the Western painting styles, but it seemed to be impossible,” Park said.

In fact, Park was the first Korean artist who applied Art Informel -- abstract paintings derived from Europe out of skepticism in the mid-1900s -- to his work. Park’s Informel painting “Painting No. 1” in his late 20s, is considered the first Informel art in Korea.

While constantly questioning the identity of his art, the old memories of when he visited Sudeoksa, a temple in Yesan, South Chungcheong Province, came across his mind. At the temple, he met a Buddhist nun who changed his life.

“I just graduated from college and asked her for tips on becoming a good artist. She suggested reciting Buddhist scriptures, which I did not want to do because I was not a Buddhist,” Park said. “Then she suggested I repeat my name constantly all day long.”

Park laughed at her at first. Then he asked whether she had met the Buddha by doing such discipline. Her answer struck him. “She said ‘Yes, I have met the Buddha. The Buddha was actually myself,” Park recalled how thrilled he was with the answer.

Park chewed on the conversation with the Buddhist nun and realized he had to empty himself. Park, however, did not know where to start. There wasn’t any art protocol to empty oneself.

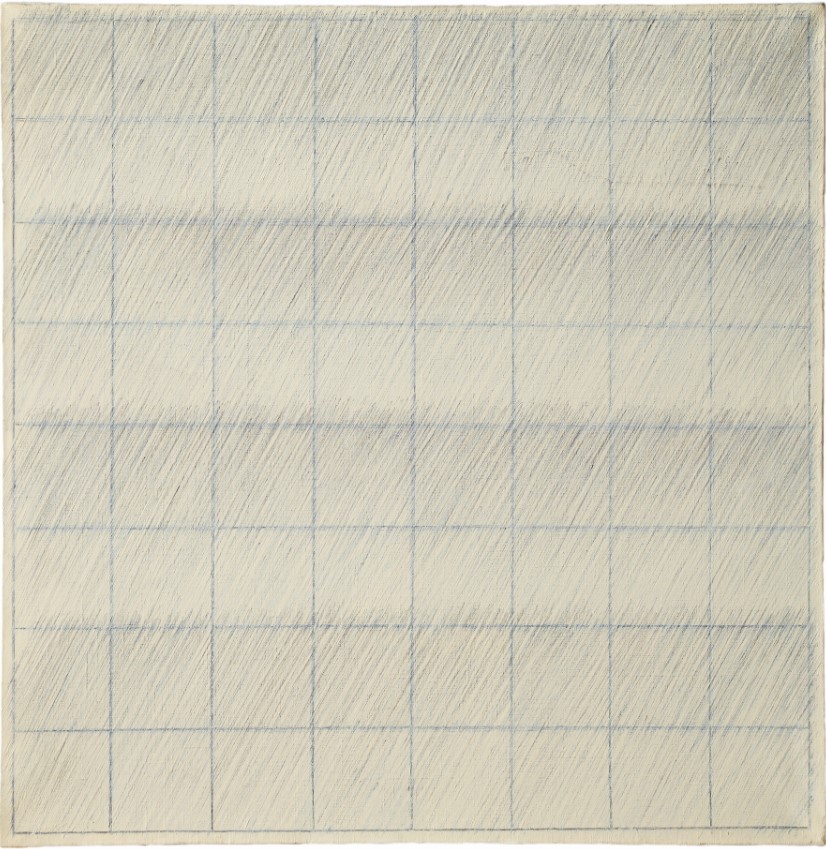

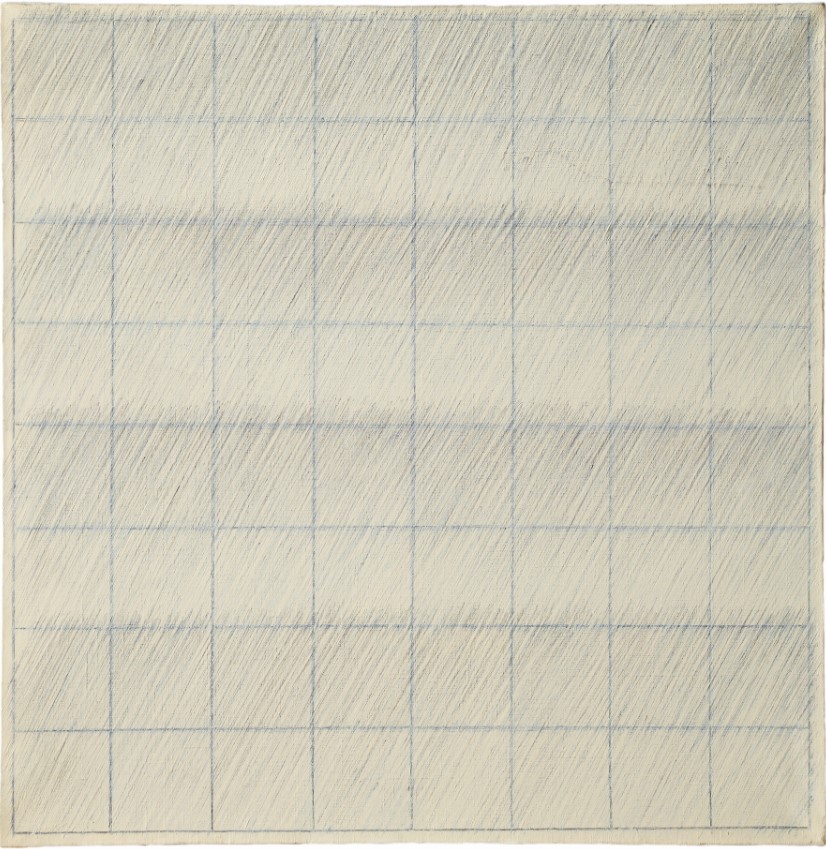

And it was his 3-year-old son who gave him a clue. One day, his son was practicing writing on squared paper. As he kept failing to fit each letter into the square, he started to scribble angrily with a pencil as if he was giving up.

“I realized such resignation was what I needed,” Park said. “So I drew a grid on a canvas and repeated drawing lines with a pencil out of resignation.”

|

“Ecriture No.6-67” by Park Seo-bo; one of his early pencil Ecriture series (Courtsey of the artist) |

He secretly practiced his pencil Ecriture series for five years, so that the new painting style becomes his own thing completely.

