WASHINGTON (AFP) ― In the half century since Martin Luther King’s march on Washington came to symbolize the Civil Rights struggle, black literature has found its place at the heart of American culture.

Before the era of King’s march, which was marked on Wednesday when huge crowds returned to the scene of his speech on the National Mall, books by African Americans were little known and rarely studied or celebrated.

But, as America learned to accept black citizens into its political mainstream and social life, so its literary canon was enriched by previously ignored or newly inspired authors.

These voices in turn contributed to a national conversation in which writers and thinkers were grappling with the history of slavery and segregation and with the realities of modern day racism and economic exclusion.

|

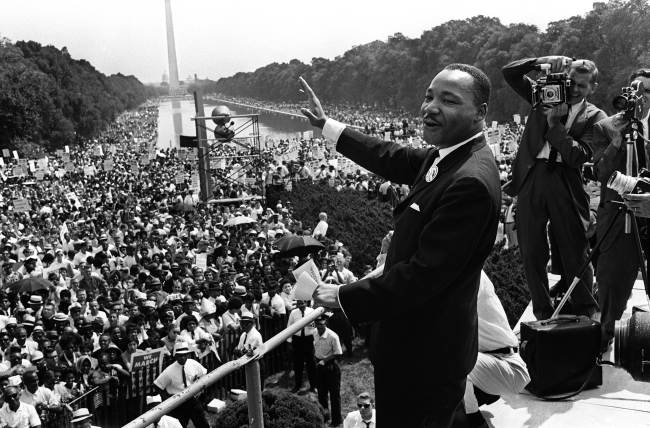

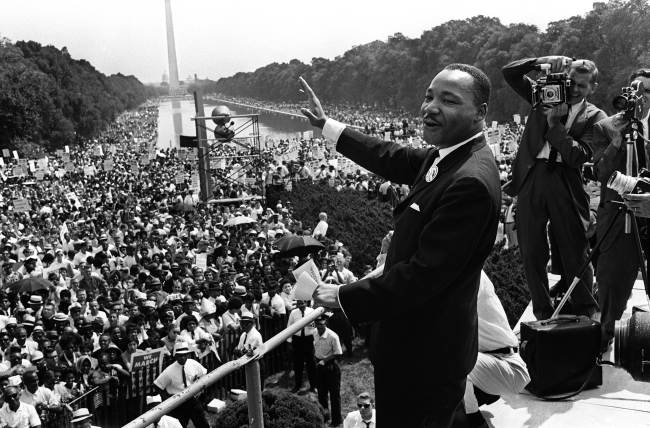

This Aug. 28, 1963, file photo shows U.S. civil rights leader Martin Luther King waving from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to supporters on the National Mall in Washington, during the March on Washington. (AFP-Yonhap News) |

“When I was studying at Stanford in 1962, we didn’t study black writers in American literature,” said Carolyn Karcher, a professor at Temple University, Philadelphia.

“There were no black students or teachers, or very few,” she added, recalling her days as an undergraduate in California.

“Today it would be impossible to follow this syllabus without studying African American writing. The Civil Rights movement inspired young blacks, who protested on campus for change.”

Since those days, some black Americans have won literature’s highest honors, including Toni Morrison, who won a Pulitzer Prize for “Beloved” in 1988 and the Nobel Prize for literature in 1993.

Writers such as Alice Walker, Pulitzer winning author of the 1982 novel “The Color Purple,” and Terry McMillan of “Waiting to Exhale,” have won huge sales as well as critical kudos.

And, in addition to enchanting casual readers, the works of African Americans have become subjects for academic study.

In 1968, inspired by poet Sonia Sanchez, San Francisco University opened the first school of Black Studies, a model soon copied on campuses around the country.

But the Civil Rights struggle did not simply open some space for black writing to be seen, it also inspired a generation of authors.

King himself, and the “I have a dream” refrain of his most famous speech, appears in several essays and books, particularly after his 1968 assassination turned him into a martyr as well as a hero of the struggle.

These works range from John Williams 1970 essay “The King God Didn’t Save” to Ho Che Anderson’s graphic novel “King.”

Walker addressed the Civil Rights struggle in her 1976 novel “Meridian,” its final chapter “Free at Last” named after a famous phrase from King’s 1963 address.

“King’s status as the central figure in a narrative of uplift and martyrdom has been cemented for two full generations,” said Greg Carr, of Howard University in Washington.

“He is rarely engaged critically, serving often as a salvific figure, mentioned in passing as a symbol of authenticity, purity or even, in protest fiction, derision.”