|

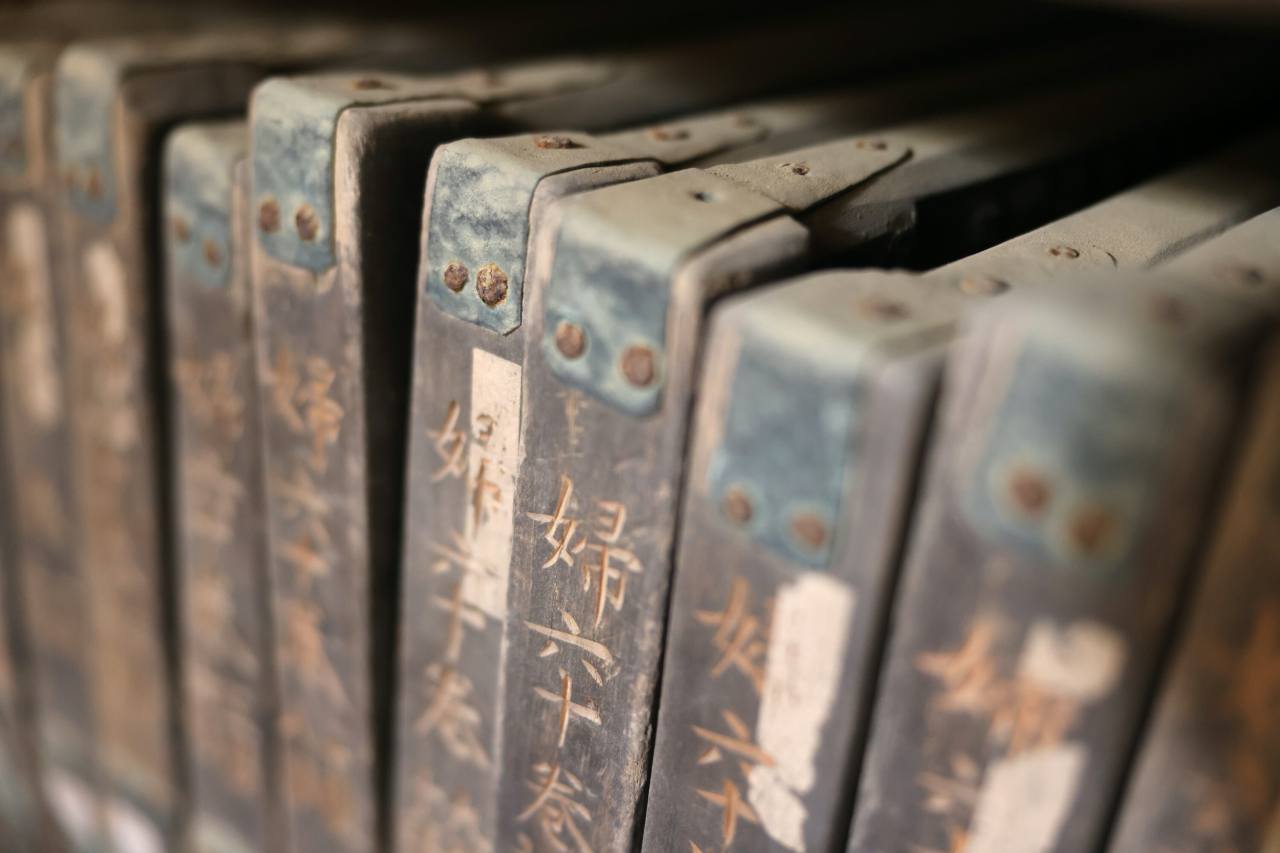

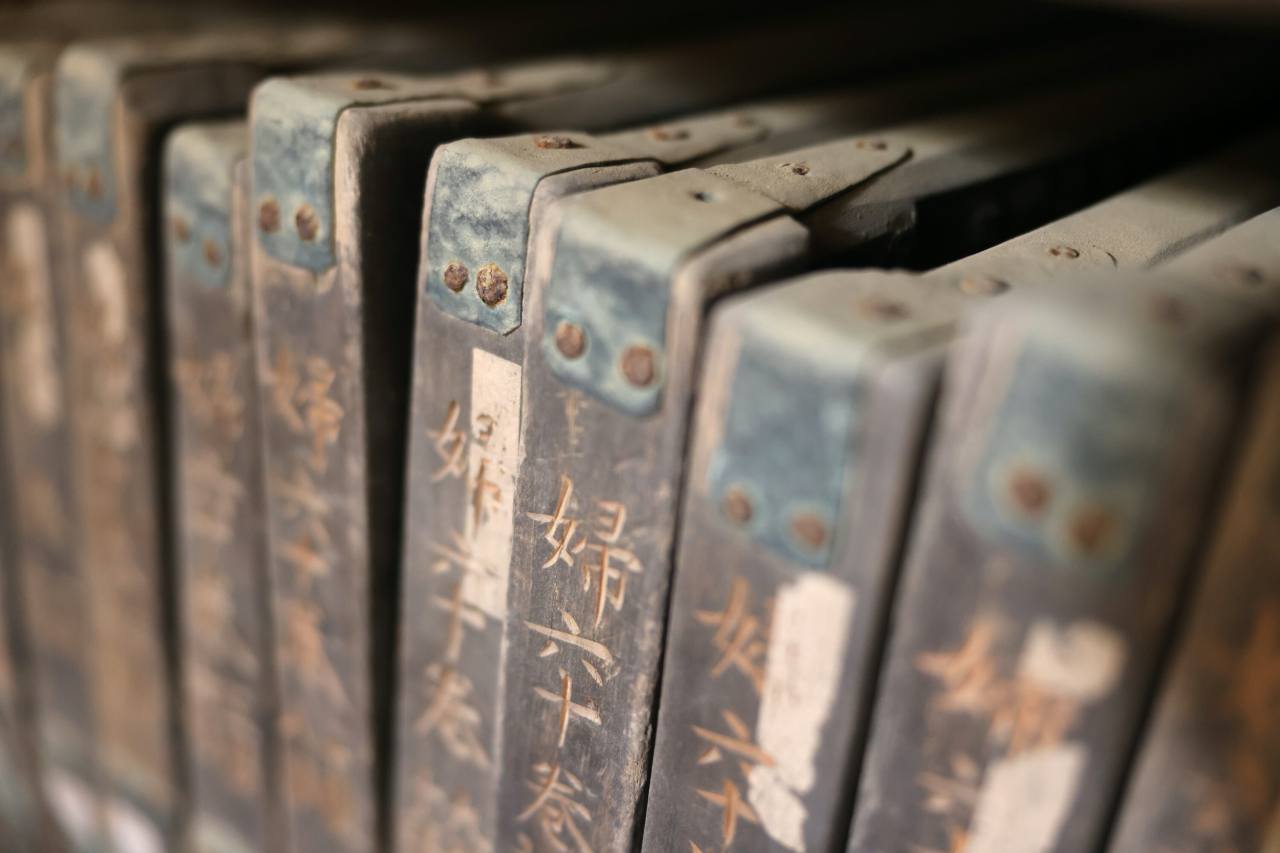

The 81,352 Palman Daejanggyeong printing blocks withstood centuries of weather and harsh elements without modern temperature and moisture controls or heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems with its scientific building design. Photo © 2021 Hyungwon Kang |

