|

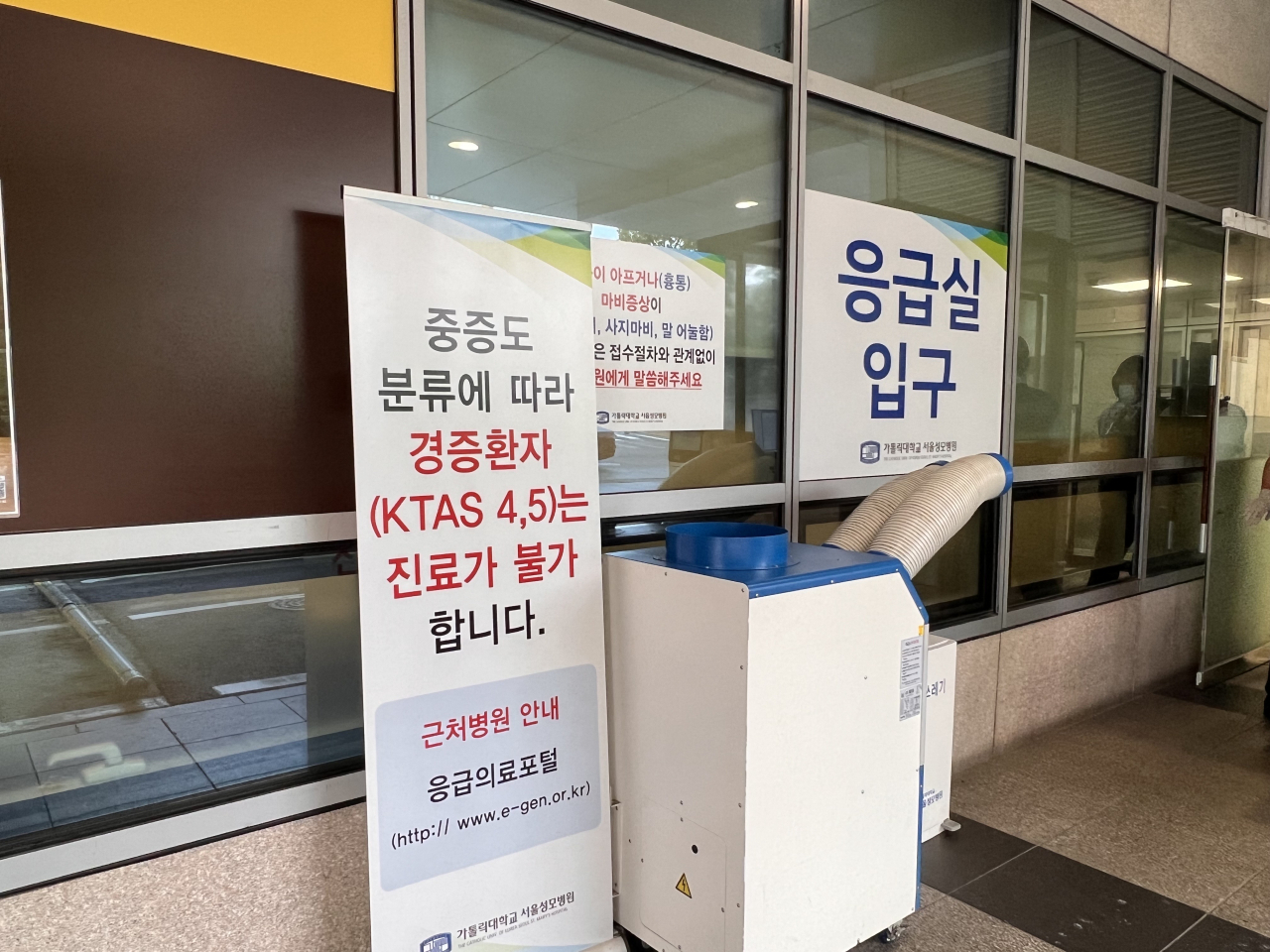

A banner notifying that patients in levels four and five -- less urgent and non-urgent -- in the Korean Triage and Acuity Scale cannot get treatment is set up in front of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital's emergency center. (Park Jun-hee/The Korea Herald) |

Last month, 33-year-old office worker Kim A-young experienced a nightmare when a first responder refused to take her to the emergency room despite her severe stomach pain.

