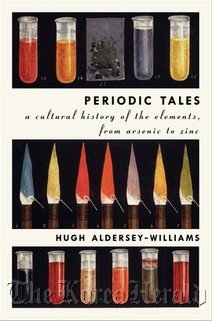

A charming look at the elements

Periodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, From Arsenic to Zinc

By Hugh Aldersey-Williams

(Ecco, $25)

Some people collect coins or baseball cards. Others collect stamps or Pez dispensers. Hugh Aldersey-Williams collects the building blocks of the universe.

Aldersey-Williams has been trying to collect pure samples of every element known to humankind -- from the common to the rare, the inert to the lethal. His quest sprang from a simple desire: to see and feel the elements that otherwise seem to exist only as abbreviations on the periodic table.

The author’s scientific sentimentality may be unusual. But he makes it easy to share his passion with his latest book, the charming “Periodic Tales: A Cultural History of the Elements, From Arsenic to Zinc.”

Few people give elements a second thought outside of chemistry class, but each one has an interesting story. The quest for gold drove some cultures to explore the world, while other cultures dismissed it as useless. Platinum is as plentiful as gold but it’s more valuable because of artificially created demand. And chlorine changed the way nations waged war.

In this context, the elements are surprisingly fascinating. Aldersey-Williams writes about how each element was discovered, explains its place in human history and describes the cultural changes it wrought.

The vignettes are interesting and eloquently written. The only drawback is quantity -- with more than 100 elements, it’s hard to keep some of the stories straight.

Aldersey-Williams eases the journey by avoiding complex language. Readers won’t need a strong science background to appreciate the stories.

A number of interesting patterns emerge throughout the book.

For example, discoveries of new elements typically captured the public’s imagination at first. People were easily convinced that the new element had therapeutic benefit, and entrepreneurs would try to capitalize by adding the element -- or at least its name -- to their products.

Over time, as scientists found side effects associated with the elements, the substances would be phased out and the excitement would subside.

The best part of the book is the author’s evident passion. For example, after reading about an alchemist who extracted faintly glowing phosphorus from human urine, Aldersey-Williams tries to duplicate the feat. It’s not often that story about urine is so gripping.

“Periodic Tales” is a relatively quick read, and Aldersey-Williams writes with simplicity and elegance. The stories may not help you on your next chemistry test, but they’ll help you appreciate the building blocks that are all around us yet all too easy to overlook. (AP)

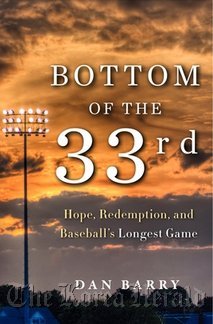

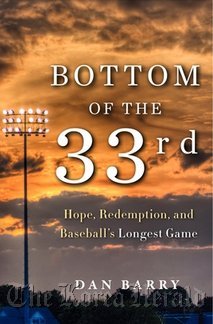

Pro baseball’s longest game

Bottom of the 33rd: Hope, Redemption, and Baseball’s Longest Game

By Dan Barry

(Harper, $29.99)

As any disciple of baseball knows, the sport is much more than a game, much more than nine men tossing a ball on an emerald diamond. It is a connection to the divine, a celebration of hometown heroes, a ballad of loss and longing and love. Life encapsulated.

For the faithful, baseball is a receptacle of memories, dreams, history. And a trip to a ball game is a visit to the cathedral, a ritual brimming with sounds and sights and stories.

So, it follows that the longest game ever recorded in professional baseball would be rife with untold tales of triumph and tragedy, sorrow and struggle, comedy and competition. Untold, that is, until now.

In “Bottom of the 33rd: Hope, Redemption, and Baseball’s Longest Game,” Dan Barry, the gifted New York Times national columnist, has crafted a meticulously reported, finely embroidered account of the infamous minor league face-off between the Pawtucket Red Sox and the Rochester Red Wings.

The game, which began on the cold Saturday evening of April 18, 1981, in the flailing textile town of Pawtucket, Rhode Island, would straggle into the frigid dawn of Easter Sunday before being stopped in the 32nd inning. Two months and one inning later, on June 23, Pawtucket first baseman Dave Koza drove in the winning run to end the marathon match.

But Barry does more than simply recount the inning-by-inning-by-inning box score. He delves beneath the surface, like an archaeologist piecing together the shards and fragments of a forgotten society, to reconstruct a time and a night that have become part of baseball lore.