|

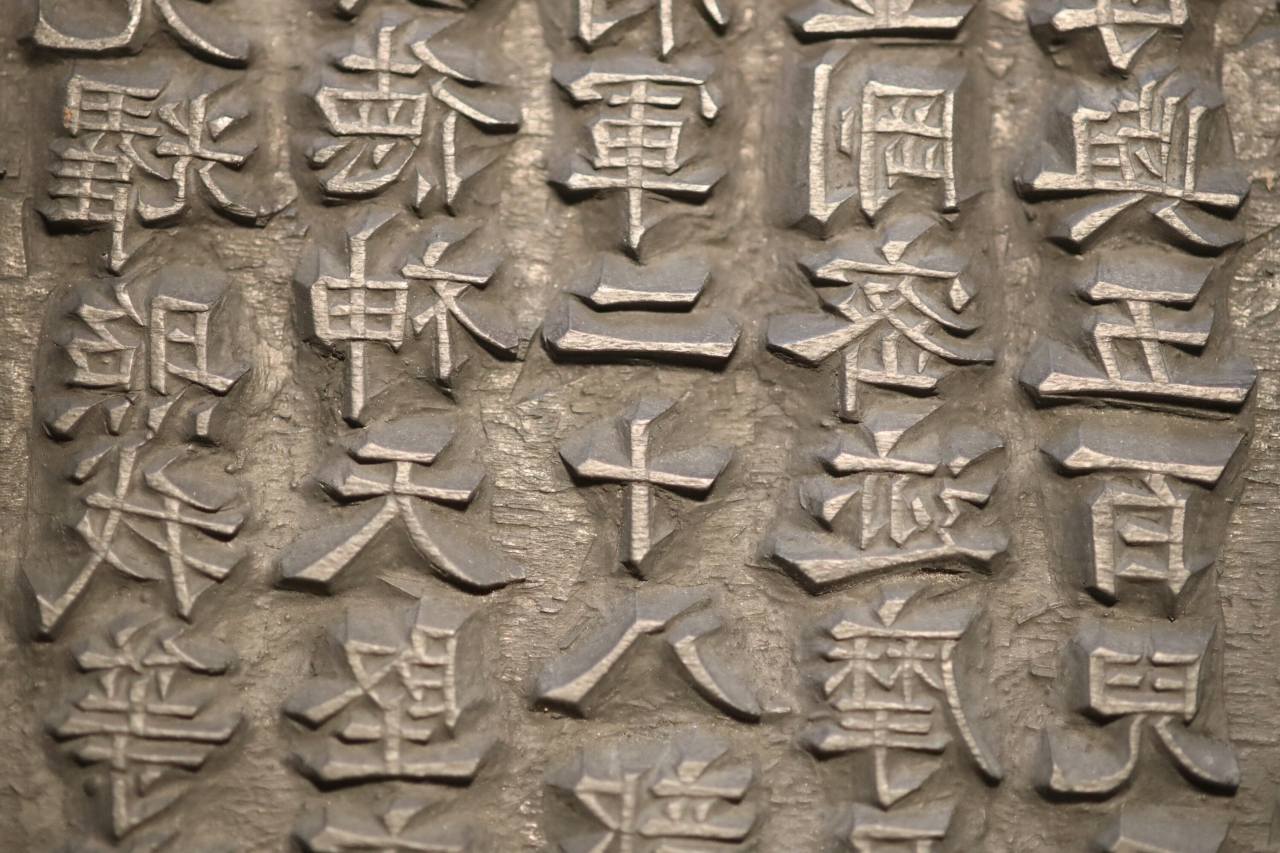

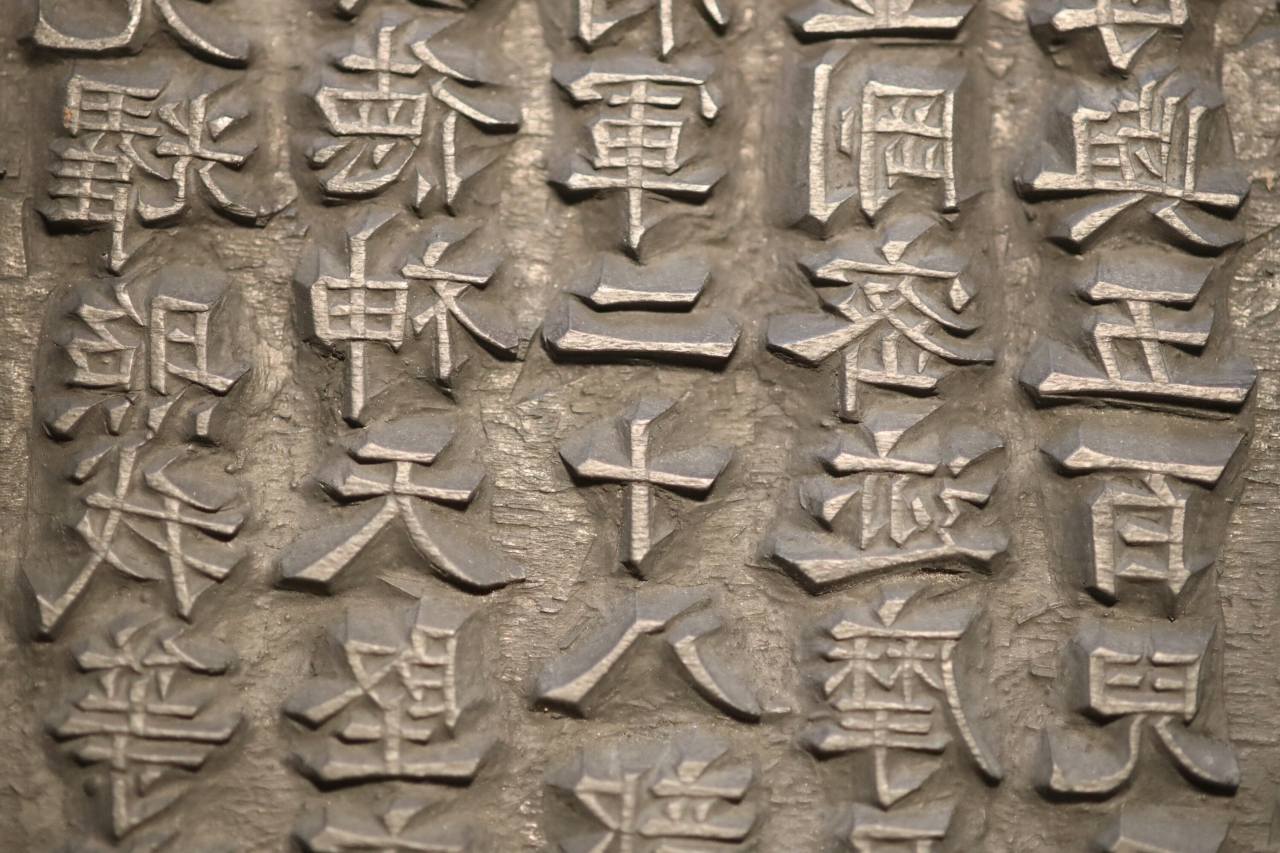

A close-up photograph of the Palman Daejanggyeong printing blocks reveals almost metal-like wooden Hanja character fonts looking laser sharp even after more than 700 years. Photo © 2021 Hyungwon Kang |

No civilization accomplished documenting all-known Buddhist thought as the Goryeo Kingdom did, some seven centuries ago during a time of war and a clash of empires.

Written Hanja, along with Buddhism and Confucianism, have been steadily developing in Korean culture since before the common era.

Along with indigenous beliefs and Confucianism thoughts, Buddhism became the most entrenched religion for Koreans from early on.

One of mankind’s great innovations in history is the invention of printing, and Koreans completed it by printing on “hanji,” paper made from the inner bark of the mulberry tree.

Printing enabled the proliferation of knowledge that was previously the exclusive domain of literate scholars.

While Genghis Khan’s grandsons were terrorizing and destroying Eurasian kingdoms and villages, they were not so successful in conquering the Goryeo Kingdom on the Korean Peninsula in the 13th century.

The Mongol-Goryeo war and resistance lasted some 40 years, from 1231 to 1270, with the Goryeo people putting up a fierce and seemingly impossible resistance while the royal family made periodic concessions and denied outright victory to the Mongols from the island fortress of Ganghwado -- part of present-day Incheon -- away from Mongols on horseback who were inept at naval warfare.

