S. Korea’s lack of fishing regulations gives free rein to poachers

Spring has nearly arrived. Frozen rivers have regained their flow. I tie hundreds of flies, translate piles of Korean language maps and carefully pack the minivan for a weekend of fishing and camping.

Then a nagging question comes to mind: Where is my 2011 Republic of Korea fishing license?

The unfortunate truth is that South Korea doesn’t issue fishing licenses. Anyone can fish in Korea’s rivers and lakes. There are only a few restrictions at a handful of streams which are rarely enforced. Elsewhere in Korea, it’s legal to harvest and kill as many fish as desired.

Some restaurants serving “maeuntang,” a spicy soup made with any variety of freshwater fish, dispatch weekly crews armed with nets and iron crowbars to desolate mountain valleys, displacing large stones from riverbeds and capturing every swimming minnow, trout and snail clinging to life in the fragile alpine ecosystem. There are no rangers on patrol to stop this hideous rape of nature. These actions are unchecked and frequently occur in almost every mountain valley in the nation.

The Manchurian trout, National Monument No. 73, is found in areas from the Russian Far East, China, to North Korea, to the species’ southern limit in North Gyeongsang Province, South Korea. It grows an average of 8-9 cm per year, until reaching a maximum length of 70 cm. Unfortunately, most Manchurian trout fall prey to fishing nets or habitat loss before reaching sexual maturity in their seventh or eight year of life.

Korea’s national monument enjoys little legislative protection from the Korean Department of Fisheries. The only regulations available for view to the public are buried several pages deep at the National Legal Information Center’s website.

The few regulations that restrict angling are short moratoriums on a few specific species including the Manchurian trout. The regulations define fishing as prohibited inside national parks and state that capturing these species is prohibited during spawning periods. The rest of the year, it’s open season to slaughter without consequence.

As a result, numerous species of mammals, birds, and fish have gone extinct in Korea in the last 50 years, and several more are listed as threatened or endangered by the IUCE Species Program. A particularly interesting Korean language article about restocking an extinct char hit the headlines a few weeks ago. The story explains the disappearance and short-lived return of the white spotted char. The anadromous char has not been spotted since the early 1970s in Korea.

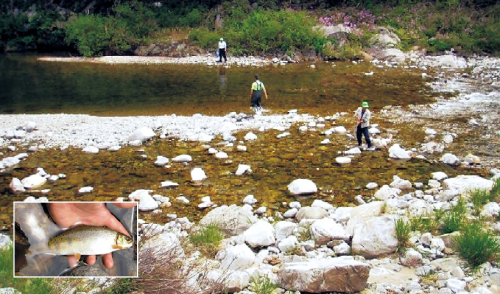

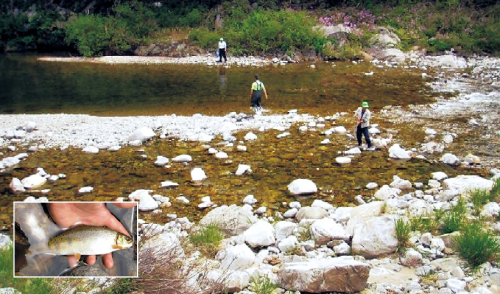

|

People use crowbars to lift rocks in search of minnow. (Insert) National Monument No. 73, the Manchurian Trout. (Matt Awalt/The Korea Herald) |

For decades, researchers surveying streams in northeastern Gangwon Province have been unable to detect the fish’s existence. Water misappropriation, stream degradation and poaching are factors blamed in the char’s disappearance from Korean streams. In an effort to restore the white-spotted char to streams along Korea’s northeastern coast, ichthyologists in Hwacheon County, Gangwon Province imported 100,000 eggs from a Japanese hatchery last December to a trout hatchery in Gumanri, Hwacheon County, for an artificial production program.

Usually reserved for rearing cherry trout, technicians at the Gumanri hatchery aimed to incubate the fertilized eggs before transferring juvenile char into feeding ponds. After spending several months in the feeding ponds at Gumanri, young char were scheduled not to be released back into their native creeks, but instead displayed as a feature attraction at the annual Hwacheon mountain trout festival that purportedly attracts over 1 million visitors, bringing a tremendous amount of tourist revenue to the sleepy town 30 minutes from the DMZ.

Unfortunately, the hopes of the festival planners were dashed. Until late March, conservation groups and anglers were optimistic about the hatchery’s chances of success. Last week, a spokesperson from Hwacheon City Hall announced “the hatchery had failed to produce a significant number of juvenile char necessary for moving the program forward.” Hwacheon County officials did not indicate if the hatchery would make a second attempt at artificial reproduction and emphasized that earlier attempts had been “solely for experimental purposes.” One might ask, what was the main purpose: To restore a species or to attract tourist dollars at a wildly popular fishing festival?

Recently, as I spent the day hiking in the area, admiring the luxuries of the natural world, I witnessed a disgusting and obscene act. Below in the creek, a group of people were electro-shocking a small pool with a 12 volt automotive battery. A few silvery minnows flopped to the surface. A man shouted as the others grabbed the meager harvest with long-handled nets.

Fishing licenses are desperately needed in Korea. The population of Korea greatly exceeds Canada. The landmass of Korea is the rough equivalent of Indiana. Korea’s fisheries are a limited resource that cannot support the current angling pressure. Regulating public access to Korea’s rivers and lakes could generate much needed revenue to low-income rural areas and create jobs within those communities.

However, Korea’s lack of a proper licensing system is only a drop in the bucket. James Card, an American journalist who spent over a decade in Korea, wrote, “The natural landscape of South Korea has been largely re-engineered, with nearly every river damned or forced into concrete channels.” Card’s criticism of Korea’s environmental stance is not unwarranted.

Several factors include: Construction sites, prone to severe erosion in the monsoon season; storm sewer discharge-surface pollutants flowing directly into rivers; and farmers re-routing creeks into irrigation ditches, leaving barren beds of exposed river rocks. The resulting low-water conditions raise stream temperatures and destroy the habitat for fish and several species of migratory birds that stopover along the Australasian Flyway.

Farms also discharge a significant amount of nitrogen-rich fertilizers into Korea’s river systems. The warm, slow-flowing, nitrogen-enriched rivers lead to massive algae blooms causing eutrophic dead zones. The nutrients cause “the takeover of nutrient-rich surface water by phytoplankton or other plants,” as explained by Tulane University’s Elizabeth Carlisle, who also wrote, “If nutrient pollution is not greatly reduced, fish and shellfish may someday be permanently replaced by anaerobic bacteria.”

South Korea celebrates Children’s Day on May 5. What will Koreans give to Korea’s future generations: progressive, environmentally-focused policies that outline a transparent framework of legislation to safeguard Korea’s wildlife and watersheds? Or will Korea’s waterways and native species continue to be viewed as prime targets for exploitation?

By Matthew Awalt (

mpawalt@gmail.com)

The author is an English teacher in Wonju, Gangwon Province, with a passion for fishing and the environment. He previously interned at Oregon State University’s Fisheries & Wildlife department. ― Ed.