Globalization, demographic change and economic growth have led Korea to embrace cultural diversity and tolerance toward others. But biases and discrimination against foreigners remain and Koreans’ pride for ethnic purity is deeply entrenched. This is the last in a 10-part series that offer a glimpse into the nation’s efforts to promote multiculturalism and challenges in immigration law, education, welfare, public perception, mass culture and more. ― Ed.

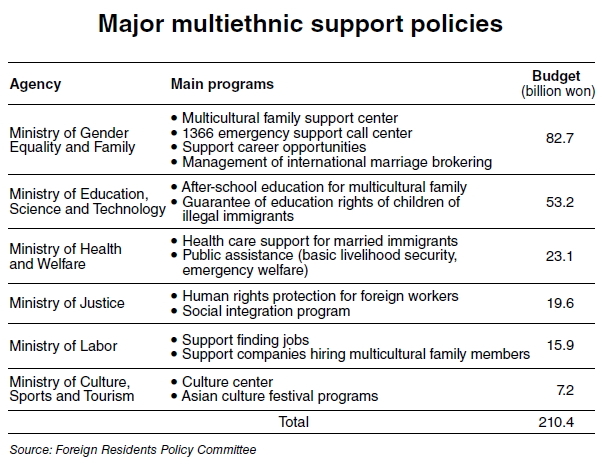

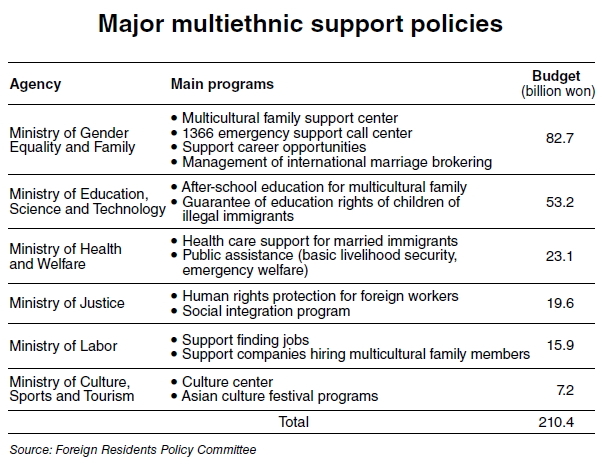

For the past decade, the Korean government has implemented a range of policies designed to help immigrants adapt and access education and social services.

From language classes to job training and cultural programs, the measures aim to help Korea cope with its increasingly multicultural population.

But the nation is still in need of a body to coordinate policies dispersed among government branches including those related to immigration, anti-discrimination, human rights, education and health care.

They also call for broader state and civilian efforts to embrace diversity in everyday life and truly accept migrants and non-ethnic Koreans as genuine members of the community.

|

A bride goes through a group Korean traditional wedding ceremony at Seocho Culture and Arts Park in southern Seoul on May 22. The event was held for migrant spouses who did not have a wedding ceremony. (Yonhap News) |

Many experts criticize the current multicultural policies for failing to effectively serve immigrant spouses and their families.

“They are actually implemented to force foreign brides to become an alternative force to tackle the nation’s fast-declining birthrate,” said Kim Hyun-mee, a cultural anthology professor at Yonsei University.

“The Korean government’s policies on multicultural communities are based on the ‘patriarchal family-oriented welfare model’ that subordinates immigrant spouses to a traditional belief system that urges women to keep themselves loyal to their husbands and limit their roles to housekeeping and childbirth,” she said.

These policies were implemented by the Korean government because it strongly believed that welfare packages could help immigrants accept Korean culture and act like Koreans, the professor stressed. But this one-way policy brought adverse reactions from native Koreans as they started to view multicultural families as vulnerable social groups, not equal citizens.

“Multicultural families have become major beneficiaries of the government’s welfare programs and the businesses’ corporate social responsibility projects, even before they tried to make social, cultural and psychological exchanges with Koreans,” Kim said.

“We need to discuss whether these policies and perspectives have built another social hierarchy and segregated immigrants,” she added.

First of all, she said, the Korean government needed to stop labeling them “damunhwa,” meaning multicultural in Korea.

The government’s frequent use of the word has created a negative image of multicultural families, Kim said.

“The word damunwha would rather place a severe social stigma on children born to international couples for their rest of lives,” she added.

The government should start promoting a “positive, empowering and independent” image of immigrants.

“There is a need to educate the media and the entire education system in Korea to eradicate discrimination and the stigma attached to marriage migrants, promoting a positive and empowering image of marriage migrants such as Lee Jasmine,” said Jean Encinas Franco, a political science professor at University of the Philippines.

The government should also draft new immigration policies that incorporate cultural reciprocity

“Integration is not only a process of migrants respecting the community and fulfilling responsibilities and obligations as citizens, but also a reciprocal process where existing residents in receiving countries accept migrants and respect and tolerate differences and diversity, helping them become part of the society,” said Shin Ji-won, IOM Migration Research and Training Center.

Experts also called for a new immigration office that could effectively manage and coordinate the relevant policies.

“An office or department dealing with the foreign resident policy should be installed and operated under the Office of the Prime Minister and in the long term, the establishment of an immigration office should be actively prepared,” said Kim Joon-sik, head of Asian Friends.

Other experts said the current policy put too much focus on multicultural families formed through international marriages and did not consider other types of migrants, such as short-term migrant workers.

“Short-term migrant workers make up a large portion of the migrant population in Korea. But the current social integration policy for immigrants mainly targets immigrant spouses,” Shin said.

According to Ministry of Justice, Korea had about 547,000 migrant workers on short-term visas as of 2011, more than twice the number of marriage immigrants, 205,352.

“The government needs to pursue an integration policy that embraces a more diverse range of immigrant groups,” she said, adding that migrant workers in Europe chose to settle down and brought significant demographic change.

Migrant workers are living in dire poverty and their human rights are being infringed because of the absence of legal protection.

“Short-term migrant workers are only allowed to stay for a strictly limited length of time, and cannot change their workplace, which makes them one of the most marginalized groups in society,” she added.

Foreign experts also raised problems involving citizenship for migrant wives, saying the process is “completely dependent on their husbands’ opinion.”

Foreign brides can acquire citizenship after two years of legitimate marriage with their husband’s consent. Those who get divorced before acquiring citizenship become illegal aliens and must leave the country.

“The government should revise some points about granting citizenship for foreign brides. If not, they will become victims of domestic violence because the husband and their family have strong influence in the final decision of whether she obtains citizenship,” said Nguyen Thi Hong Xoan, a sociology professor at Vietnam National University.

The number of divorce cases among Korean husbands and Vietnamese wives grew from 28 cases in 2003 to 1,992 in 2012. The women are mostly forced to leave the country, leaving their children behind.

“The government should provide legal support to divorced brides so they can stay in Korea, close to their children who will most likely be living with their fathers after divorce,” she said.

By Cho Chung-un (

christory@heraldcorp.com)