During the second Mongol invasion in 1232, the 6,000-volume, the First Tripitaka Koreana wooden printing blocks, which were carved in early 12th century, were burned at the Buinsa Buddhist temple in Daegu by nomadic Mongols.

The Goryeo people responded to that tragic cultural and religious loss with a 15-year project (1236 to 1251) to carve the Tripitaka Koreana, an incredible set of more than 81,000 wooden printing blocks.

|

The Ven. Eunggi holds up a Palman Daejanggyeong printing block at Haeinsa’s Janggyeong Panjeon, the depository for the Tripitaka Koreana. Photo © 2021 Hyungwon Kang |

|

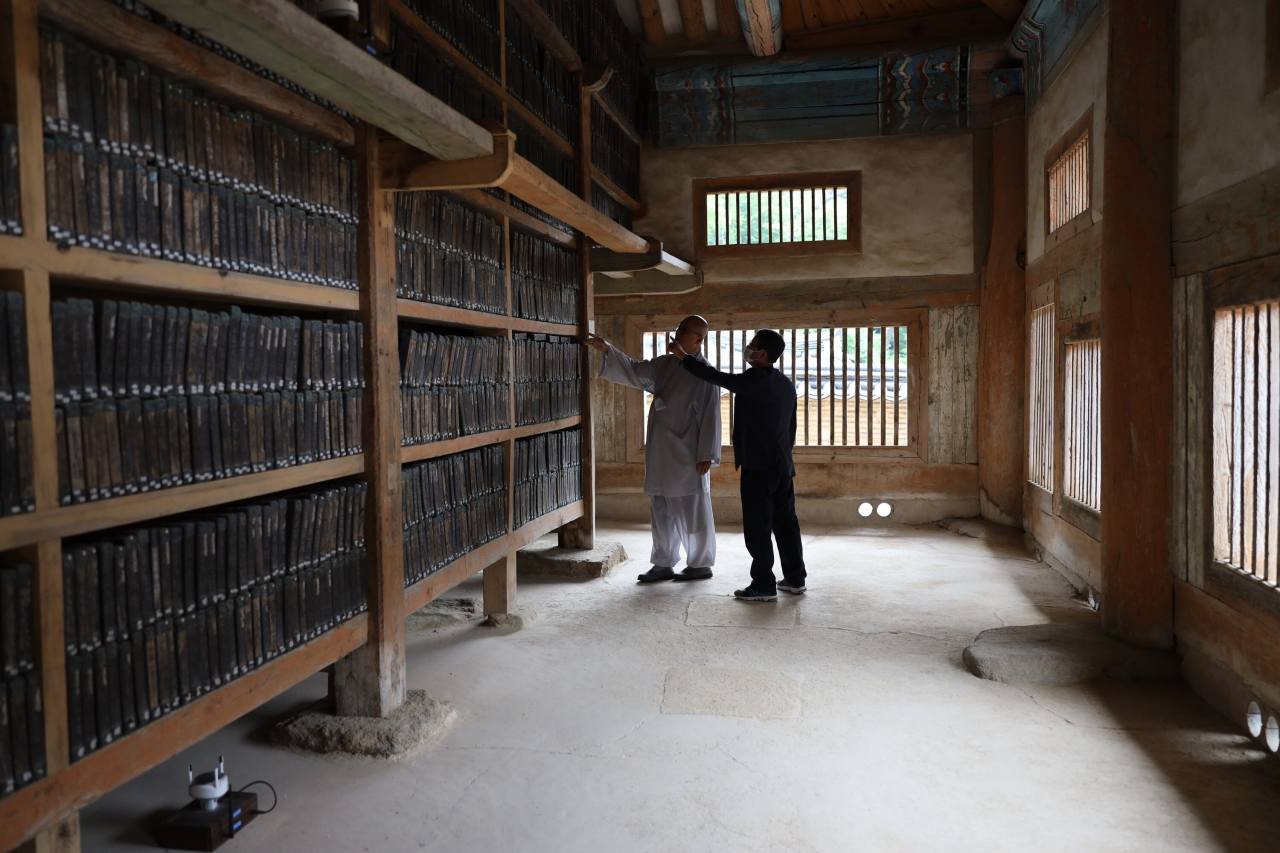

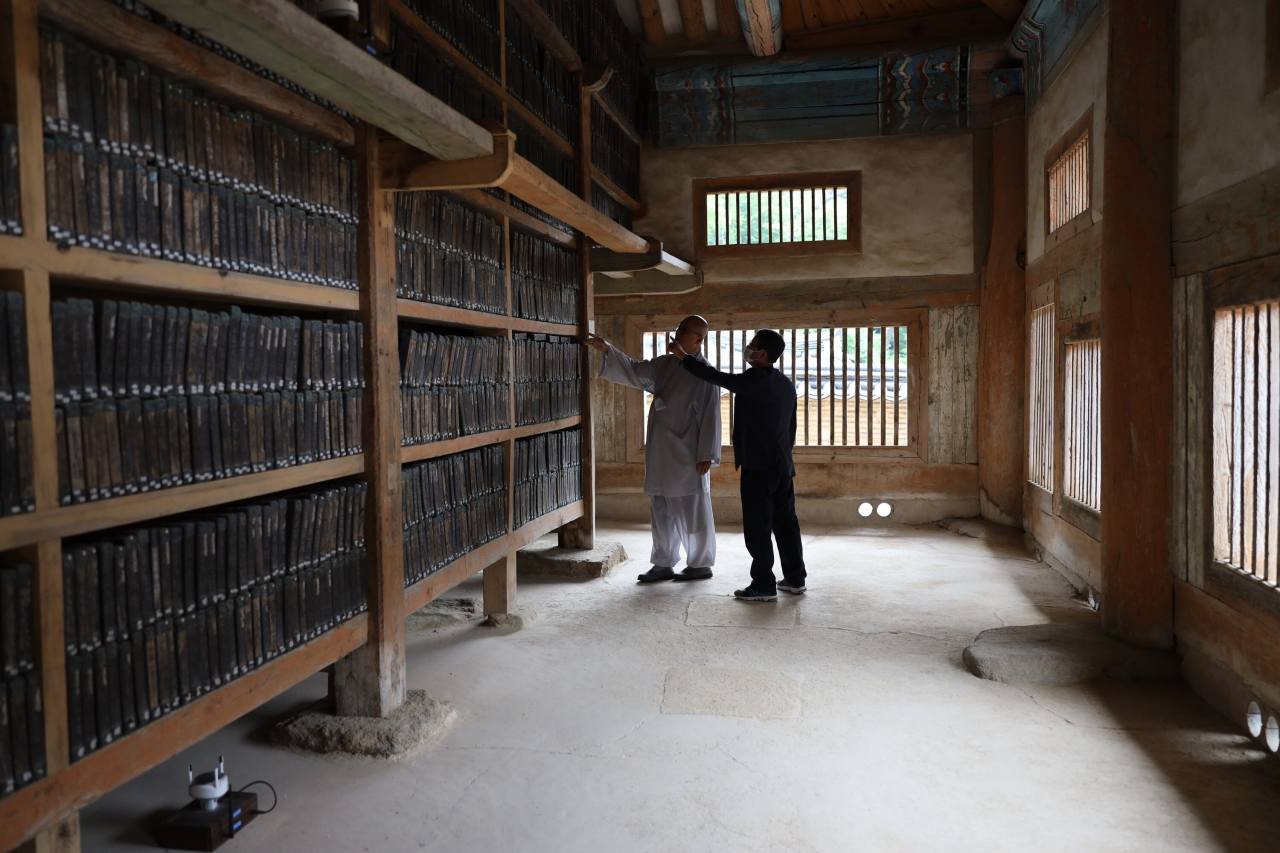

The Ven. Eunggi and Nam Kwon-hee, a preeminent authority in ancient printing and Goryeo movable metal type printing, inspect Palman Daejanggyeong printing blocks at Haeinsa’s Janggyeong Panjeon, the depository for the Tripitaka Korea. Photo © 2021 Hyungwon Kang |

While Korea was head and shoulders above the rest in inventing metal printing types during the early 13th century, the Goryeo people had also perfected woodblock printing with an incredible carving of more than 52 million characters in Palman Daejanggyeong, which means 80,000 Tripitaka.

