BEIJING (AFP) ― Mo Yan has focused an unflinching eye on what he calls the darkness and ugliness of 20th-century Chinese society in a prolific writing career that on Thursday landed him the 2012 Nobel prize for literature.

Mo Yan, one of China’s leading writers of the past half-century, became the first Chinese national and just the second Chinese-language writer to be awarded the coveted prize.

The 57-year-old, whose real name is Guan Moye, is perhaps best-known abroad for his 1987 novella “Red Sorghum”, a tale of the brutal violence that plagued the eastern China countryside ― where he grew up ― during the 1920s and 30s.

The story was later made into an acclaimed film by leading Chinese director Zhang Yimou.

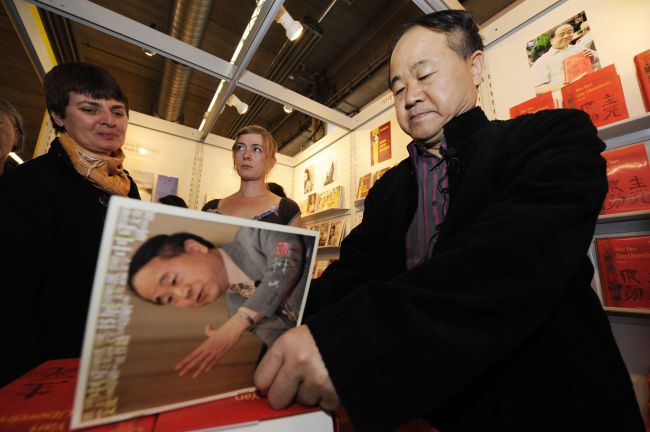

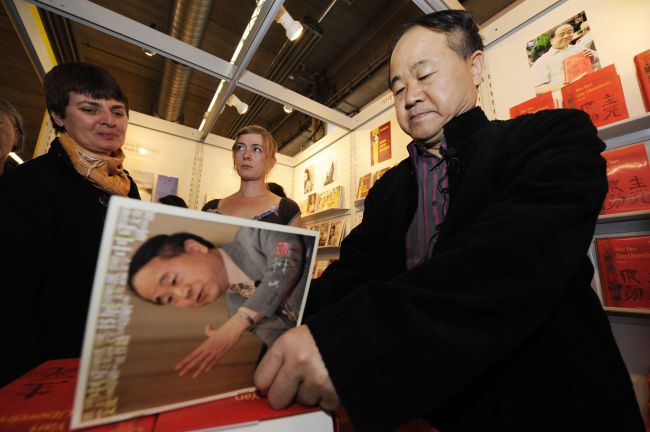

|

This Oct. 15, 2009, photo shows Chinese author Mo Yan taking part in a reading at the 61st Frankfurt Book Fair in Frankfurt. (AFP-Yonhap News) |

In a style that has been compared to the magical realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Mo Yan authored other acclaimed works including “Big Breasts and Wide Hips”, “Republic of Wine” and “Life and Death are Wearing Me Out”.

He has also written dozens of other novels, novellas, and short stories, generally eschewing contemporary issues and instead looking back at China’s tumultuous 20th century in tales often infused with politics and a dark, cynical sense of humour.

The backdrops for his various works have included the 1911 revolution that toppled China’s last imperial dynasty, Japan’s brutal wartime invasion, newly Communist China’s failed land-reform policies of the 1950s and the madness of Mao Zedong’s 1966-76 Cultural Revolution.

Touching on such eras means flirting with crossing the thin line that divides what is acceptable and what is politically taboo for the Communist Party.

His latest novel, 2009’s “Frog”, is considered his most daring yet, due to its searing depiction of China’s “one child” population control policy and the local officials who ruthlessly implement it with forced abortions and sterilisations.

The heroine of the novel is a midwife who is an enthusiastic advocate of such practices.

But she later breaks down in remorse after a drunken hallucination in which she is attacked by thousands of frogs whose croaks are the wails of the babies she has aborted.

Despite such content, Mo Yan has so far deftly managed to avoid running into serious trouble with Communist authorities.

This has been aided by his position as vice chairman of the state-sanctioned Chinese Writers Association.

The newly crowned Nobel laureate also has supported official policies on art and culture. These state that art and literature must serve the socialist cause ― and, by extension, not threaten Communist Party rule.

Some of his contemporaries have criticised him over this. But in a speech at the 2009 Frankfurt Book Fair, Mo Yan insisted that a writer be judged solely on his works.

“A writer should express criticism and indignation at the dark side of society and the ugliness of human nature,” Chinese media have quoted him saying.

“Some may want to shout on the street, but we should tolerate those who hide in their rooms and use literature to voice their opinions.”

Chinese literary expert Eric Abrahamsen called Mo Yan “a great writer” who tells “the ‘big’ stories of China, who’s writing the Great Chinese Novel.”

“So many of modern China’s stories are political in nature, simply because politics has shaped so much of recent Chinese history and society,” said Abrahamsen, who runs the China Publishing Industry Newsletter.

“That inevitably means he’s going to write about politics. He’s also very canny about what can and can’t be written.”

Mo Yan was born in the rural eastern province of Shandong and has set many of his works in his home county of Gaomi.

He began writing while serving in the People’s Liberation Army in the early 1980s ― choosing the pen name Mo Yan which means “Don’t speak.”

The author has said it refers to being told to pipe down as a chatty child, but also to letting one’s writing do the talking for them.

Despite the occasional banning of an individual book, Mo Yan’s most important works have largely remained in print.

He has won numerous literary awards, including the 2009 Newman Prize for Chinese Literature and the 2007 Man Asian Literary Prize, and many of his works have been translated into English and other languages.

Due to the official favour Mo Yan enjoys, his Nobel win will likely be touted by China as a victory for the state literature policy of the Communist Party, which muzzles critical voices among writers.

That would contrast with Beijing’s reaction toward previous China-related Nobel wins.

The government was highly critical of the literature prize awarded to author Gao Xingjian in 2000, the first Chinese-language writer to win the award. Gao had fled China in the 1980s and took French citizenship in 1997.

Beijing also loudly denounced the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama in 1989 and to jailed political dissident Liu Xiaobo in 2010.