The last scene of Oscar Hijuelos’ new memoir, “Thoughts Without Cigarettes” (Gotham Books, $27.50), is a moment of contact with a ghost -- that of his father, Pascual.

“I remember when that moment came to me,” says Hijuelos. “It was a mystical reaching of a different dimension. I don’t know what happens when you die, but there is a mystical presence in our lives that extends to people who are no longer around, and you can connect with them in your emotions. At the moment, I didn’t understand it, but now I know: Damn, he was there.”

Hijuelos had just learned he’d won the 1990 Pulitzer Prize for fiction for his second novel, “The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love.” It was the first fiction Pulitzer ever to go to a Latino writer.

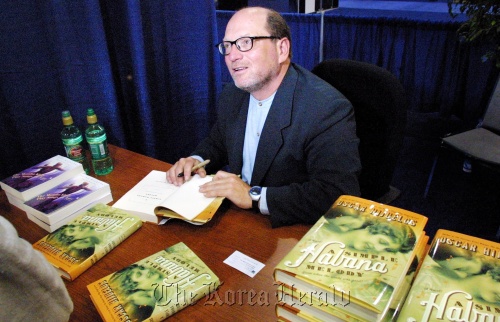

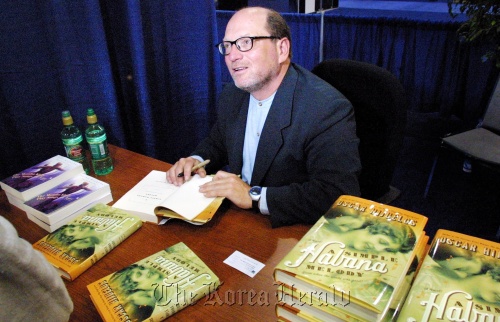

|

Pulitzer Prize winning novelist Oscar Hijuelos signs books at the American Association of Museums conference at the Dallas Convention Center on May 15, 2002. (MCT) |

“When I won the prize,” says Hijuelos, speaking by phone from Manhattan, “all I could think of was the mystical feeling, ‘You’ve done your folks right.’”

Yolanda Padilla, assistant professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania, calls his Pulitzer “a great point of pride for many Cuban Americans and Latinos generally. And it opened up publishing opportunities for Latino writers because presses on the East Coast saw that there was a demand for stories about Latina/o culture.”

Indeed, Hijuelos is thought of as a Cuban-American writer -- “but the irony of my work, and my life,” he says, “is that I was cut off from my Cubanness pretty early, and in some ways, I’ve had to write my way back to it.”

That makes a fine summary of “Thoughts,” which falls into two parts. In the first, young Oscar is born in Manhattan, to two Cubans recently come to the States. He‘s a fair-haired kid known as el rubio (“the blond”) to the Cubans around them. He visits Cuba with his mother in 1955 and returns -- only to fall ill of a kidney disease, possibly picked up in Cuba. He’s forced to spend most of a year in the hospital. That year, surrounded by no Spanish speakers, effectively cuts him off from Cuban culture.

“I was cut off in so many ways from my legacy,” he says. “First, by my appearance, because I didn‘t ’look Cuban.‘ Then by my disease. And later, the communist revolution cut me off from my relatives.” Once well, the young Oscar resists his mother’s attempts to reintroduce him to Spanish.

That leads directly to the second part of “Thoughts,” in which Hijuelos discovers writing, and via writing, himself. “I was trying to replace what I always should have had,” he says. “It‘s a uniquely American story: trying to figure out what you are.” Hijuelos, 60, had an exciting time -- the early 1970s -- in which to learn how to write, and a stellar series of mentors. Among his teachers at City College of the City University of New York were Donald Barthelme and Susan Sontag, two of the era’s most prominent writers and critics.

“I was the roughest, most terrible writer in the world,” Hijuelos says. “But Barthelme was always very kind to me, and as time passed, the quality of my writing changed, and he began to take my work much more seriously.” Sontag, too, “although a totally brilliant person, related to me very nonintellectually, as a regular person. I had a deep element of Catholic spiritualism she really loved and encouraged me to explore.”

Hijuelos began to write of his Cuban roots, amassing material that would later surface in his first novel, 1983’s “Our House in the Last World.” In “Thoughts,” Hijuelos reports that “in that process of digging up the dead (resurrecting them, as it were), I began to experience very bad nights of restless sleep and disorienting dreams,” so bad that he sought therapy.

But “House” was well received. “When it came out, for the first time in a long time, I felt a sense of wholeness, about myself, I mean,” Hijuelos says. Then came the thunderclap of success that greeted “Mambo Kings”: a Pulitzer, a movie, a moment with his father’s ghost.

“Hijuelos is one of the most famous U.S. Latino writers,” Padilla says. “He‘s up there with Sandra Cisneros, Julia Alvarez and Junot Diaz. Despite this, I think his work is underrated. He’s not given enough credit for the complex characters he creates or the way he uses the subtleties of everyday life to give us powerful insights into those characters.” She praises his “vibrant representation of Cuban American mambo culture in New York in the 1940s and ‘50s” in “Mambo Kings.”

“But I think that aspect gets focused on in part because it’s the most ‘exotic’ element of the book,” she says. “It’s the sort of element that the larger culture often wants to see in a ’Latino‘ novel.” She wishes he’d get more attention for his focus “on the workplace and on labor, in order to craft intricate character studies that are very powerful.”

Hijuelos grumbles about a U.S. literary establishment “that still typecasts Latino writers, still leaves us out of the discussion. I mean, I love Jonathan Franzen and Michael Chabon, too -- but our books are as American as theirs.” He still has a hesitant affair with the Spanish language, “but if the vibe is right, I can settle into it.”

And he confesses a lingering sadness about what he lost and had to struggle to recover. “Every year you’re away from the fount of what you are, I feel sad about it. I kick myself: ’Why didn‘t I move to Havana for three years? Why am I a Cuban-American writer who’s lived in Italy longer than he’s been in Cuba?’”

Yet that’s the thing he likes about “Thoughts Without Cigarettes”: “It tells the story of my doubleness. As for Cuban culture, it turns me on, and I feel protective of it, because it is so often treated superficially. I hope I have contributed to it in some way.”

By John Timpane

(The Philadelphia Inquirer)

(McClatchy-Tribune Information Services)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)