When Maria first came to Korea 17 years ago, the Filipina had no one to rely on, except for her Korean husband. Despite his support, it took more than a decade to finally be able to call South Korea her home.

From the language barrier and spicy food to the country’s patriarchal values, the 47-year-old, who did not want to use her real name, faced challenges every step of the way to adjust to life here, some 2,600 kilometers away from her family and friends in the Philippines.

|

(Ministry of Gender Equality and Family) |

“As I started to live with my husband’s family, I found it difficult to prepare food on traditional holidays and for Confucian ancestral rites. Unlike men in my home country, Korean men didn’t give a helping hand in cooking or washing dishes,” Maria said in an interview with The Korea Herald. “I could not even cope with Korean food, so I lived on eggs.”

“The most difficult thing is, of course, loneliness. I could not speak the language. I had no friends. There were not many Filipina wives back in 2000,” said Maria, who lives with her husband and two children in northern Seoul.

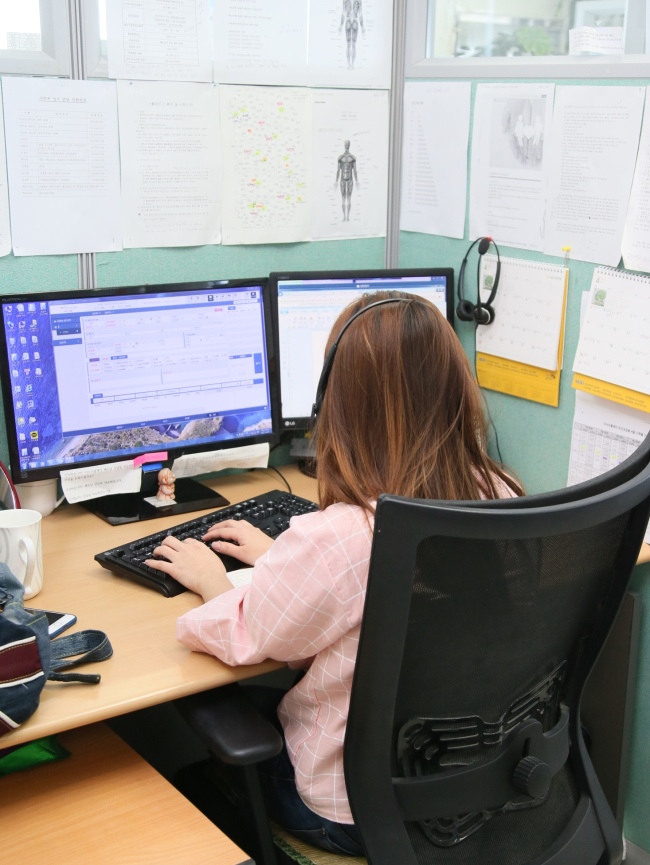

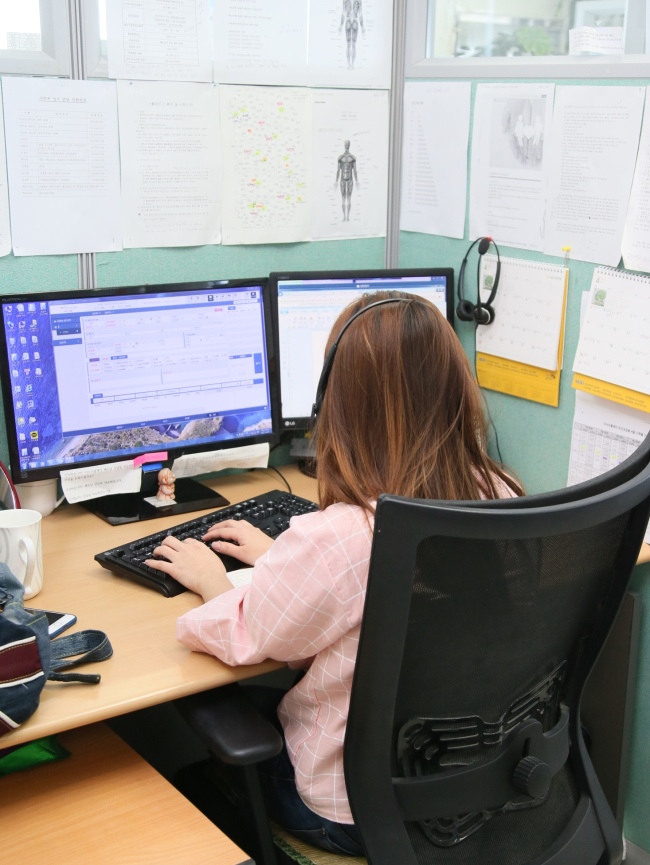

Her personal experience led her to apply for a job at Danuri Helpline -- a hotline mostly for foreign wives married to Korean men -- in 2006. She is one of the 99 counsellors at the hotline operated by the Korean Institute for Healthy Family.

The hotline provides translation and counselling services, and information on things ranging from Korean language programs and job opportunities to visas and government support. It also provides emergency aid and shelters for victims of domestic violence and sexual assault.

The counsellors at the state-run agency are foreign-born wives who have lived in South Korea for more than three years. They take calls from women from their countries of origin and offer services in 13 languages including Chinese, Vietnamese and English.

|

(Ministry of Gender Equality and Family) |

According to data from the Interior Ministry, the number of foreign-born spouses stood at 238,161 in 2015. The biggest group were ethnic Koreans with Chinese nationality, followed by Chinese, Vietnam, Filipinos, Japanese and Cambodians, the data showed.

Maria, who has offered services in Tagalog and English for 12 years now, said that she takes all kinds of calls.

Some ask for simple translations between Korean and their languages. Others seek information on what to do in response to the outbreak of a contagious disease, earthquake and North Korea’s launch of missiles into East Sea. There are also foreign wives seeking tips on where to find their favorite fruit from home, how to find lost belongings, how to apply for refugee status and how to begin a divorce process.

