After decades of rapid change ...

Is Korea looking after its cultural heritage?

Threats to Korea’s history

As has been the case in many countries, Korea’s cultural heritage has faced numerous threats in both ancient and modern times. Japanese colonization and invasions by other foreign powers saw thousands of artifacts taken from the country, many of which have never been returned. It is estimated that 74,434 artifacts remain overseas, 46 percent of which are in Japan.

In recent decades, rapid modernization has also had implications for the preservation of traditional Korea culture. New development has seen the destruction of “hanok,” the country’s traditional houses, in Seoul’s Gahoe-dong and other districts. Ancient traditions such as shamanism and craft making have also felt the impact of such change. Fears that “ssitgimgut,” a rite to summon the spirits of the dead that is native to Jindo, an island off Jeolla Province, could be in danger of extinction has led to efforts to have it recognized by UNESCO. Similar efforts undertaken to petition UNESCO in the past have been successful, with “pansori,” a form of traditional music, and Gangneung Danoje Festival now recognized as Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

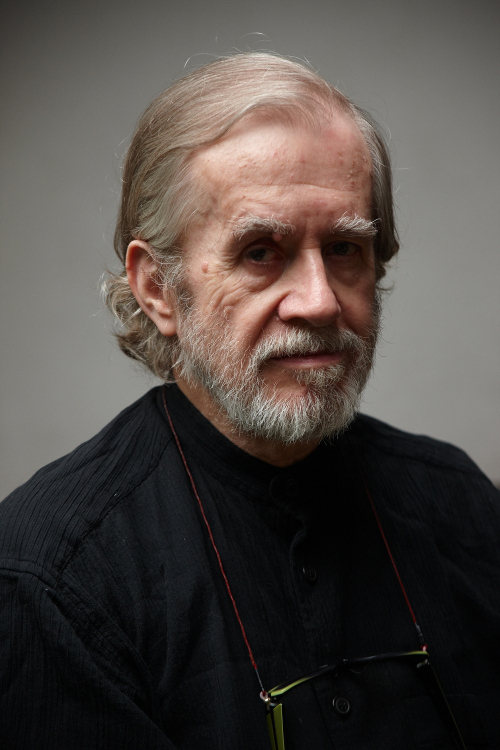

|

The former residence of poet Han Yong-un in Seongbuk-dong, Seoul (Yonhap News) |

More to do, but a lot done

The answer is: In a way, yes, but it could be better and is in need of some improvement.

For example, the return of 297 books of the Uigwe (royal Joseon Dynasty protocol texts) from France was an improvement, but this should not be merely on a five-year loan basis as has been negotiated.

The Uigwe, UNESCO designated cultural assets, should have been returned for good as part of Korea’s cultural heritage. Another good example is the folk song Arirang. In an article entitled “Korea seeks UNESCO listing for ‘Arirang’ to thwart China’s claim,” dated June 24, Culture Minister Choung Byoung-gug said: “Korea plans to apply for a UNESCO designation for the nation’s folksong ‘Arirang,’ in all its regional forms, in hopes of making it an intangible world heritage by the end of this year.”

Choung’s comments followed China’s recent decision to list the song, as well as other cultural practices of ethnic Koreans living in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in Jilin Province, Northeast China, as its own National Intangible Cultural Assets.

The Korean government in 2008 filed an application for a UNESCO designation for “Jeongseon Arirang,” the original form of the folk song, but later decided to apply for all regional versions.

Choung said he did not plan to negotiate with China regarding the UNESCO application for the song.

Kim In-kyu, senior researcher of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Division of Cultural Heritage Administration, said that once designated, “Arirang” could be internationally recognized as Korean heritage.

This year, the Natural Folk Arts Festival celebrated its 52nd year. However, it has received no coverage, except for TV listings, in the English-language press since 1959, and Korean language coverage has also been minimal. Arirang has been sung in all variations at practically every performance, but an application to UNESCO was never made until the Chinese threat loomed.

