Some hospitals in Korea have come forward in recent days saying they are being forced to move patients out of COVID-19 wards earlier than they should be in order to comply with government measures intended to boost bed turnover rates.

Despite the August mandate on larger hospitals to set aside some of their intensive care beds for COVID-19 patients, the current wave of the pandemic is straining Korea’s response capacities.

Korea has been seeing record-high numbers of critically ill patients amid a more-than two-month surge in infections. Although survival rates have improved, as younger patients now account for higher proportions, the overall number of critical care hospitalizations was now greater than ever at around 400.

Regarding complaints from some front-line medical workers, the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s spokesperson Son Young-rae said Wednesday the government was only providing guidelines “on discharges or transfers of patients at intensive care units” to help with decisions.

Son told a news briefing “the situation is being described as though the government is arbitrarily enforcing the guidelines while denying health care providers of their authority, but it is not.”

“Ultimately, medical professionals on the job are in charge of making the calls on whether a patient stays or not,” he said.

Dr. Lee Jacob, an infectious disease specialist at Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital in Seoul, rejected Son’s claims.

“Doctors’ pleas to have patients stay longer have gone unheeded most of the time,” he told The Korea Herald in a phone call following the ministry’s briefing. On the weekend his hospital had to move one patient out of a bed following discharge advice from the government.

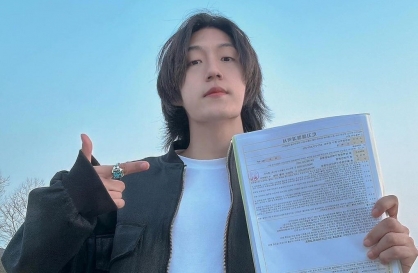

Lee said in a Facebook post Monday that the government COVID-19 response headquarters was “trying to get these decisions (about patient stays) done using paper.”

He uploaded a photo of an official document requesting discharges from critical care beds alongside the post.

The document said in the event the hospital does not comply with the government request to release patients in three days’ notice, it could face “administrative orders.”

“Doctors don’t get to have a say,” Lee said.

Dr. Eom Joong-sik, another infectious disease specialist at a government-designated COVID-19 hospital in Incheon, neighboring Seoul, said determining how long a patient should stay was “more complicated than that can be explained through records.”

The current standard for measuring “appropriateness of intensive care stay” is whether a patient needs breathing support called high-flow oxygen therapy.

“But sometimes patients develop severe conditions unrelated to oxygen therapy like kidney injuries requiring dialysis,” he said. “Even if their COVID-19 symptoms improve, patients can still suffer from other complications which can last long after the infection is no longer present.”

Little flexibility was allowed in keeping patients who are recovering a couple of extra days longer to ensure they are well enough, he added.

What was most concerning, he said, is that “the lack of regard for where the prematurely released patients may end up.”

“Vacant spots at ICUs fill up rapidly, and if patients that were let go early need to be readmitted, there may be no place left for them by that time.”

The guidelines for discharging COVID-19 patients from intensive care have existed for some time, but before the latest surge hit, there was little need to abide by the tight requirements. Beds were still available then.

On Son’s comments Wednesday Eom said he “do(es) not think the ministry would admit to it.”

He also pointed out the ministry spokesperson, who is not directly in touch with hospitals in the field, may not be aware of what was going on.

“The judgment of doctors working with patients should be respected,” he said.

Over the first seven days of September, Korea saw 45 deaths in total, while an average of 1,708 cases were logged each day. The deaths accumulated over the fourth wave, which took off early July, account for about 12 percent of all 2,330 deaths that occurred here since the pandemic began.

More than six months into the vaccination program, Korea vaccinated 61 percent of its 51 million people with at least one dose of a vaccine, nearing its goal to get to a first-dose rate of 70 percent by the Sept. 18 deadline. About 36 percent were fully vaccinated.

By Kim Arin (

arin@heraldcorp.com)