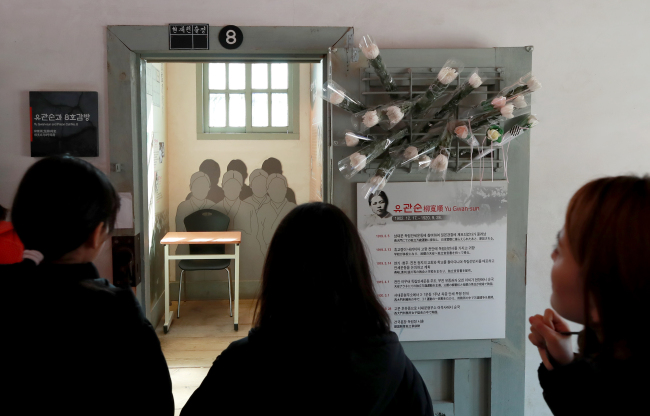

The Seodaemun Prison History Museum, a grotesque shrine dedicated to fallen patriots who fought Japan’s 1910-45 colonization of the Korean Peninsula, is holding an exhibition of artifacts related to their struggle and the March 1 Independence Movement of 1919.

The ongoing exhibition “100 Years of History Preserved in Cultural Heritage,” which runs until April 21, is divided into three sections. The first focuses on preparations for the March 1, 1919, protest and the simultaneous Proclamation of Korean Independence. The second deals with the birth of the provisional government of the Republic of Korea, which the Constitution recognizes as the direct forebear of the present-day Korean government. The third looks at what happened after Korea gained its independence in 1945.

|

Visitors take a look around the exhibition “100 Years of History Preserved in Cultural Heritage” at the Seodaemun Prison History Museum in Seoul in this Feb. 18 file photo. / Yonhap |

The Cultural Heritage Administration organized the event to commemorate the centennial of the March 1 Movement. The iconic nonviolent protest saw Koreans take to the streets shouting “Manse!” Similar to “hurray,” the word is used when celebrating good news or as a blessing -- in this case, for Korea’s independence.

Originally called Gyeongseong Prison (Keijo Prison in Japanese), the institution opened in October 1908 and is now best known for having imprisoned many of Korea’s early freedom fighters, including Kim Koo, one of the most important figures in the independence movement. The Japanese regime regarded these activists as traitors and kept a close watch on them.

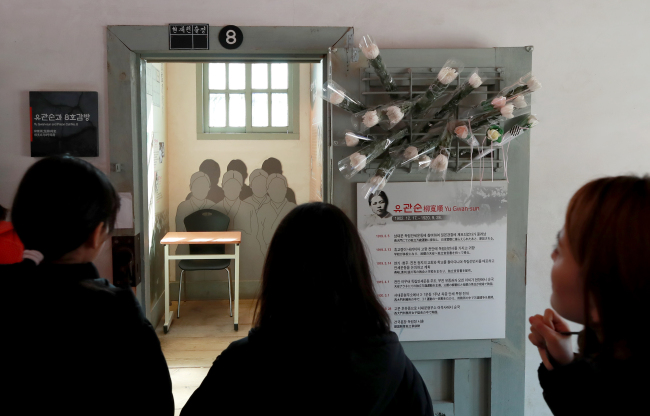

For the most part, the building retains its century-old look, complete with brick walls, watchtowers and cells such as the one where Yu Gwan-sun -- at age 16, one of the most celebrated leaders of the March 1 Movement -- was held before being tortured to death when she was just 17.

|

Visitors look at the cell that held Yu Gwan-sun at the Seodaemun Prison History Museum in Seoul, Tuesday. Yonhap |

The prison is notorious for its cruelty and for the tortures it inflicted: The upcoming film “A Resistance,” which depicts Yu’s final year, provides a glimpse of that infamous horror.

The museum serves as a haunting reminder of the brutality these heroes endured and the sacrifices they made.

An unyielding spirit

The first exhibit honors the late 19th-century scholar and poet Hwang Hyeon, whose work celebrated the patriots who resisted Japanese occupation. He took his own life in 1910 after Japan annexed Korea.

The poem he wrote on the day of his death is on display there, as well as a poem written by another independence fighter, Han Yong-un, as a tribute to Hwang. Records related to the assassination of Japanese statesman Ito Hirobumi by Ahn Jung-geun, and to Ahn’s subsequent trial and execution, are among Hwang’s writings.

In part one of the exhibition, one can also find prison identification cards for Yu Gwan-sun and 4,856 other Korean independence fighters who were held behind bars and tortured at the Seodaemun Prison. They include Ahn Chang-ho, Yun Bong-gil and Kim Maria.

Part one also features the only remaining handwritten works of poet Yi Yuksa, whose pen name comes from his inmate serial number -- 264, pronounced “yi-yuk-sa” in Korean.

Lee Bong-chang was a freedom fighter most famous for his failed attempt to assassinate the Japanese emperor. His declaration, which sets out what he intended to do so for his country’s freedom, is slated for recognition as a Korean cultural heritage item pending deliberation by the cultural heritage committee. It can be seen in part two of the exhibition.

One of the most important documents from the provisional government is the first draft of its ordinance, written by politician and educator Jo So-ang and registered as Cultural Heritage No. 570.

|

A group of visitors including Chung Jae-suk (first row, second from right), the chief of the Cultural Heritage Administration, take a look around the exhibition “100 Years of History Preserved in Cultural Heritage” at the Seodaemun Prison History Museum in Seoul in this Feb. 18 file photo. / Yonhap |

The final part of the exhibition features items that represent the fledgling state of Korea post-independence, including the Korean, Chinese and English lyrics to Korea’s national anthem, registered as Cultural Heritage No. 576.

Moments from the March 1 Movement will be relived at a commemorative event on Friday in the district of Seodaemun, central Seoul. At 9 a.m. in front of Dongnimmun (Independence Gate), a children’s choir will perform for 10 minutes and the head of the district office will read the declaration of independence.

It will be followed by a people’s march that will start at 9:20 a.m. and finish around 10:40 a.m. at Gwanghwamun Plaza.

Other exhibitions around Seoul commemorating the independence movement include “Centennial of Emperor Gojong’s Death and His State Funeral,” held from Friday until March 31 at the National Palace Museum of Korea.

The death of the monarch, the last king of Joseon and the founding ruler of the short-lived Korean Empire, is considered by some to have triggered the March 1 Independence Movement and the accompanying declaration of Korea’s independence.

The exhibition includes records, photos and other items related to the king, including his royal jade seal. Notable exhibits include a book specifying the protocols for Gojong’s burial and another on his final resting place, Hongneung, as well as a collection of his photos and an article on his death clipped from an Italian newspaper.

By Yoon Min-sik (

minsikyoon@heraldcorp.com)