In a preface to the publication of “Korean Folk Arts ― A 33-Year History of the National Folk Arts Festival,” published in 1992, former minister of culture Yi Su-jong said “regional folk culture is the root of the nation’s culture.”

In this regard, following 36 years (1910-45) of so-called “cultural cleansing” by the Japanese colonialists who feared that Korean folk culture would foment a desire for national unity, and in the aftermath of the Korean War (1950-53), the country was caught up in a desperate rush to rise once again, like the phoenix, from the ashes of destruction, re-build its infrastructure, and recover from severe economic deprivation.

At that time, in its effort to Westernize, modernize, and industrialize, the government instituted the Saemaul (New-Village) Movement, in which the people were urged to do away with the past and think only about becoming an advanced, prosperous nation. But, in the process of doing so, they came precariously close to losing their cultural heritage. The sound of farmers singing in the fields as they labored could no longer be heard over the din of tractors; the rowing chants of fishermen could no longer be heard over the whir of motor boats; and the songs of grandmothers weaving could not be heard over the noise of a sewing machine. Added to this problem, young people were leaving the farms in ever-increasing numbers to seek better-paying jobs in the factories that sprouted up in all over the country. The aging rural population was dying out, leaving no one to pass on the traditional songs they once sung.

The advent of the radio and TV that spread to almost every farmhouse also contributed to the problem by constantly broadcasting Western and Japanese-style pop songs.

Alarmed at the rapid disappearance of traditional folk culture, folklorists and ethnologists urged the government to take action before it was too late. And so, in 1958, the first National Folk Arts Contest, now called the “Folk Arts Festival,” was born.

At the outset, this annual October fete was held only in Seoul, and the number of participants was small. But, later on, as it was staged in different provincial cities around the countryside, the number of participating teams increased year by year to a total of more than 250 folk plays, mask dance-dramas, farmers’ songs and music, and other genres, many of which have since been designated “Intangible Cultural Properties.”

Void of historical records and musical scores, this indeed was a very good thing because it encouraged middle-aged people and youngsters living on farms and in fishing villages to re-enact the folk plays, mask dance-dramas, and farmers and fishermen songs that existed only in the memory of village elders who were often too aged or infirm to perform; and, as is common knowledge, once a tradition is lost, it is usually impossible or extremely difficult to recreate again.

Concurrent with the 2004 festival was the 20th General Conference and 21st General Assembly of the International Council of Museums held in Seoul from Oct. 2-8 to review the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the safe-guarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage. With the fast disappearance of this heritage in the face of globalization, UNESCO, in the 1990s, initiated a movement for its protection and preservation, and established the “Proclamation of Masterpieces of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity” in 1998.

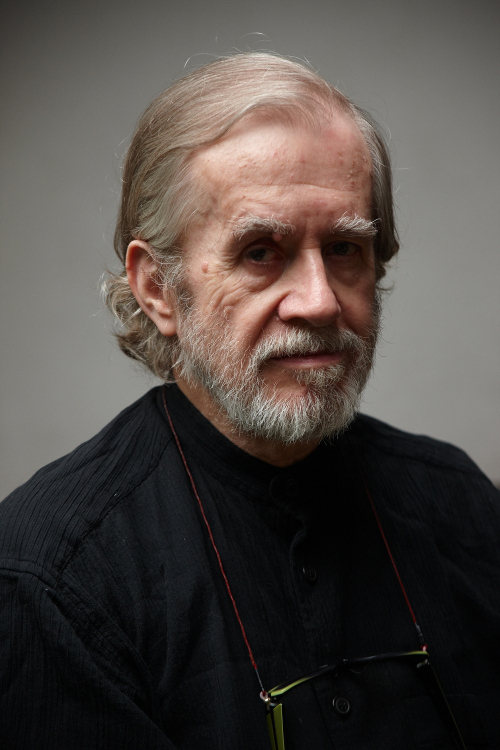

|

Alan C. Heyman |

By Alan C. Heyman

Alan C. Heyman is an author, translator and traditional Korean musician who has lived in South Korea for more than 50 years. He has received a number of awards from UNESCO and the president and prime minister of Korea for his work to promote Korean cultural heritage. ― Ed.

