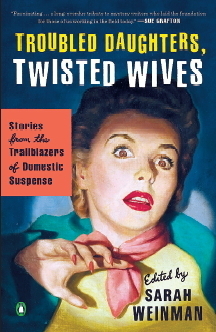

Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories From the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense

Edited by Sarah Weinman

(Penguin)

They are the forgotten women of mystery fiction ― female authors who blazed trails in the genre but whose work, for the most part, generally has been overlooked.

But thanks to the insightful collection of short stories and short bios in “Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives,” these authors are being remembered.

Sarah Weinman’s meticulous research and thoughtful approach illustrates why these 14 women writers highlighted in “Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives” are important to crime fiction.

These women’s writings “blur between categories, and give readers a glimpse of the darkest impulses that pervade every part of contemporary society,” writes Weinman in her introduction.

And it may be because of that blurring of genres that their work didn’t last. These authors wrote about “domestic suspense,” a term not familiar during the 1940s through 1970s when most of these women were writing. They “didn’t easily fit within the genre’s two marquee categories. ... the male-dominated hard-boiled story made famous by ... Raymond Chandler ... and the totally lighter and less violent cozy, which grew out of the success of Agatha Christie,” writes Weinman, a critic and Publishers Marketplace’s news editor.

Weinman also discusses how these writers set the foundation for today’s top female crime writers such as Gillian Flynn, Meg Abbott, Laura Lippman, Sophie Hannah and more.

A few authors in “Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives,” such as Patricia Highsmith and Shirley Jackson, will be familiar to most readers while others have maintained an avid, though smaller, following (e.g. Dorothy Hughes, who wrote the novel “In a Lonely Place,” and Vera Caspary, whose novel “Laura” became the 1944 Gene Tierney movie).

The stories in this collection are mostly about quiet desperation that erupts in the most unexpected ways, such as in Highsmith’s “The Heroine” and Jackson’s disturbing “Louisa, Please Come Home.” Each story, in its own way, examines a woman’s role in society (such as Helen Nielsen’s “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree,” published in 1959).

Part history lesson, part tribute, “Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives” is a must-have for crime fiction readers. (MCT)