“You have to endure. If you try something new, it needs time to mature until it becomes a part of yourself,” Park said. “It is a pity that there are many artists who easily create art after catching a short glimpse of someone else’ works and unveil them to the public too quickly.

“I say ‘If you do not change, you will perish, but so will those who do,’ which means you have to change well. You will have to change over time, and it needs much endurance and maturity,” Park said.

He delved into the Ecriture series, sleeping four hours a day for five years, hiding it from others. One day, Lee Ufan, a close of friend of Park based in Japan, came across the paintings while Park left his studio’s door open.

“Lee was really surprised to see my new paintings. He suggested I put up an exhibition the following year in Japan, which turned out to be successful,” Park recalled. Park’s early pencil Ecriture works were shown to the public in 1973. Park came back to the university in 1970 hired as a professor.

Park’s Ecriture series is a strong representation of the Korean monochrome painting movement. Park, however, does not agree with the name. In fact, Park considers his paintings have nothing to do with monochrome paintings, which stemmed from an idea as opposed to polychrome paintings.

“Dansaekhwa is totally different from monochrome paintings or minimalism. Dansaekhwa is about emptying and purifying oneself,” Park said. “In Western paintings, painters mostly throw their ideas on a canvas. Dansakhwa is the opposite; it does not aim to reveal one’s ideas.”

The name of dansaekhwa stuck after the Gwangju Biennale in 2000 as the art critic Yon Jin-sup applied the term to artists of the painting style. The term spread fast globally.

“Now the term dansaekhwa is fixed, so I cannot do anything about it now,” Park said.

When asked for a better name than dansaekhwa, it took a few minutes for him to answer: “Well, perhaps the phrase of ‘working with nature’ may be the best expression.”

The title “Working with Nature: Traditional Thought in Contemporary Art in Korea” was the title of an exhibition of six contemporary dansaekhwa artists in 1992 at Tate Liverpool in the UK.