“Recently, I began to get more calls from Americans who had been sexually assaulted,” said Maria. “Until 2014, I got more calls from Filipinos coerced into selling sex at the US military bases. And those looking for their Korean husbands who abandoned them in the Philippines.”

|

(Ministry of Gender Equality and Family) |

In 2016 alone, Danuri Helpline gave counselling to 124,401 people through phone, face-to-face interviews or visits. The majority of their inquiries last year were about family conflicts (46.3 percent), followed by information on daily life in Korea (38.3 percent) and domestic and sexual abuse (10.3 percent).

A 32-year-old Cambodian woman, who only wanted to be identified by her surname Lee, was one of those who turned to Danuri Helpline for help in seeking a divorce. She only found out about her husband’s mental disability after arriving in Korea. The center matched her with a lawyer.

“I first got help from the center for interpretation to solve family conflicts in 2013. I could not communicate well with my husband and his family here,” said Lee, who got a divorce in February. “They hurled swear words at me. They forced me to work.”

Lee, who has to raise three children without a job or income, is now in the process of claiming childrearing expenses from her husband through a government agency.

“It is rewarding to help people like me to adjust to life here and not to go through the same hardships I experienced,” Maria said.

For migrant spouses, however, life still has challenges even after they get used to Korean culture and the long-distance relationship with their family back home, she said.

“Things have improved for migrants here, but there is still tendency of Koreans to look down on people from Southeast Asia. They appear to think we are poor and came here for money,” she said. “I just hope that I can contribute to making Korea more embracing and understanding of foreigners -- the country my children will live in.”

|

Counselors from Russia, China, Vietnam, Mongolia and the Philippines pose for a photo at the headquarters of Danuri Helpline, run by the Korean Institute for Healthy Family, in western Seoul. (Ministry of Gender Equality and Family) |

Migrant women who need help can call the Danuri Hotline at 1577-1366. It is available round-the-clock, 365 days a year. The services are available in 13 languages: Korean, Japanese, Chinese, Vietnamese, Tagalog, Russian, Thai, Mongolian, Lao, Uzbek, Nepali, Khmer and English.

They can also visit the Danuri Helpline’s offices for help. Its headquarters is in Seoul and branches in six cities -- Suwon, Daejeon, Gwangju, Busan, Gumi and Jeonju -- which are only open from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. during the week.

By Ock Hyun-ju (

laeticia.ock@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)