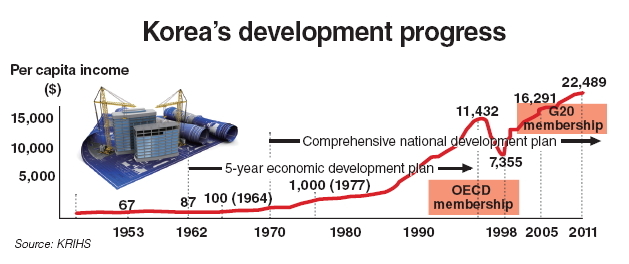

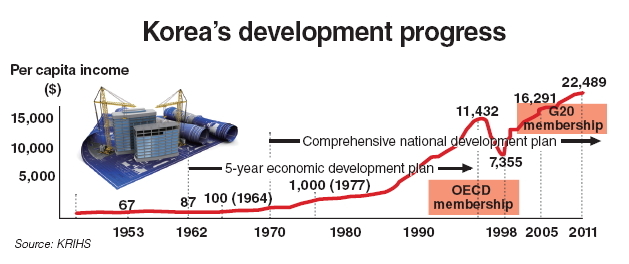

The Korean cities of Seoul, Busan and Ulsan enjoyed successful growth when the government aggressively implemented economic and land development policies in the 1960s and ’70s.

Government investment in these cities, backed by international aid, helped them to develop new industries and infrastructure and also fostered the essential human capital needed for economic growth.

Seoul has become a globally competitive city alongside Tokyo and Singapore, Busan is among the world’s top five port cities, and Ulsan has grown into the biggest industrial city in Korea.

|

Kim Yung-bong |

Now faced with a low birthrate, aging population and rapid globalization, the country’s major cities are at a critical point. Now is the time for Korea to renew its urban development strategy, said Kim Yung-bong, an independent economist.

This calls for an end to inefficient reallocations of resources from existing cities to new locations, and an upholding of market principles to help improve the self-sufficiency of Korean cities amid a population decline.

“We were able to accomplish the creation of something by (prioritizing) the development of underdeveloped areas because we had nothing then, during the Park Chung-hee era of the 1960s and 1970s,” said Kim, who is a professor at Sejong University’s college of social science and an honorary professor at Chung-Ang University’s department of economics.

“But it is time for market principles, not politics, to guide urban development in order to boost the self-sufficiency of our cities,” he said.

The private sector should be allowed to decide where companies are run, as business ecosystems are created in places where companies can boost human capital and profit, Kim remarked.

As well, the government should play a regulatory role over industrial zones chosen by private companies, and the regional and city governments should take consumers’ needs into account for urban planning, the economist suggested.

Should politics continue to influence urbanization, Korea is likely to experience further side effects like those seen in Gyeongju, North Gyeongsang Province, where local consumers complain about restrictions by the city government on big retail discount stores. The city has set these restrictions in place to gain votes from a large number of mom-and-pop store operators.

The creation of Sejong City, along with the so-called “innovation” and “enterprise” cities under construction nationwide, was politically motivated.

The new administrative city some 120 km south of Seoul was proposed by former President Roh Moo-hyun in 2002 to win votes from residents in the Chungcheong region.

The central government began dispersing its state-owned enterprises and agencies to “innovation cities” across the country as a means of politically alleviating discontent by regional and city governments when Sejong was chosen as Korea’s administrative city.

In another political maneuver, the government selected “regional enterprise cities,” hoping to attract companies in the areas of biotechnology, nanotechnology and tourism.

The 69-year-old economist said there is no other country in the world like Korea, where state-run institutions have been scattered and state ministries separated from the National Assembly and the presidential office.

“This is like couples living separately,” said Kim, who had long opposed government relocation plans. “They should be coordinating policies by staying close to one another.”

If the government really wanted to balance regional development by moving away from the densely populated Seoul metropolitan area, it should have chosen somewhere further south, such as near Gwangju in the Jeolla region, Kim suggested.

The Chungcheong region had been at the top in terms of regional growth, alongside Ulsan and Gyeonggi Province, before Sejong City was formed. Seoul, combined with Gyeonggi and Chungcheong, has been considered a single huge metropolis.

By Park Hyong-ki (

hkp@heraldcorp.com)