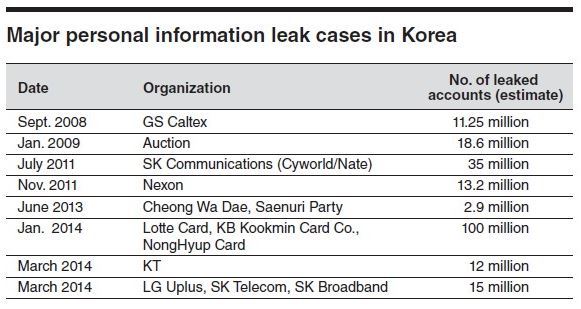

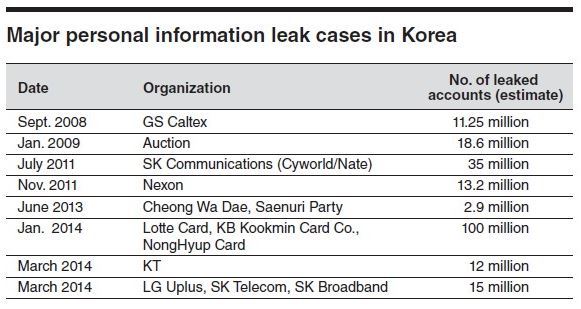

In July 2011, a hacking attack on SK Communications, operator of the once-popular social media site Cyworld, resulted in a data leakage involving over 35 million people. It marked the largest theft of personal data in the history of the world’s most wired country.

Three years on and some half a dozen cyberattacks later, cybersecurity experts say that virtually any Korean who sign on to a website, has a credit card or plays an online game should be aware of a scary fact: their personal data is actively traded on the black market in China and elsewhere.

The concern is warranted because similar large-scale data thefts continue to hit Korea. Back in January, over 104 million pieces of data, including a great deal of personal information of customers, were stolen from the major credit card firms KB Kookmin, NongHyup and Lotte.

Given the scale and frequency of personal data thefts, it seems that South Korea is not particularly skilled at protecting personal digital data.

The problem is that more and more people’s personal data is circulating on the Internet via social media and cloud services.

In a recent survey by the Korea Internet Security Agency, 95 percent of the respondents thought personal information leaks was the most serious problem brought forth by the use of the Internet.

The majority of the respondents also felt that companies which collect information have the obligation to protect such data, while over half of them said they would stop using the services hit by data leaks and seek other companies that provide similar services.

The data breaches were not confined to the wider public. In June 25 last year, a group of hackers attacked the homepage of the presidential office Cheong Wa Dae, regional offices of the ruling Saenuri Party and other organizations, stealing personal information of public officials and even members of U.S. Forces Korea. The South Korean government suspects that the hackers were North Korean.

“While it is important for Internet users to make the utmost efforts to protect their personal data, it is a primary duty of companies to supervise the information they have collected,” said Lee Kyung-ho, professor of the Center for Information Security Technologies at Korea University. He urged the government to take sterner measures toward companies which fail to protect their clients’ information.

In the aftermath of the hacking attack on credit card firms, the Financial Supervisory Service pushed for disciplinary actions against dozens of corporate executives. Punishing the companies, however, is only part of the solution, given that experts point out the broader vulnerabilities in cybersecurity faced by many Koreans.

“The fundamental solution to preventing data breaches lies in the encryption of personal information, a process neglected by many domestic websites,” said Jung Wan, a professor of law at Kyung Hee University and the head of the CyberCrime Research Forum.

While some people are opposed to the obligatory encryption of data, citing heavy costs and limited effects, Jung said the costs would turn out to be minuscule compared to the enormous damage caused by data breaches. “If personal information is encrypted, the hackers will find it hard to use the stolen data,” he said, adding this may stop hackers from viewing Korean Internet users as easy targets.

The chain of data leaks has propelled the government to take strong measures, such as the revised law that now prohibits nearly all companies and public institutions from collecting resident registration numbers.

The 13-digit numbers, which function like U.S. social security numbers, are assigned to each Korean at birth and are widely used for identification for everything from creating bank accounts to becoming a member of a website.

Both Korean and international hackers have targeted the crucial but often loosely handled resident data, leading to massive data leaks in the past few years.

In order to minimize the negative impact from the revised law, which will take effect on Aug. 7, the Ministry of Security and Public Administration introduced a system that allows Koreans to use their i-PIN online identification numbers for offline authentication as well.

Although the service is not perfectly safe from hacking, authorities said it would be a better alternative to the resident numbers since a user can just apply for a new PIN number if an account is hacked.

But i-PINs are issued based on the user’s resident number, which means mass data theft can still take place if an organization in charge of issuing i-PINs fails to safeguard the personal data.

Adding to the concerns of those who are already fearful about the security of their personal data, the culprit behind January’s massive data theft was a former employee of the Korea Credit Bureau ― one of the four government-approved organizations that can issue i-PINs.

By Yoon Min-sik (

minsikyoon@heraldcorp.com)