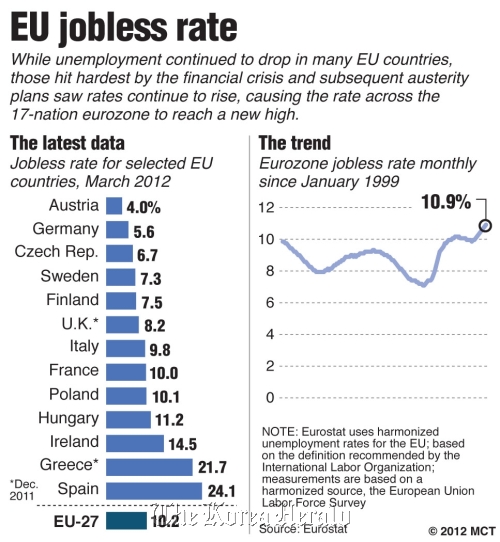

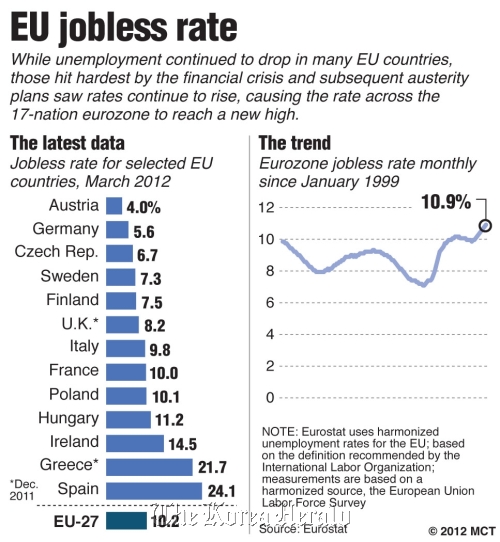

Jobless hits record high of 10.9 percent as recession, austerity bite

LONDON (AP) ― The 17 countries that use the euro are facing the highest unemployment rates in the history of the currency as recession once again spreads across Europe, pressuring leaders to focus less on austerity and more on stimulating growth.

Unemployment in the eurozone rose by 169,000 in March, official figures showed Wednesday, taking the rate up to 10.9 percent ― its highest level since the euro was launched in 1999. The seasonally adjusted rate was up from 10.8 percent in February and 9.9 percent a year ago and contrasts sharply with the picture in the U.S., where unemployment has fallen from 9.1 percent in August to 8.2 percent in March. Spain had the highest rate in the eurozone, 24.1 percent ― and an alarming 51.1 percent for people under 25.

Austerity has been the main prescription across Europe for dealing with a debt crisis that’s afflicted the continent for nearly three years and has raised the specter of the breakup of the single currency. Three countries ― Greece, Ireland and Portugal ― have already required bailouts because of unsustainable levels of debt.

Eight eurozone countries, including Greece, Spain and the Netherlands, have seen their economies shrink for two straight quarters or more, the common definition of a recession.

Economies are contracting across the eurozone as governments cut spending and raise taxes to reduce deficits. That has prompted economists to urge European Union policymakers to dial back on short-term budget-cutting and focus on stimulating long-term growth.

“The question is how long EU leaders will continue to pursue a deeply flawed strategy in the face of mounting evidence that this is leading us to social, economic and political disaster,” said Sony Kapoor, managing director of Re-Define, an economic think-tank and policy advisory company.

In a nod to shifting attitudes about austerity, European Central Bank president Mario Draghi recently called for a “growth pact” in Europe to work alongside the “fiscal pact” that has placed so much importance on controlling government spending.

Bailout fears have intensified in recent months as Spain, Italy and other governments face rising borrowing costs on bond markets, a sign that investors are nervous about the size of their debts relative to their economic output. Austerity is intended to address this nervousness by reducing a government’s borrowing needs, but there has been a negative side effect: As economic output shrinks, the debt burden actually looks worse.

Economists recommend pro-growth measures including reducing red tape for small businesses, making it easier for workers to find jobs across the eurozone and breaking down barriers that countries have created to protect their own industries. Some economists go a step further and say governments should actually increase spending while economies are so weak ― and make reining in deficits a longer-term goal.

The central bank has tried to reinvigorate Europe’s financial system by lowering interest rates and extending $1.3 trillion in cheap, three-year loans to banks. Banks have used some of the money to purchase government bonds, which briefly eased pressure on countries’ borrowing costs. But interest rates on Spanish and Italian bonds have crept even higher in recent weeks.

Across Europe, austerity has come in the form of layoffs and pay cuts for state workers, scaled-back expenditures on welfare and social programs, and higher taxes and fees to boost government revenue.

With elections in Greece and France this weekend, there are hopes ― certainly among the 17.4 million people unemployed in the eurozone ― that Europe may temper, if not reverse, its focus on austerity.

“With the potential changing of political leaders, coupled with confirmation that nearly half of the eurozone is officially in recession, the strategy of continuing austerity is being widely challenged,” said Gary Jenkins, managing director of Swordfish Research.

France’s Socialist presidential candidate, Francois Hollande ― who is leading incumbent Nicolas Sarkozy in the polls ― has said he would re-negotiate the eurozone’s austerity-focused fiscal pact to include measures that would encourage growth. The pact requires countries to keep their budget deficits within 3 percent of economic output ― a major reason why Spain, Italy and other governments are slashing spending.

Austerity has been pushed hardest by Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, as a way to convince markets and international investors that the region has a grip on its problems. However, Germany’s economy is beginning to show signs of vulnerability, which analysts say could pressure Chancellor Angela Merkel to moderate her stance.

April unemployment figures from Germany’s statistics office showed a monthly rise of 19,000, only the second increase in the past 25 months.

A survey of Europe’s manufacturing sector released Wednesday suggests further pain is on the horizon.

The eurozone’s monthly purchasing managers index ― which tracks sales, employment, stock levels and prices ― fell to 45.9 in April from 47.7 the previous month, according to financial information company Markit. Anything below 50 indicates a contraction in activity. Germany’s index slumped to 46.2, its lowest level since the summer of 2009.

As Spain’s conservative government pushes ahead with more austerity, its recession is expected to deepen, raising doubts that it will be able to meet its deficit-reduction targets.

Greece has the second highest unemployment rate, though its figures date back to January. The country, which has received two massive international bailouts to avoid a messy default on its debt payments, has a jobless rate of 21.7 percent, with 51.2 percent of young people out of work.

Austria had the lowest unemployment rate in the eurozone, at 4 percent. The Netherlands, which saw its government collapse last week over disagreements on austerity measures, was not far behind at 5 percent.

The unemployment rate across the wider 27-country European Union, which includes non-euro members like Britain and Poland, was 10.2 percent, unchanged from February but still higher than the 9.4 percent recorded a year before.