Since the end of the Cold War in the 1990s, the United States has struck various types of nuclear deals with countries seeking to develop their own nuclear weapons.

The most well-known examples are negotiations with Iran and Libya. The former is the latest country with which the US signed a nuclear-freeze deal -- though it is being criticized as a “failure” by President Trump -- while the latter is touted as a shining example for denuclearization by hard-liners in the Trump administration

With the cases of Iran and Libya emerging as competing models for denuclearization talks with North Korea, experts said neither can tell much about how the looming denuclearization process will unfold, as the reclusive country is in a completely different negotiating position from that of nuclear aspirant countries of the past.

“The denuclearization talks with North Korea will be unprecedented. I don’t think there are any historic references,” said Hong-min, director of the North Korean studies division of the Korea Institute for National Unification in Seoul.

|

North Korea`s leader Kim Jong-un met with President Moon Jae-in`s national security adviser Chung Eui-yong. Cheong Wa Dae. |

The US-North Korea denuclearization talks, if it happens, will be the first bilateral meeting aimed at dismantling operational nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missiles, whose capabilities were demonstrated in a series of underground nuclear tests and numerous missile launches over the past years.

After North Korea’s leader Kim Jong-un rose to power following the death of his father Kim Jong-il at the end of 2011, Pyongyang conducted the most powerful nuclear test last September and followed it up with the launch of an ICBM capable of reaching the contiguous US.

Pyongyang’s success in developing full nuclear capabilities sets it apart from other previous talks with nuclear aspirants such as Iran and Libya, whose nuclear capabilities fell short of Pyongyang’s and were nowhere close to developing a nuclear-tipped ICBM, experts said.

“There are few historical precedents of abandoning a nuclear-capable ICBM. … The negotiations with North Korea will be arduous and protracted,” said Ko Myung-hyun, a researcher at the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

After the Cold War ended, Ukraine and Kazakhstan ended up sitting on the nuclear arsenal and ICBMs inherited from the former Soviet Union. They gave up the weapons in return for the US economic aid and security guarantees.

Complicating negotiations are the inherent differences between Pyongyang and Washington on how to define “denuclearization” -- a point of contention that has hindered a major breakthrough during the decades-old nuclear standoff.

The Trump administration has maintained that Washington will not engage in serious negotiations with North Korea unless the communist regime takes what Washington views as “tangible measures” to achieve complete denuclearization.

During his call with Chinese leader Xi Jinping on March 9 after accepting Kim Jong-un’s summit invitation, Trump committed to maintaining pressure and sanctions “until North Korea takes tangible steps toward complete, verifiable, and irreversible denuclearization,” according to the White House.

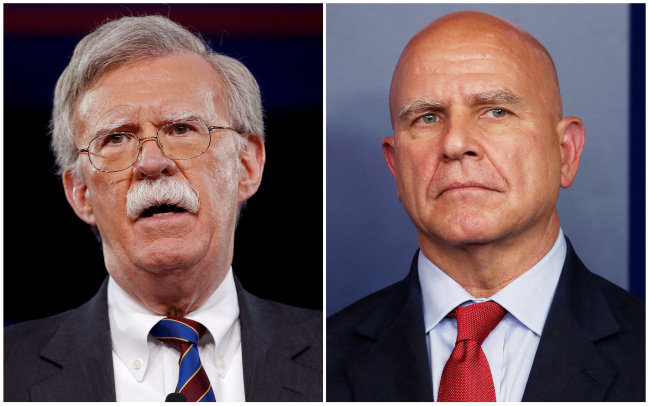

|

John Bolton(left), US President Donald Trump’s new national security adviser, and his predecessor H.R. McMaster. Yonhap |

That position has been bolstered since President Trump picked John Bolton as his new national security adviser this month. In his first interview since the nomination, Bolton said the talks should be a “straightforward” discussion -- similar to the denuclearization talks with Libya.

In late 2003, following nine months of secret talks with the US and Britain, then-Libya leader Muammar Gaddafi agreed to abandon his country’s entire nuclear arsenal. The components of the nuclear program were either destroyed or shipped to the US.

But there is no way that North Korea would follow suit, analysts said, as the demise of Gaddafi after making concessions to the US would be deeply rooted in Kim’s mind and would play into the negotiation process with the US.

“I think there is zero chance of a “Libya option” -- if by that we mean a comprehensive agreement to surrender weapons of mass destruction in exchange for promised engagement with the world community,” said Michael Mazarr, a senior political scientist at RAND Corp.

What North Korea will demand instead, Mazarr said, is “gradualism,” a slow step-by-step approach to drag out the denuclearization process -- just enough to forestall a US military action while buying time to earn benefits for the reclusive regime.

Such an approach is considered to be different from the Agreed Framework of 1994 and Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran, which both aspired to fairly comprehensive controls on a nuclear program while still allowing the country to retain some elements of a nuclear fuel cycle.

Given that Bolton and other hawkish US officials criticize the Agreed Framework and JCPOA as failed negotiations, the US is unlikely to accept the North’s offer and the bilateral differences over denuclearization will persist, Mazarr predicted.

“My fear is that the US administration will want much more than the North Koreans are willing to give in the short-term, and that, even to justify partial steps, North Korea will demand much more than the US is willing to concede.” Mazarr said.