Seoul, at first glance, is not a city where you would expect to experience abundant agriculture. The megacity is filled with highly sophisticated urban features including advanced IT technology, an extensive mass transportation system and towering skyscrapers. But Seoul has been witnessing the rise of a civic movement aimed at embracing a slow but fruitful life. At the center of the movement is an army of urban farmers who are betting on a greener future for the city, rather than pursuing a faster, and perhaps easier, life.

From abandoned plots in inner city areas and plastic boxes on apartment balconies, to rooftop gardening, a number of urban dwellers are reconnecting with the earth in the heart of the metropolis. Abandoning the comforts of the city ― where groceries and supermarket chains are found on every corner ― city farmers are putting their hands in the soil, and gaining a greater appreciation for life through gardening.

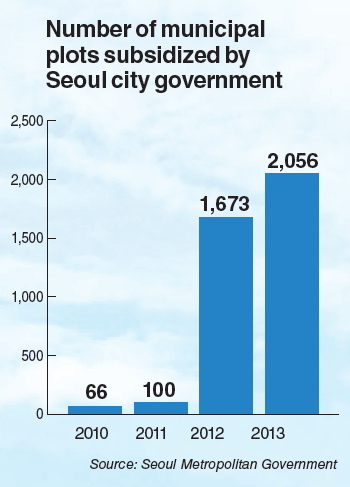

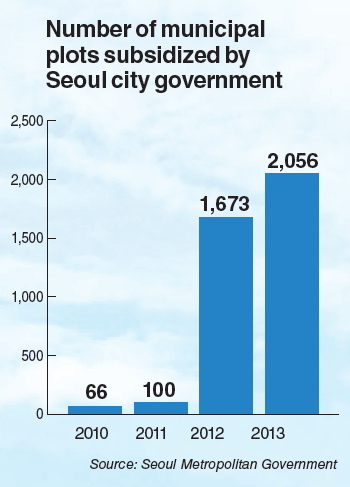

Figures provide a glimpse into the growing popularity of urban farming. According to the Seoul city government, the number of city farms surged dramatically from 66 in 2010 to 2,056 last year. Abundant media coverage also reflects this unusual interest. The number of articles published by local newspapers on urban farming surpassed the 1 million mark in 2012 from 200,000 in 2010, according to a study by local think tank Seoul Institute.

Then where is Seoul’s zeal for urban farming coming from? Ahn Cheol-hwan, representative of the Association of City Farmers in Korea, stresses the “unstoppable” human instinct to return to nature.

|

Residents of Dunchon in Gangdong-gu, Seoul, grow vegetables at a farm opened by the district office. (Gangdong District Office) |

“City dwellers have been struggling with constant social unrest. The recent popularity of urban farming reflects the human desire to regain peace by reconnecting with the earth,” said Ahn, who presented himself as a gardening mentor.

The desire has existed ever since people were forced to adapt to city life following the urban migration from agricultural regions. But a number of food scares that hit the country must have pushed people to pursue a healthier life and safer food, experts say.

In 2008, the fear of mad cow disease, or bovine spongiform encephalopathy, haunted Korea, after the government agreed to reopen the market to U.S. beef without prior consultation with the public. The risk was low but media reports at that time exaggerated the danger of the disease. In the following year, the country was hit again with a severe price hike on cabbage, the main ingredient of kimchi, due to a poor harvest.

“The interest in urban farming has been growing as an alternative method to counter problems with climate change and energy shortages as … people (are) seeking healthy and safe food,” Lee Chang-woo, senior researcher at Seoul Institute, said in his report published last year.

The interest in city farming grew further after Park Won-soon, an ardent advocate of the green lifestyle, became major of the city.

In 2012, Park, a former civic lawyer, declared the year to be the beginning of an urban farming era and unveiled a comprehensive package to secure enough farming space in the highly congested capital.

“I believe that urban farming can successfully take root in Seoul, all the more because it is such a densely populated concrete jungle,” he said, announcing a plan to allocate 2.4 billion won to support various initiatives and projects. “Seoul can become the world’s No. 1 farm city,” he said.

Under Park’s vision, the total size of urban farms in the city grew threefold in 2012 to 84.2 hectares from 29.1 hectares in 2011. The number of city farmers also surged to 440,000 from 287,000.

Officials say that the goal of the city’s urban farming project is to encourage people to grow what they need near their homes. It could also help the city create related businesses, such as new markets for food produced in the city and, most importantly, jobs.

“Urban farming can create new jobs, if developed within a full industrial aspect. Because it can raise new hopes for the city’s young people struggling to find jobs,” a city official said.

By Cho Chung-un (

christory@heraldcorp.com)

![[Herald Interview] Technology innovation leads future of Korean agriculture](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=605&simg=/content/image/2014/03/28/20140328001772_0.jpg)

![[Herald Interview] 'Trump will use tariffs as first line of defense for American manufacturing'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/26/20241126050017_0.jpg)

![[Exclusive] Hyundai Mobis eyes closer ties with BYD](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/11/25/20241125050044_0.jpg)