Korean firms in electronics and shipbuilding industries are the first class in the world, while Korean financial service firms can only dream about becoming JPMorgans and Goldman Sachses someday. What does the future hold for Korean financial services industry? Conventional wisdom says either Hong Kong or Shanghai will become the regional financial capital in the Asia-Pacific century. As unlikely as it was for Samsung back in the 1980s to dominate Sony someday, one may envision an unlikely dark horse, Seoul, will emerge as the dominant financial center of Asia-Pacific in the next 30 years.

Is the vision only a day-dream or is it realistic? I believe it is entirely feasible because Korea is endowed with two extraordinary qualities. First, it has a superb geographical location in Asia-Pacific. Second, its people are exquisitely resourceful and adaptive. To become the financial capital of the Asia-Pacific region, however, Seoul first has to satisfy three prerequisites: national security, efficient institutions, and a large pool of quality financial professionals.

National security

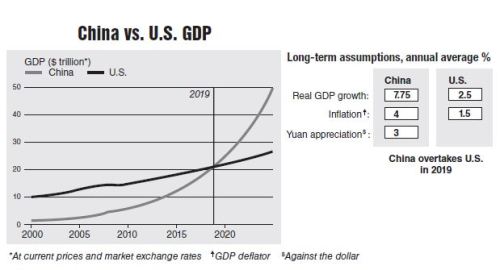

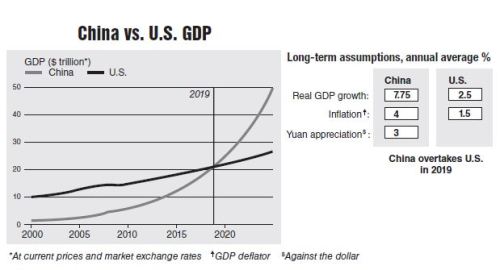

Today, Korea, along with Japan, Taiwan and Australia is doing more international trades with China than with the U.S. Yet, Korea cleaves to the U.S. for its national security. This dichotomy cannot last for long. China will surpass the U.S. in terms of GDP in as early as 2019, and no later than by 2024 (please see the graph above). The U.S. economy accounts for just over 23 percent of the world economic pie, yet its military spending, partly financed with borrowings from China, is over 50 percent of the global military spending. This mismatch between America’s economic strength and its military spending cannot last for long.

Korea will soon be eclipsed by China in a new world where the U.S. might be unable to protect Korea. This looming national security crisis, however, will present an extraordinary opportunity for Korea because China and the U.S. each will face their own crises. China cannot perpetuate the current one-party political system and it will inevitably have a political upheaval down the road. The U.S. economy cannot sustain current high level of military spending and its military supremacy will be forfeited as the defunct Soviet Union’s was.

Presently, China and the U.S. share common geopolitical objectives in the Korean peninsula. The two countries, whose armies fought against each other during the Korean War, will not yield the Korean peninsula to the other side, and they do need, and will continue to need, a buffer zone between their military forces in the peninsula. Capitalizing on their need to keep a buffer zone in the Korean peninsula against the backdrop of their looming internal crises, Koreans can reunify themselves by turning the whole peninsula into a buffer zone between the two countries. To do that, South Korea will first have to find a peaceful way to absorb North Korea into its capitalistic democracy, and it is clearly easier said than done. The two powers, however, may quite plausibly be amenable to keeping their military forces out of the Korean peninsula. Once the Korean peninsula is reunified as a buffer country, Seoul will soon emerge as the financial capital of Asia-Pacific.

The transformation of the Korean peninsula into a buffer country will have the greatest ramification for the future of Korea: Korea will forever break the 2,000 years old shackle of subservience to China and forever remove the threat of Japanese invasion. On the other hand, should Koreans be unable to reunify their peninsula by 2035, Korea will soon resume being a peripheral province of China as the U.S. by then only half as powerful economically as China will either be unable or unwilling to maintain the current military alliance with South Korea against China.

Institutional structure

At present, Singapore’s and Hong Kong’s institutional structures are far superior to Seoul’s; Korea will need to initiate institutional reforms. First of all, Korea will have to allow free international flow of capital into and out of Korea. Any politically motivated restrictions on capital flows such as the one that the Lone Star experienced with its investment in Korean Exchange Bank will have to be totally eliminated.

Korea will also have to offer lots of incentives to international capital so that it will choose to operate out of Korea. Specifically, Korea will need to offer lower taxes and efficient regulatory environments. The dense Korean jungle of rules and regulations where ineffective bureaucracy is the king must go. The insidious Korean culture of clan-loyalty must also be replaced with the culture of loyalty to good ideas. That is, Korea will not only have to institute a series of regulatory reforms, it will also have to adopt a fundamental change in its business culture.

The pool of quality professionals

International capital needs world-class professionals to put the capital at work. To operate well-functioning capital markets, Seoul will have to cultivate a large pool of highly-trained and bilingual financial professionals, both Korean and expats.

The universities in Korea will have to step up and educate a large number of bilingual, world-class financial professionals. In particular, the business schools must be fully staffed with professors who are bilingual and/or have real-world experiences. Korean students will need to become innovative and open-minded people, not just people who are good at rote memory.

The prediction

Which city in the Asia-Pacific region will emerge as the financial capital of the region in the Asia-Pacific century? Hong Kong and Shanghai are too vulnerable to domestic political currents and too China-centric in general to serve the entire Asia-Pacific region. Singapore’s human resource pool is too limited to cover the entire Asia-Pacific region. Tokyo carries too many historic baggage to service the Chinese or the Korean markets. That leaves only Seoul to emerge in the next 30 to 40 years as the financial capital of the Asia-Pacific region.

This forecast, however, is contingent upon three premises on what Koreans will do to capitalize on its superb geographic advantage: reach a national consensus needed to transform the Korean peninsula into a buffer country; adopt political and cultural reforms needed to institute and maintain the best financial systems under the sun; and Korean universities produce world-class, bilingual financial professionals. I believe Koreans will find the will and way to shape the future course of her history, and stop being a victim of it as she has been in the shadow of China and Japan for the last dozen centuries.

By Ken Choie

Ken Choie is a professor of finance at Sejong University. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan. Formerly, he was a portfolio manager at UBS in New York. He can be reached at kchoie@aol.com. ― Ed.