Shannon Heit, 33, trembled with rage as she recalled the moment two months ago when she heard that a Korean boy had been killed by his adoptive father in the U.S.

Heit, a freelance translator in Seoul, is not related to the boy. But she said that, as a Korean-American adoptee herself, she felt a deep connection to him, and a greater pain.

Hyunsu O’Callaghan, 3, died on Feb. 3 at a children’s hospital in Maryland, just four months after he was adopted by an American couple.

Brian O’Callaghan, the boy’s father, claimed that the boy slipped while taking a shower, but an autopsy revealed a fractured skull, bruises to the forehead, swelling of the brain and multiple contusions consistent with impact trauma. Authorities in the U.S. said the evidence showed that the boy had been “basically beaten from head to toe” by his adoptive father.

O’Callaghan was arrested and indicted last month with first-degree murder and child abuse for the death of his own son.

“To me it’s just like really sad and heartbreaking … even just thinking about the last minutes that he would have spent not even being able to express himself,” she said, adding that the boy, who was disabled, may not have been able to communicate with any of his family in the U.S.

|

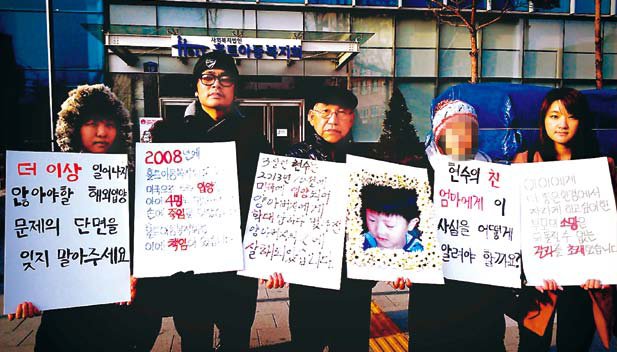

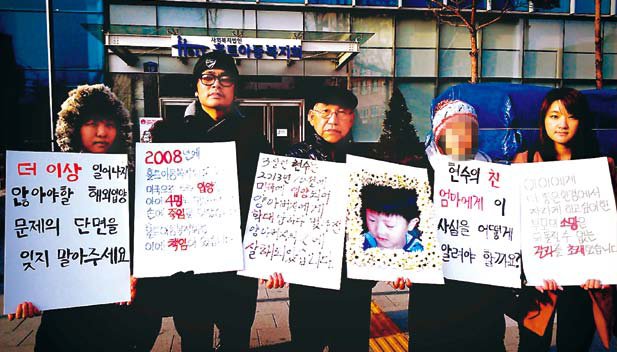

Shannon Heit (right), a Korean-American adoptee, holds rally with other adoptees in front of an adoption agency in Seoul which arranged the adoption of a 3-year-old boy beaten to death by his adoptive father in February in the U.S |

Out of despair, she took to the streets to tell people about how Hyunsu died and the organizations she thought should be held responsible.

Heit has been standing outside offices of those organizations, from the National Assembly to the adoption agency that arranged Hyunsu’s inter-country adoption, holding a picture of the boy and sign saying, “Sorry we couldn’t protect you.”

“Hyunsu is not the only one. There are more to protect,” she said.

Heit is one of several Korean adoptees raising concerns about Korea’s inter-country adoption system, which they say fails to protect young adoptees’ basic human rights.

Jane Jeong Trenka and Ross Oke, both adoptees themselves, have also been assertive in raising the issue. The two currently lead Truth and Reconciliation for the Adoption Community of Korea, or TRACK, a Seoul-based advocacy group for adoptees’ rights. The group has worked with other human rights groups, including Save The Children, to ask the Ministry of Health and Welfare last month to open an investigation into Hyunsu’s case.

They urged the government to ask itself whether it had done enough to find him a Korean family before approving his overseas adoption.

Adoptee groups say the intercountry adoption of children like Hyunsu, who was born prematurely with hydrocephalus, must be stopped.

“It is hard enough for a child to adapt to that kind of particular environment. To do that to a child who needs special care is devastating. That is not at the child’s best interest at all,” Heit said.

Holt, one of the largest adoption agencies here, has also been under fire for sending Hyunsu overseas, even though it knew that his foster mom in Korea wanted to keep him.

“Holt simply ignored my request, saying it was illegal to adopt a foster child. But I later learned that was a lie,” Hyunsu’s foster mother said in a TV interview. Holt countered that she was not “willing” to adopt him and didn’t go through the official procedures to adopt him.

