Skyhigh sell-off

The President Lee Myung-bak administration proposed a partial privatization of Incheon International Airport in 2008 with a plan to sell off a 49 percent stake, including 15 percent to a foreign airport operator. Lee said the move would improve the competitiveness and efficiency of the country’s main gateway. The plan was ultimately shelved in the face of public antipathy. Last year, the Grand National Party drew up a bill for a similar plan, only to see it stalled indefinitely at the National Assembly.

The issue was put back on the agenda yet again in August when GNP Chairman Hong Joon-pyo proposed selling a 49 percent share of the airport to low-income citizens at below market value. Following Hong’s suggestion, the government decided to go ahead with a more modest plan: A 15 percent stake would be sold, to Koreans only, at a discounted rate. Opposition parties and left-leaning civic groups have fought against moves to privatize Incheon to any degree. They say that arguments about improved management and efficacy fall flat when the airport has already been rated the world’s best six years in a row. They also argue that a private operator would inevitably hike fees to boost profits, hindering citizens’ access to what should be a public service.

|

A terminal at Incheon International Airport. (Yonhap News) |

The trend is toward privatization

The plan to sell a stake in Incheon International Airport Corporation has been mired in misunderstanding from the start. In 2008 the Korean government emphasized the need to introduce advanced airport management techniques, while lacking sufficient preparation, and even mentioned the possibility of selling a stake to foreign capital. Coincidently, a rumor was leaked about an undertaking by Australian financial group Macquarie. No citizen would agree with selling a stake in the national airport with abundant growth potential to foreigners. The plan was halted thanks to natural nationwide opposition.

The privatization of IIAC has been planned since the governments of Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun. However, the first attempt of the incumbent government regretfully caused the plan to lose credibility. The privatization of the aviation industry is already an international trend. Most government-owned airlines representing national prestige have been privatized. The participation of private capital in gateway airports is also very active around the world. Thirty-five out of the 50 largest airports in the world have either been sold or are planning to sell a stake or management rights. This is an almost universal market phenomenon that aims to secure investment capital, management efficiency and facilitate collaboration of capital.

It is distressing to see serious misunderstandings in this debate. It is questionable whether the argument against privatization itself has any value. First of all, some argue that the privatization of airports has never succeeded. Wrong. Full privatization of ownership as well as management rights at Heathrow Airport and Sydney Airport resulted in passive investment and airport fee increases. But most international airports such as Frankfurt, Zurich, Schiphol and Charles de Gaulle have shown positive results through partial privatization.

Even Beijing Airport in China is 43 percent privately owned.

Secondly, there’s the argument that national wealth will be lost once the airport is sold to foreign capital. This is a misunderstanding. The essential part of the amendment of IIAC regulations is that the government maintains 51 percent ownership while foreign ownership is capped at less than 30 percent. This is a relatively strict limitation compared to the general share structure of state-owned companies. The Korea Electric Power Corporation has a foreign ownership limit of 40 percent. In the private sector, Samsung Electronics and POSCO, which is 50-percent foreign owned, are still Korean companies.

Third is the argument that hasty action may result in an undervalued sale. But the current situation is different to the Asian financial crisis. The brand value of IIAC is at its peak after 10 years of operation, and the domestic stock market is functioning very efficiently. In the evaluation of IIAC as No. 1 for service value, the airport brand as well as growth potential and cash flow based on future demand were already reflected. Concern about under-valuation of IIAC is an underestimation of the Korean financial market.

Fourth is the possibility of airport fees increasing. This is absolutely impossible. The landing fee that airlines pay is determined by the Korean government, which possesses a 51 percent share. Electricity prices have never been determined for profitability at KEPCO, which sold a 49 percent share in 1989.

What will be the biggest positive effect of the IIAC stake sale? Above all, market surveillance will be strengthened. Listing stocks directly means that the disclosure of business management becomes legally mandatory. Along with the general meeting of shareholders, an opportunity will be provided to evaluate transparency and management. In addition, the capital inflow from the stake sale can finance airport infrastructure such as the railroad connecting the terminal until the on-going phase 3 expansion is complete. Another positive effect will be the globalization of IIAC through capital collaboration with international airports.

The adverse criticism was caused by the representative of the ruling party when he commented on the specifics of the sale method. It became an exhaustive debate inviting opposition from minor parties. IIAC is already a global airport receiving attention from the aviation business.

IIAC is moving forward in the international market with construction and operating know-how accumulated since the opening, along with its brand as a package.

It is desirable that the government and the parliament use this opportunity to work together to find how to maximize the value of IIAC. We are in an age when the airport industry should be acknowledged as a growth industry and moved into the international market. The primary responsibility for the lack of progress lies with the government for the unnecessary debate on the sale.