South Korea neglects its heritage

A few years ago, I attempted to buy a newly made traditional Korean horse-hair hat, or gat. Together with my wife, I visited several places that make hanbok for advice, but with no luck. Eventually, we were told that my goal was no longer possible because the last master of the craft had died. All we could find were plastic imitations, made in China. What a sad end for such an accomplished art.

Yet it is not inevitable that traditional arts and crafts should perish. Indeed, they can flourish and meet needs in the modern world. One need only look to France, where two of the world’s leading luxury brands, Louis Vuitton and Hermes, have helped keep alive a French tradition of excellence in leatherwork. The Venetian island of Murano also excels today in handmade glassware, just as it did in the 13th century.

In my home country, England, many traditional crafts died in the 19th century as the country changed from a traditional agricultural to an industrial society. Yet today in the U.K. and across Europe, there are successful projects to encourage and sustain traditional arts and crafts. Against the background of increasing uniformity that globalisation encourages, local and regional traditions helps foster the cultural bonds that bind communities together and create a sense of identity. They also play a key role in the leisure, recreation, construction and tourism industries creating economic as well as social values.

Industrialization has been underway in South Korea for only the last 50 years. Though many traditional arts and craft still survive, they face an uncertain future. A 2006 survey by the JoongAng Ilbo, found that almost half of Korean craftsmen designated as “intangible cultural assets” predicted their skills would die with them.

When both craftsmen and their crafts pass away, the heritage of buildings can provide a tangible manifestation of a society’s history, past ways of life, crafts, technologies and their cultural context. However, despite their cultural value, buildings and monuments from the past are all too easily destroyed and can never be re-created. Unfortunately, there is little understanding in Korea of the care and precautions needed to ensure that future generations can continue to enjoy and learn from those old buildings that have survived through history.

Recent newspaper stories of rainfall damage to Dongdaemun, National Treasure No. 1, carried a sad echo of the destruction of Namdaemun in 2008. According to this newspaper, no maintenance work on Dongdaemun’s 14th-century wooden gateway had been completed since 2000. Namdaemun, a World Heritage Site (and also National Treasure No. 1 till its destruction), might have survived arson attack had there been fire alarms, sprinklers, a security system, or guards ― all of which were reportedly lacking. Extreme weather and vandalism are two of the ills of modern times; each poses enough danger to warrant taking precautions, especially for the nation’s most valued treasures.

Sadly, there are more examples of damage to major heritage buildings in recent years. Last December, fire also destroyed the 1,300-year-old Cheonwangmun, a major wooden structure at Busan’s Beomeo Temple. Another World Heritage Site, Hwaseong Fortress, has also been damaged by fire.

A more insidious erosion of Korea’s heritage has taken place in Bukchon, described as a protection area as Seoul’s last hanok village. Since 1985, the number of hanoks in Bukchon has fallen from 1,518 to less than 800. The character of the district has also changed from one where hanoks were the majority of the buildings to one where they are a declining minority. Government projects, such as erecting the Constitutional Court and re-development permissions to chaebol caused the major losses. More recently, Seoul City’s Bukchon Plan designed to restore and preserve many of the hanoks instead resulted in their demolition and replacement with modern concrete buildings. While talking about protection and preservation for over 20 years, successive governments have presided of policies of destruction.

Across the entire spectrum of Korea’s cultural heritage it is clear that the government does too little to preserve the legacy from the past. Moreover, what little the government does attempt is poorly planned, counterproductive, or simply ineffective. Among advanced countries, South Korea is uniquely negligent about safeguarding its own cultural heritage.

|

David Kilburn |

By David Kilburn

David Kilburn is an activist for the preservation of hanok and a former journalist. ― Ed.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)