Tripitaka refers to the three categories of Buddhism teaching: scriptures, rules and Buddha’s own words, and Palman Daejanggyeong meticulously chronicles them all in a whopping set of 52,330,152 Hanja characters carved on both sides of the 81,352 wooden printing blocks.

The Palman Daejanggyeong is a collection of all known Buddhist knowledge up until the 13th century and the most comprehensive encyclopedic collection of Buddhism studies today. One could spend a lifetime studying it and may not be able to absorb all the knowledge engraved into the incredible set of wooden printing blocks.

The task of carving 52 million Hanja characters on 81,000 wooden printing blocks in and of itself would have been a challenging project

Buddhism was the national religion of the Goryeo Kingdom, and indeed it was with Buddhist faith that the Goryeo people met the divine challenge and completed the carving of Palman Daejanggyeong during a time of war.

Each of the Palman Daejanggyeong printing blocks measures in the range of 68 to 78 centimeters in width, 24 centimeters in height and 2.7 to 3.3 centimeters in thickness.

Sargent’s cherry (Prunus sargentii) and wild pear (Pyrus pyrifolia) trees were used to make the wooden blocks. The lumber was naturally treated through a process that involved approximately three years of soaking them in sea water, dipping them in boiling saline water and slowly drying them to prevent warping or cracking of the wooden boards.

Recent inspection and close-up photography of the Palman Daejanggyeong printing blocks reveal the almost metallic quality wooden types carved on a flat wooden board, some showing a lacquer stain finish. Lacquer, made from the sap of the lacquer tree, extends the longevity of lumber. The Hanja fonts look laser sharp even after more than 700 years.

One of the mysteries surrounding the Palman Daejanggyeong printing blocks is the machine-like consistency of the handcarved Hanja characters. All 52 million characters are uniformly consistent, as if inscribed by a single person with impeccable calligraphy.

Famed Joseon calligrapher Chusa Kim Jeong-hui (1786 -1856) said, “The calligraphy in Palman Daejanggyeong is done by sinpil (divine writing), not by yukpil (person’s writing).”

|

Buddhist temple Haeinsa’s Janggyeong Panjeon, where the more than 81,352 printing blocks are archived, is a scientific masterpiece from the Joseon era. Photo © 2021 Hyungwon Kang |

Haeinsa’s Janggyeong Panjeon, the buildings where the more than 81,000 printing blocks are held, is a scientific masterpiece from the Joseon era in the 15th century.

The floor and foundations of the depository buildings were reinforced with charcoal, salt and plaster to regulate moisture and humidity while also repelling bugs.

The unique two-row open design of the Janggyeong Panjeon explains how the wooden printing blocks have withstood centuries of changing weather and harsh elements, without modern temperature and moisture controls or heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems.

The south-facing walls have larger openings on the bottom row while north-facing walls have larger openings along the top row, facilitating constant 24/7 air circulation. Further, the high altitude location of the structures on the Gayasan mountain ridge means continued air flow.

Between the outside weather and the unique wall design, the depository has its own ecosystem.

After more than 700 years, the wooden printing blocks remain perfectly maintained in their original state with no warping or bug infestation of the wooden pieces.

Both the wooden printing blocks and the archives building have been separately listed by UNESCO’s Memory of the World Program.

By Hyungwon Kang (hyungwonkang@gmail.com)

Korean American photojournalist and columnist Hyungwon Kang is currently documenting Korean history and culture in images and words for future generations. -- Ed.By Korea Herald (

khnews@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)