I’ve outgrown J.D. Salinger, and I don’t know where that leaves me.

I was 10 when my father handed me “The Catcher in the Rye,” and I found not just a voice for all the wild despair and sudden inexplicable elation of adolescence but an acknowledgement that these feelings did not occur in a vacuum. Salinger reached into the “vale of tears” catechism of my Irish Catholic upbringing and lifted me out by my hair ― don’t listen, he said, they’re all phonies, just keep your eyes open for small moments of beauty, and you will find them between the lies and the obscenities.

I felt like my life had been saved and in tribute spent the next few years of my life calling people “Ackley kid” and prefacing far too many of my comments with “if you want to know the truth.”

By college I had become a Salinger snob, the kind who all but shrugs off “Catcher” (“yes, it’s the most popular, but is it his best?”) to sing the praises of “Nine Stories” (all of them, not just the ones about Esme and Bananafish), “Franny and Zooey” and “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters.” (“Seymour: An Introduction” was beyond me.)

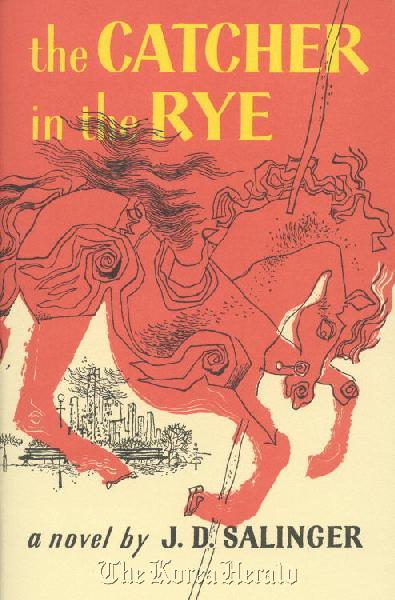

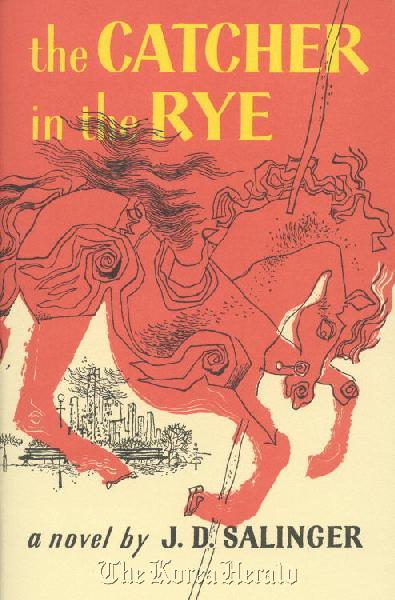

|

“Catcher in the Rye” by J.D. Salinger |

If Holden Caulfield was the headliner, the Glass family chronicles were the holy text, their teetering balance of intellectual and spiritual, of the mighty and the mundane a heady brew for anyone trying to live a life of high drama and actual worth. His characters painted their nails, pushed off their shoes, sat in the tub, lighted a cigarette, petted the cat, drank a glass of milk, lighted another cigarette, but to a man, woman and child, they sought and passionately believed in a state of understanding greater than their own. Call it God, grace or spiritual enlightenment, every character lived and breathed at the glowing edge of something larger. For all his arched-brow cynicism, Salinger was just as sentimental and religious as C.S. Lewis.

He was also a deliciously specific and evocative writer. To this day I can close my eyes and see Phoebe’s blue coat, the tangerine Les offered Franny, the damp and frayed letter Zooey reads in his cooling bath, the arch of the girl’s foot Seymour kisses before heading up to the hotel room to shoot himself.

But it was the talk that sold him the hardest to those of us who still believed in the power of wit, who longed for a time when conversation was an art form, when talking was a talent. Salinger wasn’t stingy with the dialogue, or monologue. It went on for paragraphs. In “Franny and Zooey” it went on for pages. In fact, you could argue, and some have, that Salinger is all talk.

And that is what I outgrew.

For years I read and reread these books, anticipating scenes or sentences, delighted by their familiarity and unfailing ability to make me smile and cry and think. My devotion lasted three decades, survived the obsessive privacy of the writer and the lacerating slivers of biography that emerged through others ― Joyce Maynard’s icky memoir of living with Salinger when she was a barely legal teenager, the various lawsuits, even friends’ tales of chance Salinger sightings. I didn’t care much if the man was “a bastard,” to use one of his favorite pejoratives, or just a dairy-fearing neurotic, and as I aged I cared even less. If we judged art by the sanity or kindness of the artist, our museum walls would be bare, our libraries empty.

Then last year, I picked up “Franny and Zooey” again and almost immediately put it down. So much talk, so little real understanding. So much self-indulgence, so little enlightenment. Suddenly I understood why Seymour had committed suicide. It wasn’t because of the war or his new wife or that he didn’t fit into an American definition of “normal.” It’s because he never had an original thought. Anyone who spends his youth copying quotations from “the great minds” onto shirt boards and his bedroom wall isn’t seeking illumination; he’s killing time.

Even the many characters in the short stories seemed sad and limited, so very, and, yes, I will say it, young. Perpetually, categorically and inexorably young. Even the few who weren’t children. Almost all of Salinger’s characters view the world in a perpetual state of judgmental longing, with sympathy or empathy only for a select few, mainly themselves. Salinger worshiped children, believed that young people saw the world more clearly than adults whose heads were cluttered with martinis and prejudice. In “Teddy,” the young visionary is so clear-sighted he propels himself to his own rather horrible death because that is how he has seen it is supposed to happen.

In that way, Salinger is as old-fashioned as Bronson Alcott and others who believed that children were more divine than adults because they had so lately been in the literal presence of the angels. Perhaps.

By Mary McNamara

(Los Angeles Times)

(McClatchy-Tribune Information Services)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)