“The prices of foods in Korea should come down after the agreement. In Canada, my weekly grocery bill is about $22-25. Here my weekly grocery bill is around $80. Korean food prices are way too high. Looking at the wealth of the nation, these prices just don’t gel,” he said.

Das also believes an FTA could improve relations between the countries, especially in light of contentious incidents such as the recent killing of a Korean coast guard officer by Chinese fishermen.

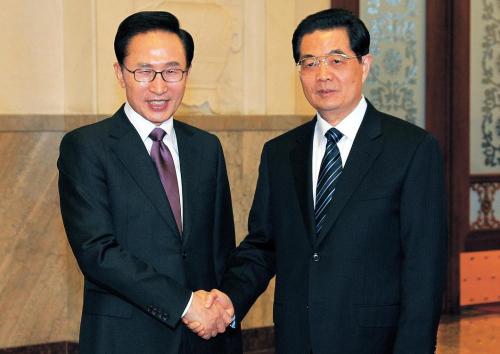

“As you noticed during President Lee’s state visit to China, while this issue was discussed it did not overshadow the negotiations of the two parties, and they know that the two neighbors, or I repeat the two dynamic economies, have a lot going for them and there are far more important issues than this one incident which sort of could mar the relationship.”

The region’s recent economic history, Das says, has convinced countries of the advantages of easier trade.

“The Asian crisis changed everything because all these countries together had to fight this crisis and it weighed heavily on many countries including Korea, not so much China. And so they thought, OK, if we have to come to help each other at a time of economic distress, well why not get into FTAs and BTAs. And economically, in the regional economy, that’s what they started doing.”

But even before a single round of FTA negotiations has taken place, opposition has been strong. The main opposition Democratic United Party recently called on the government to halt plans for talks with China, with Floor Leader Kim Jin-pyo claiming the deal would have a “nuclear” impact on Korean farmers and fishermen. KIEP estimates that an agreement that lowered tariffs on agricultural products by 50 percent would cause up to $2.8 billion worth of damage to the local industry.

“We have to look at this scenario in its totality,” said Das, “that whenever an FTA is negotiated, there are some sectors that lose and they are some sectors that gain. And here in Korea it is the farming sector that would lose.”

DUP lawmaker Park Joo-sun says not enough information has yet become available for him to take a stance on the FTA, but he is adamant that it should not follow the example of the U.S. pact.

“Firstly, amending the law and system of Korea through a single FTA treaty should not be repeated. Secondly, products produced in Gaeseong Industrial Complex should be recognized as products of South Korea. Thirdly, effects on agriculture, livestock and fishing industries should be minimized through policies such as specifying sensitive products,” Park said.

Park says that a pact with China has the potential to be even more damaging to local agriculture than the Korea-U.S. FTA his party opposed in its previous incarnation as the Democratic Party.

“Agriculture, livestock and fishing industries should be dealt with extreme caution. Unlike the U.S., China produces the same agricultural products as South Korea does. Also, its geographical proximity eliminates concerns regarding freshness of the products which is the most important aspect of trading agricultural products. Furthermore, regarding the price competitiveness, Chinese agricultural products are overwhelming priced at 1/3-1/4 of the price of Korean products,” Park said.

Nam Hee-sob, who was a chief member of the policy committee of the Korean Alliance against the Korea-U.S. FTA, shares many of Park’s concerns.

“In general, the FTA is to reduce the tariffs which may lead to a reduction of prices. But I think it is just one side of the thing. I think it is meaningless to get a cheaper product at the expense of our food system. We cannot entirely rely on the Chinese food,” Nam said.

KIEP’s Kim, too, acknowledges that farmers would need to be compensated for their losses.

“It is also very important for the Korean government to make appropriate policies to share fruits from free trade and to help the people who would be unfavorably affected by the FTAs,” he said.

But Nam says that rather than seeking cheaper imports to tackle high food prices, the focus should be on reform of the local industry.

“We need to reform our domestic industry first and then if we can make mutual benefits with our trading partner in some specific products, then we can open our markets,” he said.

And while he accepts an FTA would benefit big exporters such as Samsung and Hyundai, Nam sees little benefits trickling down to the average person.

“The benefits they can get from exporting are not shared by the general public. Last year, I heard that Samsung made extra record profit but I haven’t heard any news that the ordinary people can have benefits from Samsung’s profit.”

By John Power

(

john.power@heraldcorp.com)

Readers’ voice

On overeducation ...

From my experiences with Koreans during my stay in Korea, I think there is no problem at all with education or studying English. Education is very important, but it depends on how one is being educated.

Education can sometimes be negative, such as brainwashing and causing one to be narrow minded. One thing that I despised about the education in Korea was the strong anti-Japanese sentiment there is, even in elementary school children. It’s okay to learn about history, but to hate is another thing.

When one goes to church, temple, mosque or other places of worship, it is to learn morals and be ethically right. We are taught to be good human beings, but at the same time, if one is to hate, it’s useless even going to our religious gatherings.

During my stay in Korea, I experienced a huge dust storm that I never encountered before. When I asked the locals about it, they said the storm was from Korea’s neighboring country, China. I was extremely shocked at how the entire Korean Peninsula suffered an environmental hazard from another country.

