Thomas is a 58-year-old manager at a pharmaceutical company. One spring morning after jogging, he noticed a slight fluttering in his chest. He decided to ignore it.

But next morning he noticed he could not move his left arm and leg. Upon careful questioning, Thomas revealed that he had had several episodes of fluttering for the last few months. Thomas was diagnosed with a stroke and a type of arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation.

Cardiac arrhythmia is a term for any condition in which there is abnormal heart rhythm. The heartbeat may be too fast (more than 100 beats per minute) or too slow (less than 60 beats per minute), and may be regular or irregular. Some arrhythmias are life-threatening medical emergencies that can result in cardiac arrest and sudden death.

Others cause symptoms such as palpitation, an abnormal awareness of heart beat. Others may not be associated with any symptoms at all, but may predispose the patient to a potentially life-threatening stroke or embolism.

Atrial fibrillation is the most commonly sustained cardiac arrhythmia, occurring in 1-2 percent of the general population and involving the two upper chambers (atria) of the heart. Its name comes from the fibrillating (i.e., quivering) of the heart muscles of the atria, instead of a coordinated contraction. It can often be identified by taking an irregular heart beat or an electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). Risk increases with age, with 5-15 percent of people aged 80 or older having AF. The lifetime risk of developing AF is around 25 percent in those who have reached age 40.

AF is often asymptomatic but it may result in palpitations, fainting, chest pain or congestive heart failure.

The patients who have first detected AF may or may not have had previous undetected episodes. In most cases of paroxysmal AF the episodes will self-terminate in less than 24 hours. If the episode lasts for more than seven days, it is called persistent AF. If cardioversion to normal heart rhythm is unsuccessful, the patient’s AF is referred to as permanent.

AF is linked to several cardiac causes, but may occur in otherwise normal hearts. Known associations include hypertension (high blood pressure), coronary artery disease, mitral stenosis, excessive alcohol consumption (“binge drinking” or “holiday heart syndrome”) and hyperthyroidism.

People with AF usually have a significantly increased risk, by as much as five-fold, of stroke.

Stroke risk increases during AF because blood may pool and form clots in the poorly contracting atria and especially in the left atrial appendage. The risk of stroke depends on the number of additional risk factors.

Many people with AF have stroke risk factors and AF is a leading cause of the condition; one in five of all strokes is attributed to it. The risk factors of stroke include previous strokes, congestive heart failure, an age of more than 65 years old, hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

The main goals of treatment for AF are to reduce symptoms and prevent severe complications associated with AF. Prevention of AF-related complications relies on antithrombotic therapy, control of ventricular rate and adequate therapy of concomitant cardiac diseases. Rate or rhythm control is used to achieve stable circulation, while anticoagulation is used to prevent stroke.

AF may be treated with medications which either slow the heart rate or return the heart rhythm back to normal. Synchronized electrical cardioversion may also be used to convert AF to a normal heart rhythm.

Surgical and catheter-based ablation therapies may also be used to prevent recurrence of AF in certain individuals. People with AF are often given anticoagulants such as warfarin to protect them from stroke.

I advise you to get regular ECG checkups at the age of more than 40 years old to prevent severe complications associated with AF and stroke.

|

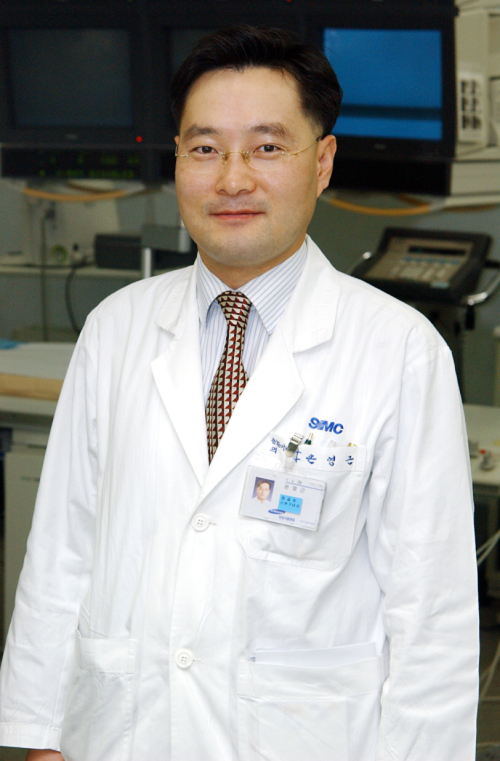

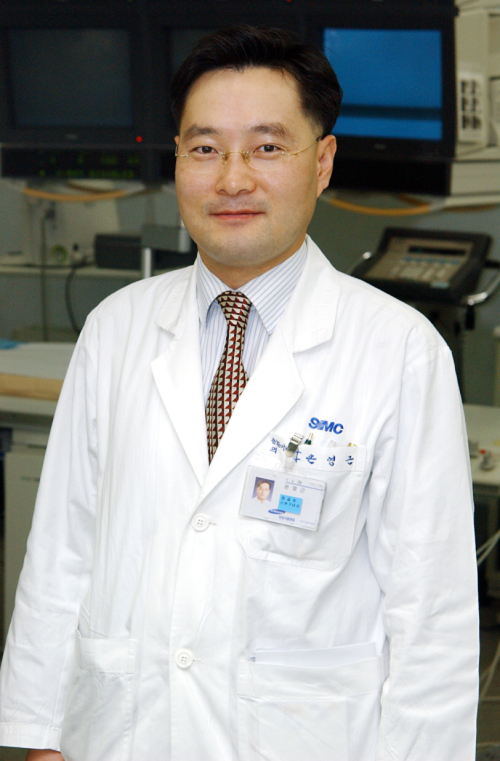

On Young-keun |

By On Young-keun MD, Ph.D., FHRS

The author is an associate professor of cardiology at the department of internal medicine at Samsung Medical Center ― Ed.

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)