Adoptee and children’s groups such as TRACK and Save The Children blamed Holt, arguing that Hyunsu could still be alive if the adoption agency had carried out a thorough background check of the family in the U.S. before he was adopted.

Activists suggested that the agency was trying to send him overseas because the money it receives for arranging international adoptions was higher than for domestic adoptions. Adoptive parents from overseas pay about $20,000 per child to agencies for arranging the process, they claimed.

Holt declined to comment on the matter.

Adoption in past, present

In the last 60 years, more than 200,000 Korean babies have been sent overseas for adoption. Korea’s international adoption began the early 1950s just after the Korean War, when the devastated country was not able to feed and raise war orphans.

But even years after the country achieved rapid economic development, the number of children sent for overseas adoption continued to grow.

The number peaked in 1986, with 8,680 adoptees leaving the country that year.

The reason that overseas adoptions were much more common than domestic adoptions for so long was because of the country’s deeply entrenched Confucian values, which puts emphasis on a pure bloodline, said Helen Roh, social welfare professor at Soongsil University. The practice of stigmatizing unwed mothers or those who raise children born out of wedlock has also played a big role in keeping the rate of overseas adoption high, she added.

“They were basically forced to give up their kids for adoption because of economic difficulties and social stigma,” Roh said. About 90 percent of Korean adoptees are born to unwed mothers, according to recent data.

The number of Korean children adopted overseas has steadily declined, falling to 755 in 2012. The Welfare Ministry expects the number to drop below 300 this year.

Roh said that the rapid decrease in the number of children sent overseas has resulted from the enactment of the Special Adoption Law in 2012.

The law requires the birth registration of babies so that they cannot be put on the waiting list of both overseas and domestic adoptions easily without sufficient information and a background check. The law also stipulates that adoptive parents must get approval from a court.

The law was passed to bring the country into line with The Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption, an international treaty that urges member countries to keep babies with their birth parents within their country of origin.

The Korean government signed the international treaty last year and is waiting for parliamentary approval next year.

The legal revision signifies a radical change in the Korean government’s policy toward adoption practices.

“Before 2012, all adoption processes were carried out easily by adoption agencies under the connivance of the government. I could say that the government was effectively encouraging the agencies to send children overseas,” Roh said.

“But the law forced the government to step in and reset its policy goal with the aim of upholding children’s human rights,” she said.

The government has not made an official announcement, but with Hyunsu’s case and protests from adoptee groups, the Welfare Ministry is reportedly planning on a wide range of changes to its adoption policy, according to an official who declined to be named.

Recent reports also say that the Welfare Ministry will soon obligate adoption agencies to carry out one year of post-adoption services, such as home visits and reports.

Scars unhealed

Thousands of adult adoptees have returned to Korea in search of their identities and birth families. But they often discover that the circumstances surrounding their adoption were dubious.

In the past, babies were often taken to adoption agencies without registrations that contain basic information about them and their birthparents. That made it easier for adoption agencies to send children overseas for many years, but it made it nearly impossible for adoptees to find their birth families in Korea. The success rate of Korean adoptees finding their mothers in Korea is 2.7 percent.

Heit claims that her records were falsified by Holt.

Calling herself a “paper orphan,” she said the agency had made her an orphan on paper in order to make the adoption process easier and less time-consuming.

“The reason why my record was falsified was in order to send me without my mother’s consent,” said Heit, who eventually found her birth mother after Korean media publicized her story.

“The adoption agencies should have said ‘no, we cannot accept these children without consent from the mother.’ But they didn’t.

“Instead they got rid of the information without my mother’s consent. That is a human rights violation. That is child trafficking.”

Activists for adoptee rights and welfare experts say that adoption should be a last resort.

“It is now time that we no longer depend solely on adoption, but search for family preservation solutions,” TRACK’s Ross Oke said in a recent TV interview.

Adoption creates traumatic experiences for children and the pain continues throughout their lives.

“It is not like studying abroad. There is so much lost when you are adopted,” Heit said.

“I was cut out from my Korean family. I was cut out from my Korean background. Even though they were no longer there, and I didn’t know anything about it, it still hurts, constant pain,” she said, comparing her experience to losing a limb.

To prevent another case like Hyunsu’s, experts say the government should increase financial support to unwed mothers so that they can keep their children.

The government offers 70,000 won per month to unwed moms who are in poverty. The cash grant is even lower than the 150,000 won and free health care that adoptive parents get.

“I think this is ridiculous. The system is forcing moms to separate from their kids,” Roh said.

By Cho Chung-un (

christory@heraldcorp.com)

Lee Hyun-jeong and Suh Ye-seul contributed to this article. ― Ed.

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)