Last week’s hike in U.S. interest rates, the first in nearly a decade, has ended an era of ultraeasy money in the world’s largest economy that is now deemed to have gone beyond the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

Emerging market countries, many of which have been considered particularly vulnerable to the impact of a U.S. rate rise, seemed barely rattled by the widely expected move.

The initial response, however, cannot be allowed to ease concerns about the threat to be posed by a tightening U.S. monetary policy to emerging economies, say analysts and economic commentators at home and abroad. As its own forecast suggests, the U.S. Federal Reserve is set to keep a streak of rate rises in the coming year to a range of 1.25-1.5 percent.

Though gradual as promised by Fed policymakers, a continuous rise in U.S. interest rates will likely place developing countries in an increasing danger of a credit crunch, with international financial experts forecasting that emerging markets will suffer their first net capital outflow this year since the late 1980s.

This receding tide of money is set to be combined with a continuous fall in commodity prices amid a prolonged global economic downturn to amplify the predicament of many emerging countries in the year to come.

Economists agree it is unlikely that developing economies will suffer a crisis of the same magnitude as the one that hit them in 1997-98 as they have built up foreign reserve firewalls. But some fragile economies could still be pushed to the brink.

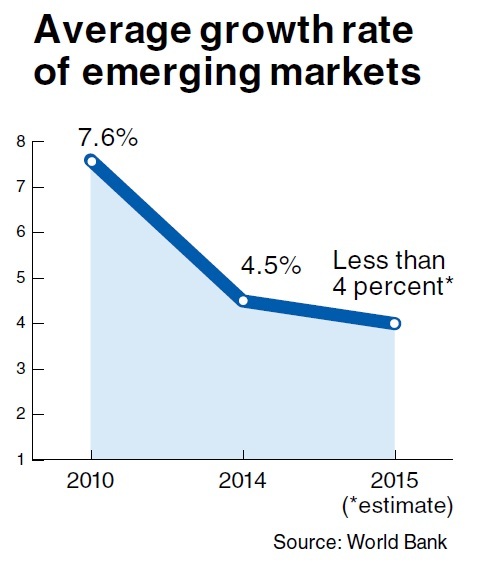

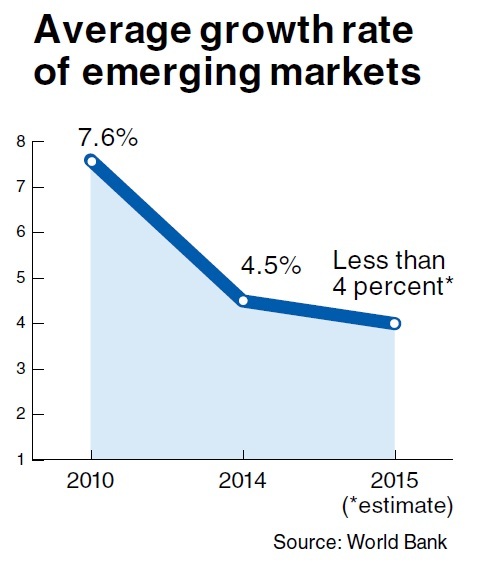

Recent figures from the World Bank suggested emerging countries might be entering an era of chronic low growth.

The average rate of growth in 24 emerging economies, including BRICS ―Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa ― decreased from 7.6 percent in 2010 to 4.5 percent in 2014. It is estimated to go below 4 percent this year. Accordingly, the gap between annual growth rates of developed and developing economies has narrowed to around 2 percent from an average 4.8 percent in 2003-2008.

Rich countries are expected to show solid growth next year, with the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan set to keep quantitative easing to boost their economies.

This positive outlook for the developed world, however, could be clouded by the deepening slump in emerging markets, which together account for 35 percent and 32 percent of global gross domestic product and trade, respectively.

The greatest challenge may be presented by a continuous slowdown in China, the world’s No. 2 economy. Besieged by rising capital outflows, Beijing could be pushed to let its currency, the renminbi, depreciate against the U.S. dollar next year, a move that is likely to spark a currency war in Asia and beyond.

Korea may well be concerned that a deepening slump in emerging markets will pose serious threats to its economy that has been struggling with sagging exports.

Officials at the Korea-Trade Investment Agency say an increasing number of buyers from emerging countries have canceled orders for Korean products.

Korean manufacturing exporters may have more difficulties keeping their competitiveness in global markets, with China, Japan and the European Union continuing to let the value of their currencies remain low.

“It is inevitable that local companies will see their price competitiveness weaken against their Chinese, Japanese and European rivals,” said Jang Soo-young, a KOTRA official in charge of trade strategy. “They should step up efforts to produce more qualitative products and find new markets.”

Hyundai Research Institute noted in a recent report that a reduction in Korea’s exports to emerging markets would more than offset an increase in the shipment of its goods to the U.S. that is seen to be on a path of robust growth.

In a meeting with her economic aides earlier this month, President Park Geun-hye cited potential volatility in emerging countries when she called for an economic contingency plan. Her remarks apparently reflected her concern that the Korean economy may be drawn into a crisis if the fallout from volatile emerging markets is coupled with a delay or failure in structural reforms to strengthen its fundamentals.

In this regard, she was seen to strike a right note in a Cabinet meeting this week when she described a global rating agency’s recent upgrading of Korea’s sovereign credit rating as a “message of warning” that it could be downgraded again if the country failed to carry out structural reforms.

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Health and care] Getting cancer young: Why cancer isn’t just an older person’s battle](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050043_0.jpg)