The cause of the problem was the attitude of onlookers; the government didn’t give sufficient explanation of the financial preparation and or the global trend of formation of airport groups. It simply spoke about the stake sale only.

|

Hurr Hee-young |

By Hurr Hee-young

Hurr Hee-young is a professor at the department of business administration at Korea Aerospace University. ― Ed.

It should be a public service

The controversy surrounding privatization basically stems from fundamental differences regarding the extent to which the government should intervene in the economy.

The world under the regime of neo-liberalism has already moved some goods or services that are traditionally provided by the government into the private sector. This is privatization. On the other hand, along with the policy reasoning of privatization, the mix of public and private provision has changed.

During the 19th century, there was much greater private responsibility for education, police protection, libraries, sanitation and other functions than there is under neo-liberalism. Recently, the classical policies of individualism and liberalism are pervasive in Western societies.

Some important services ― called public goods ― can be obtained privately. Protection is traditionally provided by a publicly provided police force. Alternatively, to some extent, protection can also be gained by strong locks, burglar alarms and bodyguards that are privately hired. Indeed, there are now three times as many privately hired policemen in the U.S. as public ones.

As a result of budget cuts that reduce waste collections, businesspeople in several U.S. cities band together and hire their own refuse collectors to keep their streets clean. Individual homeowners contract private companies to provide protection against fires. In Demark about two-thirds of the country’s fire service is provided by a private firm.

In reality, there can be the mix of public and private provision in the above cases. However most public economists will never agree to privatization of pure public goods, known as Samuelsonian public goods.

Unlike fire protection, street cleaning and so on, pure public goods, such as national defense, have two characteristics in terms of consumption. One is that once it is provided, the additional resource cost of another user is zero. It means non-rival consumption. The other is that to prevent anyone from consuming that good is either very expensive or impossible. In contrast, private goods like academic education represent rival and excludable consumption among people.

Traditional wisdom dictates that pure public goods like national defense should be provided by the government. The individual benefit from consuming national defense is security obtained by national protection of his or her life and property against violent outside intruders.

Likewise, the basic benefit that an airport gives its customers is their security. Airport security has become a major object of concern after Sept. 11, 2001. While there was a consensus that the U.S. security system had totally failed and had to be upgraded, there was a debate on how to accomplish this.

Some argued that airport workers, including security employees, should be federalized (nationalized); that is, they should be employees of the federal government. Others argued that while the government should pay for airport security, it would best be left to private firms which would be monitored and held accountable for mistakes.

This debate highlights the issue over whether privatizing Incheon airport would be a bad idea. It also highlights the divide between governmental provision of airport services and productivity. In this light, customers mostly agree that airport security should be provided by the public sector, but still disagree over whether other airport services should be produced publicly.

The disagreement over the issue of provision of airport services is usually a debate about efficiency. For example, all other things being equal, the input costs of airport services by the private firm are lower. But lower wages in a private firm result from employing irregular and inexpensive workers. Furthermore, opponents of privatization respond that these examples of lower relative wages at private firms overstate the cost savings of private production. In fact, there is surprisingly little systematic evidence of the cost differences between private and public production.

An important reason for this is that the “quality” of the services provided in the two modes may be different, which makes comparisons difficult. Perhaps, for example, private airports have lower costs than their public counterparts because the former can refuse to admit passengers or go without expensive security measures. This brings us to the central argument of opponents of private production.

A possible response to this criticism is that the government can simply write a contract with the private security service that the government wants. However, those who believe that airport security should be publicly produced argue that it is impossible to write a contract to cover all eventualities and that private firms would skimp on training workers to increase profit. Here, we have to point to the U.S. system in place on Sept. 11, 2011, in which airport security was funded by airlines and security personnel received low pay and little training.

An additional criticism was that privatization would mean different airports having different levels of security to match the tastes of passengers. Ultimately, the debate on whether privatizing an airport would be a bad idea was won by those who favored public production of airport security. Since 2001, airport security has been put under the supervision of a new federal agency, the Transportation Security Administration, and security personnel are members of the federal workforce. The above story must be applied in Korea, at Incheon airport.

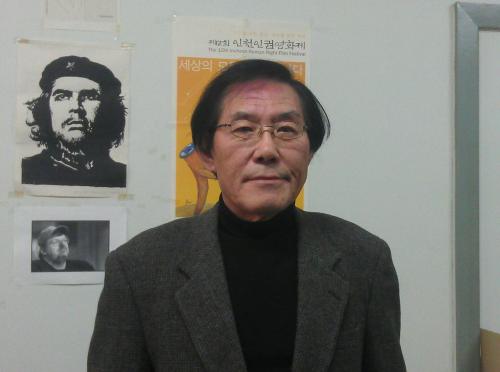

|

Kim Young-Q |

By Kim Young-Q

Kim Young-Q is a professor of public administration at Inha University in Incheon. ― Ed.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)