Every waft of the ball, every thwack of leather against ash, every inning swallowed by the night is somehow linked to every pitch, and swing, and long fly ball that came before, in every ball park in every small town and big city across America.

“How short, now, the longest game seems. How ephemeral. On a night and early morning set aside for prayer, reflection, and everlasting joy, a baseball game insisted on the suspension of ordinary time,” Barry writes. “It forced those watching the game to contemplate cosmic issues that transcend the successive crises of balls and strikes.”

In prose that echoes of Walt Whitman, Barry sings the carols of the jittery batboy in the dugout, the baseball wife tethered to her husband’s dreams of glory, the pitchers milling in the bullpen, the fans lashed by frigid winds in the bleachers, and the future hall-of-famers, never-heard-ofs and whatever-happened-tos on the playing field.

It is a teeming cast of characters as colorful and changeable as a kaleidoscope.

The clubhouse manager named Hood, a fixture in the stadium, who once wheeled the team’s dirty uniforms through the streets in shopping carts. The team owner, a poor kid from Woonsocket who hustled his way to riches and raised McCoy Stadium from the depths of disrepair. A father and son who ride out eight cold and dark hours in the stands, holding fast to a pledge never to leave a game “until the last out is recorded.”

Then, there are the players. Some who went on to become baseball royalty: Wade Boggs, Cal Ripken Jr., Bobby Ojeda. Some who faded into obscurity: Drungo Hazewood, Danny Parks and Koza, who never made it to the majors.

Barry’s storytelling, like America’s national pastime itself, ambles along in a slow, steady cadence that builds and unravels with no thought of a clock. In other words, it is designed to be savored, not sped through.

But, in the end, like that game played on a long-ago Easter Sunday weekend, the time spent on the Pawtucket field will be worth it.

Because, as Barry says, “we are bound by duty. Because we aspire to greater things. Because we are loyal. Because, in our own secular way, we are celebrating communion, and resurrection, and possibility.” (AP)

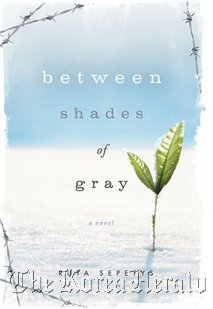

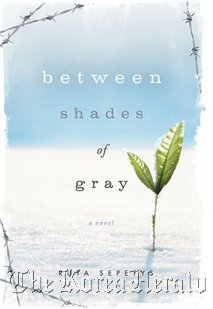

Dark time in Lithuania

Between Shades of Gray

By Ruta Sepetys

(Philomel, $30)

In 1941, the lives of 15-year-old Lina Vilkas, her brother and their mother are turned upside-down when they are forced from their home in the middle of the night. Deemed “enemies of the people,” they are expelled from Lithuania and forced to work in a Soviet labor camp in Siberia, where prisoners are routinely starved, brutalized and killed.

Under the 1939 German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact, areas of Eastern Europe were divided between the two countries. The Baltic States of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia were annexed by Stalin, who deported members of the intelligentsia and their families to maintain control of the region.

These countries were under Soviet control for over 50 years until declaring their independence in the early 1990s. Unlike the well-documented atrocities of Jewish people in Nazi Germany, accounts of Soviet brutality have only recently become known.

“Between Shades of Gray” is a fictional story inspired by actual accounts and experiences of prisoners. It is told from the viewpoint of Lina, an aspiring artist, and follows the Vilkas family during their first few years of imprisonment in Siberia.

Lina is feisty and opinionated, a dangerous combination in an era of communist oppression. She secretly documents Soviet atrocities in her drawings.

Fellow prisoners become an extended family of sorts while working at a collective farm harvesting potatoes and beets.

Author Ruta Sepetys includes many agonizing scenes of cruelty: Soldiers round up a woman and her newborn child for deportation minutes after the woman has given birth. A callous commander buries prisoners as a joke, making them believe they are slated for execution. And there are grim executions of grieving mothers whose emotional outbursts are not tolerated.

Although the depravity is disheartening at times, Sepetys imbues uplifting stories of compassion, humor and a blossoming romance between Lina and a fellow prisoner.

“Between Shades of Gray” is an engrossing and poignant story of the fortitude of the human spirit in a dark time in Lithuanian history. (AP)

![[Today’s K-pop] Blackpink’s Jennie, Lisa invited to Coachella as solo acts](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/21/20241121050099_0.jpg)