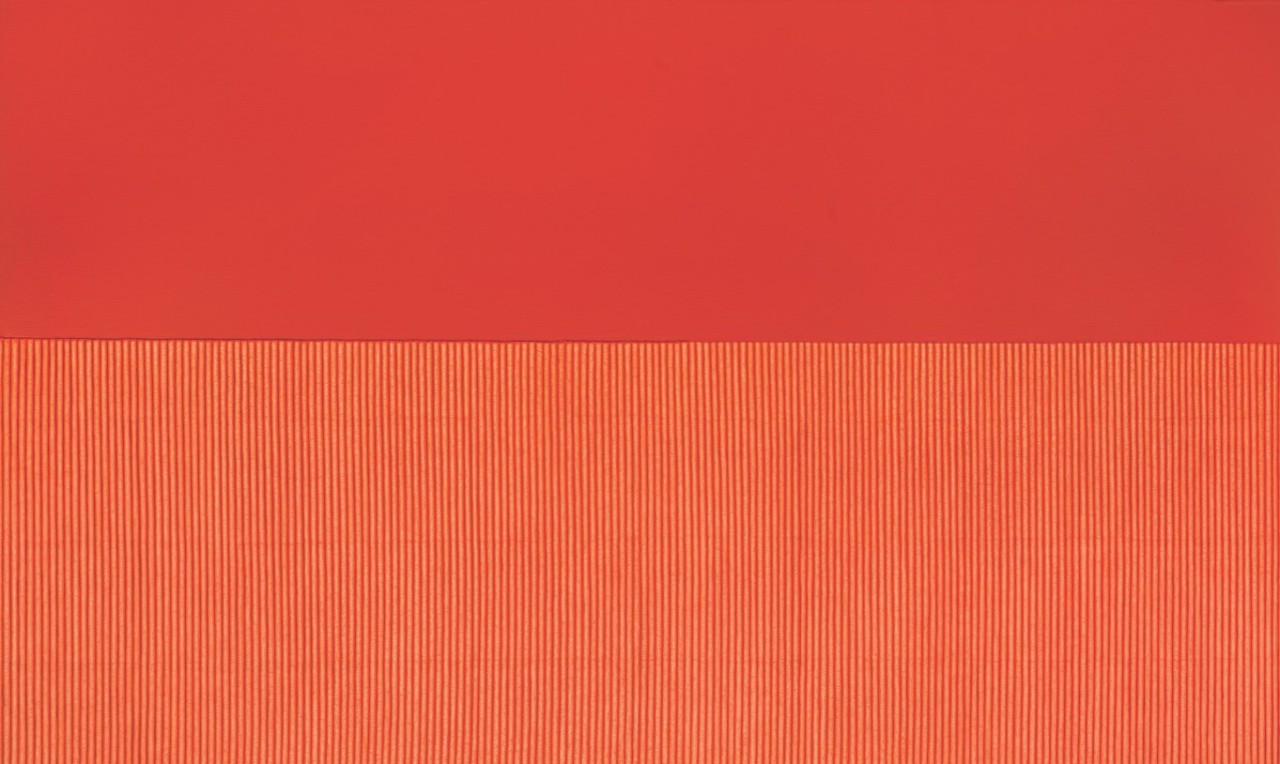

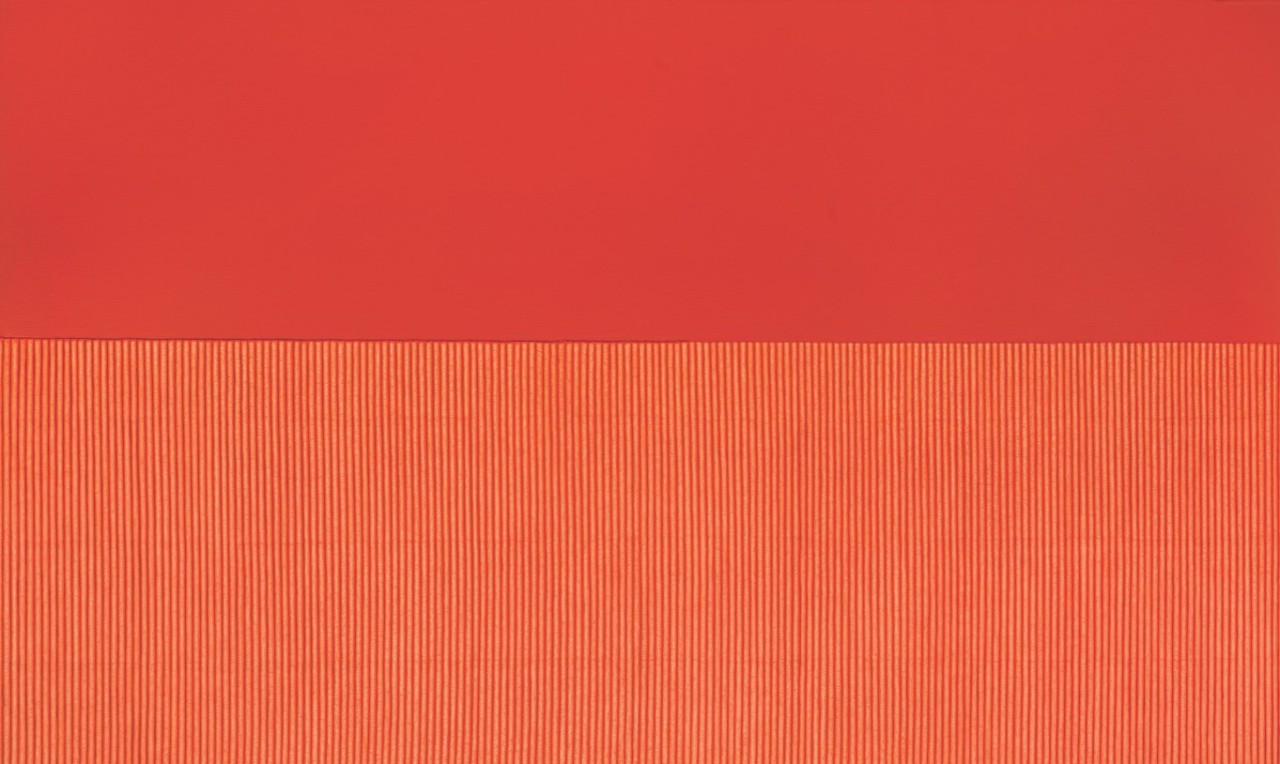

In the 2000s, Park began to apply colors, which he once did not enjoy, and used hanji, Korean traditional mulberry paper known for its high absorptivity, to his late Ecriture series.

“In 2000, I was astonished by the colors of maple trees in Japan. That was when I decided to apply colors of the nature to my Ecriture works aiming to heal people full of stress. I always learn from the nature.”

|

“Ecriture No. 071014” by Park Seo-bo; color Ecriture series were created from 2000 to 2018 (Courtsey of the artist) |

Finding originality from tradition

Park considers Korea’s unique identity comes from its view toward the nature.

The ancestors regarded the nature as a subject to obey rather than to conquer. And he said the perspective lives on until today, and it is artists’ capacity to embrace the philosophy for their art, representing the trend of the times at the same time.

“Look at the Korean moon jar. A potter could have made it fairly white, but it is not. Instead, there is a blue hue to make it ‘whitish.’ Koreans respected the nature and pursued neutrality,” he said.

Park said ways in which Koreans respected nature and were against humans’ control are found in many traditional activities.

“Think of the gayageum (a traditional string instrument). It echoes when you take your hands off the instrument. For seungmu (Korean religious dance), the white wide long-sleeved clothes continue to wave even if you stop moving,” Park said. “Everything has its own beginning when left free from human’s control.”

When asked what a good painting is, he said a good painting makes people feel comfortable, touches their heart and is original -- something that others cannot think of.

“I always strived to pursue art that others did not. It felt like walking on a ‘thorny path’ but still, I really did my best for my art. Looking back at the path, I now realize that I was happy,” Park said.

|

The Korean moon jar is displayed at the entrance hall in the Gizi Art Base. (Courtsey of the artist) |

Gizi Art Base

9-2 Yeonhui-ro 24-gil, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul.

For more inquiries, contact Gizi Art Base via its Instagram account: Instagram.com/gizi.foundation

By Park Yuna (

yunapark@heraldcorp.com)