"I was informed that ERs at university hospitals wouldn't accept patients with stomach pain, which was later diagnosed as acute appendicitis," she said. "I was taken to a nearby community hospital but couldn't have the surgery immediately. Although the doctor indicated that my case was severe, I had to wait another day for surgery because their only surgeon was also away for the day."

Though Kim was not in a life or death situation, growing reports of patients in extreme cases being rejected from ERs have stirred nationwide concern.

Currently, South Korean ERs are focusing exclusively on critically ill patients requiring urgent care, and are unable to admit those with conditions like a ruptured appendix or severe abdominal pain as they once did before the medical standoff started off in February.

A 28-month-old baby has been in a coma for a month after being refused admission by 11 emergency rooms, while a national veteran patient showing gastrointestinal bleeding reportedly died after being rejected for treatment at the Veterans Health Service Medical Center's emergency room, according to reports.

This shift in ER operations stems from the absence of the residents and interns who left hospitals in protest against the government's plan to expand medical school quotas. Medical professors, who also serve as teaching physicians, have been taking turns handling emergency cases. However, with the growing medical void and fatigue among remaining doctors, hospitals are now prioritizing patients at levels one through three on the Korean Triage and Acuity Scale (KTAS), while denying treatment to those at levels four and five. Acute appendicitis is classified as level four unless it is ruptured.

Hospitals, for their part, say that they cannot help but reject patients as they grapple with staffing shortages; there aren't enough physicians in other medical departments to provide follow-up care or hospitalize patients after they receive initial care in the emergency room. In some places, physicians from other departments are working in ERs to fill in the vacancies, according to the Health Ministry.

Public anxiety is mounting over potential further interruptions during the Chuseok holiday, when many hospitals, except for ERs, are closed. Amid these concerns, the medical community and the government are at odds over the sustainability of emergency rooms, each accusing the other of failing to acknowledge the true state of ER operations.

In a radio interview with broadcaster SBS on Monday, Health Minister Cho Kyoo-hong said the issues over long ER lines and patients being declined treatment "extend beyond emergency rooms" to follow-up treatments, which were present even before the walkout by the medical community, stressing the problem could be addressed through medical reform.

The Health Ministry added that the number of doctors, including junior doctors and physicians, working in emergency rooms is 73.4 percent of the "usual capacity." Out of the 409 emergency rooms nationwide, 406 are "maintaining 24-hour operations," although 27 have reduced the number of beds.

In addition, authorities said it would deploy 15 military physicians to emergency rooms operating under limited conditions on Wednesday to cope with emergency care before and after the Chuseok holiday from Sept. 14-18. They will be placed at Ewha Womans University Medical Center, Ajou University Hospital, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Chungnam National University Sejong Hospital and Kangwon National University Hospital.

The decision comes after the government last week designated the holiday period as "Chuseok Holiday Emergency Response Week" to prevent emergency rooms from becoming overloaded and ensure that patients can get treatment.

In stark contrast, the Korean Medical Association -- the largest doctors' group here -- lambasted the government for "denying the current crisis in emergency care" and "worsening the situation with short-sighted measures."

"As long as the lights are on and signs are up, it doesn't mean an emergency room is open. It is open only when it is a place where emergency patients can receive treatment," the KMA said.

The Medical Professors Association of Korea echoed that medical professors and physicians filling the medical void "cannot bear the situation anymore" due to extreme exhaustion, criticizing the government for "ignoring the reality."

"(We) worry that understaffed emergency departments outside of Seoul struggling with a lack of resources might not even make it through September," Professor Ko Beom-seok at Asan Medical Center, who heads the public relations committee of the emergency committee of medical school professors, told The Korea Herald.

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Health and care] Getting cancer young: Why cancer isn’t just an older person’s battle](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050043_0.jpg)