Instead of having so much hate and anger in Korea’s educational system, more energy and time can be used to educate Koreans on the environment and how to work with neighboring countries to solve these problems. The cleaner a country is, the more developed and advanced one can say it is. As it is the beginning of a new year, we should reconsider our way of thinking and work on making ourselves and country better. Having hate will get us nowhere no matter what. It’s a waste of time and energy.

No country is 100 percent, but we can learn from each other and see the areas where we can improve on. For example, in my experience, I can say that Korea is rich in culture such as having its own cuisine, language, traditional dress, architecture and so on. But there are other areas that Korea should work on, such as driving conditions, littering and sanitation.

The way Koreans drive is too dangerous. One can see driving in Korea ignoring red lights and not stopping for pedestrians when they are walking on crosswalks. I was shocked to see that there was no action being taken at all for this.

Also, people of all ages can be seen littering. Litter needs to be properly disposed of and not carelessly thrown anywhere. There are so many demonstrations and violence sometimes that I wonder if it’s really worth doing it. Why not spend that energy and make a country better. It’s the smallest things that can cause a big problem. We should keep our air, land and waterways clean. Work with neighboring China and have trees planted to prevent the huge dust storm that blankets the Korean peninsula. Proper education is important and it’s okay if one is overeducated, but it has to be the “right” type of education.

― Paul Stevens, Gwangju

Higher education in Korea is too accessible, not practical and is overly democratic.

Not every person in an economy needs an advanced education. In the past most people could not afford an advanced education, that being the case, acquiring one was somewhat of a golden ticket to success.

As higher education attainment has become the norm, the value of that education as similarly decreased. While a rise in the general education level of a population as a whole may be ideologically preferable in some ways, in terms of economics, if job opportunities offered by the economy simply do not require higher levels of education, then underemployment and discontent are the logical results.

Unfortunately, accessible does not exactly mean that it is practical or affordable, and students are going into more and more debt acquiring educations which are not needed by the economy. This debt can become systemic, as it appears to have become in the U.S., and lead to negative economic consequences for the nation as a whole.

In terms of practicality, students who have difficulty obtaining the jobs for which they feel they are entitled often make the mistake of continuing their educations, incurring more debt, in order to make themselves more attractive applicants. If they chose less ideal positions and gained practical experience while reducing their debt, rather than increasing their burdens and expectations, they might find themselves to both more attractive applicants as well as less economically burdened.

In terms of being overly democratic, the Korean education system as a whole seems to be based upon a one size fits all mentality, with the goal being higher education, ostensibly for all. Little emphasis seems to be placed economic realities or on aptitude based on personality or intelligence.

Students are not offered many viable options for educations which prepare them for jobs which do not require extensive academic education. Again, the idea that every student can and should obtain the highest level of academic achievement possible seems laudable, not every student is an honors student and not every student actually wants or can realistically expect to become a CEO or a doctor or a patent lawyer.

― Chris Karoly, Seongnam

On welfare ...

In recent times, “Free Welfare” has become a major issue in society. The greater attention to welfare indicates our status as one of the more advanced countries in the world. Obviously, this is very welcome.

However, excessive spending on welfare is causing real headaches in Europe. These conflicting results are confusing, and it is hard to judge whether more welfare will be always be a good thing for our community. The welfare policy in Europe ― giving everything for nothing ― has proved a failure. So what should South Korea’s welfare policy be?

The answer lies in micro credit, which has been conducted in South Korea since 2008.

Micro credit is a system of small loans, providing capital to start businesses and operating funds, aimed at poor people without access to finance. It is reminiscent of the old adage ― not giving out fish but giving out the means to catch fish.

In terms of providing neglected social groups with a chance to seek a living through work, micro credit is one of the most productive welfare policies this community can pursue.

That being said, after reviewing the recent government audit of micro credit, many problems have arisen, such as corruption by senior officials, misappropriation, bribery, over-lending to people with low credit ratings, vehicle mortgages in spite of being unsecured loans and so on.

In order to solve above mentioned problems, promoting transparency in micro credit businesses should be a priority. We need a well constructed system of internal audit.

There are also problems with the lending requirements. For example, if you want a loan for your business of up to 20 million won, your capital ratio has to be more than 30 percent. If you want more than that, your capital ratio must be at least 50 percent.

Everyone knows that this requirement is unrealistic for lending to people who are rejected by banks. Such stringent conditions can be counter-productive since they defeat the very purpose of micro credit and will reduce demand for micro loans.

Besides, funding could be a problem in the near future. Experts warn that the equity investments and dormant deposits are not sufficient to satisfy all the demands of people who need micro credit.

Therefore, to ensure the long-term success of the scheme, there is an urgent need to raise the necessary capital stably.

Finally, we must also promote the importance of micro credit. We have to change the negative perception of the loans. It is essential to assure people that micro credit is not directly linked to corruption and that it can change your life for the better.

It is surprising that the foundation of micro credit supported 490 billion won to 85,000 people in 2011.

Micro credit experts across the world say that the system in Korea is well constructed. Now it is up to our efforts to make it better and more useful, for creating both interest and the common good.

Who knows, South Korea could achieve another “miracle on the Han” by creating a successful welfare model where European countries have failed!

― Lee Eun-woo, Daewon Language High School, Seoul

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)