|

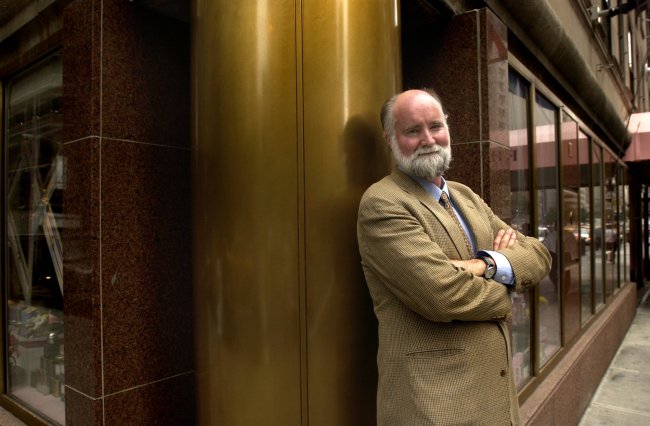

Author Nicholson Baker is photographed in New York City in 2004. (MCT) |

Nicholson Baker never meant to write a sequel to “The Anthologist.” And yet, he explains by phone from his home in Maine, the narrator of that 2010 novel, a poet named Paul Chowder, kept demanding to be heard.

“It was more a refusal,” Baker notes, “a refusal on Paul’s part to be overlooked. I was writing a different book, in my own voice, and I kept slipping into his voice. At a certain point, I just gave in.”

Baker’s new novel, “Traveling Sprinkler” (Blue Rider), picks up Paul’s story a few years after “The Anthologist.” He is 55, and at work on a new collection of poetry, which isn’t going anywhere.

As the book progresses, he gets involved in music, creating a suite of songs by which he hopes to reconnect with his ex-girlfriend Roz. He reflects at length on the French composer Claude Debussy, who died at 55.

If this sounds a little formless, a little loosely plotted, it is ― and gloriously so. “The novel,” Baker declares, “is the freest, sloppiest, most attractive form of writing. You invent a few obstacles for your characters, but mostly the idea is to re-create the textures of a recognizable life.”

For Baker, that’s been the appeal of fiction since his first novel, “The Mezzanine,” appeared in 1988. There, a young office worker buys shoelaces on his lunch hour: a narrative so spare as to almost not be a narrative at all.

“I’m a typical American person,” Baker says, “in that I only know about big things, big historical movements, secondhand. I have a fundamental dissatisfaction with using dramatic moments to propel the action forward. I don’t recognize those things. In ‘The Mezzanine,’ I had a biggish plot I’d scoped out, with some big Wall Street stuff, but in the end, I hadn’t seen any of that. What I’d seen was the moment in the middle of the day when you buy shoelaces.”

“Traveling Sprinkler” operates out of a similar premise, another portrait of the inner life. As in “The Anthologist,” Paul reflects on poetry and meter, and their relevance (or lack thereof).

Here, however, Baker takes Paul’s struggles further, highlighting his disenchantment with writing itself. “He’s wrestling with these poems,” he says of his protagonist. “He likes thinking about them more than actually writing them, which is why he starts making up songs.”

Like Paul, Baker began to experiment with music while working on the novel; the enhanced e-book will feature 12 songs, composed and performed by the author, including a charming little ditty called “Marry Me,” which keys a major moment in the book.

In that sense, then, “Traveling Sprinkler,” like “The Anthologist,” is an example of the novel as slice of life. The big subject, albeit largely understated, is how to make the most of the time we have.

“Where have I delivered something really good and beautiful?” Baker asks, a question that applies both to him and to Paul. “It’s just a book,” he elaborates, speaking for both himself and his character. “He’s just trying to write a book. Which is what I was trying to do.”

By David L. Ulin

(Los Angeles Times)