Globalization, demographic change and economic growth have led Korea to embrace cultural diversity and tolerance toward others. But biases and discrimination against foreigners remain and Koreans’ pride for ethnic purity is deeply entrenched. This 10-part series will offer a glimpse into the nation’s efforts to promote multiculturalism and challenges in immigration law, education, welfare, public perception, mass culture and more. ― Ed.

Korea is one of a few countries that have long remained racially homogenous. But a growing number of immigrants since the late 1990s have prompted the nation to embrace multiculturalism as a key national policy and cultural movement.

It is no longer rare to see mixed-raced children mingling with Korean peers at schools and streets. More Koreans marry foreigners and immigrants are playing an increasingly big role in society. The nation now has its first foreign-born lawmaker representing ethnic minorities.

Despite diminishing prejudices and discrimination against the newcomers, Korea still has a long way to go with its immigration laws, education and welfare policies and people’s tolerance toward different cultures, experts say.

It is too early to jump to the conclusion that Korea has made a successful entry toward a multicultural society, said Kim Yi-seon, research fellow at the Korean Women’s Development Institute.

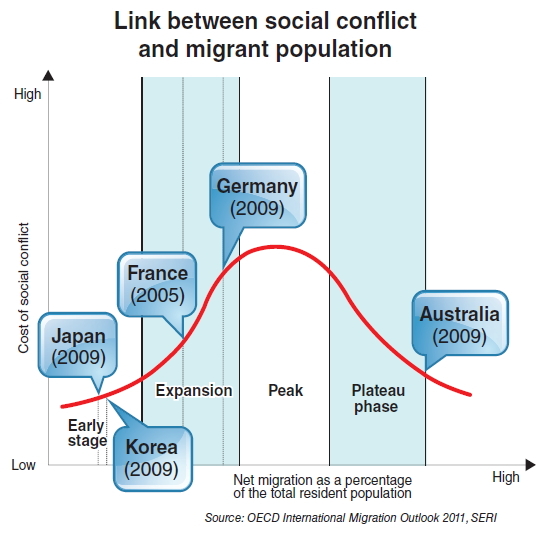

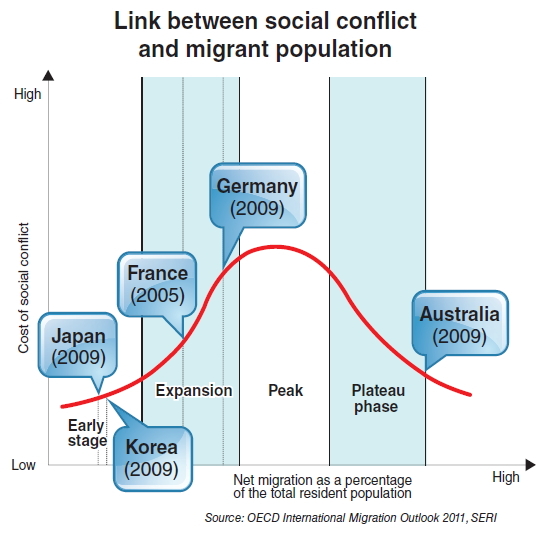

Compared to other European countries, including France and Germany, Korea is still in the very early stages of being a multicultural society.

“Not only Korea but also the Korean government is at an elementary level when it comes to talking about its immigration policy,” said Kim.

|

Immigrant spouses and their children from Boseung and Gangjin, South Jeolla Province, attend a cooking class on Korean traditional food held at Sookmyung Women’s University in Seoul on March 29. (Yonhap News) |

Immigrants have existed in Korea since the early 20th century when ethnic Chinese moved to the Korean Peninsula and had mixed-race children after the 1950-53 Korean War. But the government didn’t pay attention to them because the number of immigrants in society back then was so low.

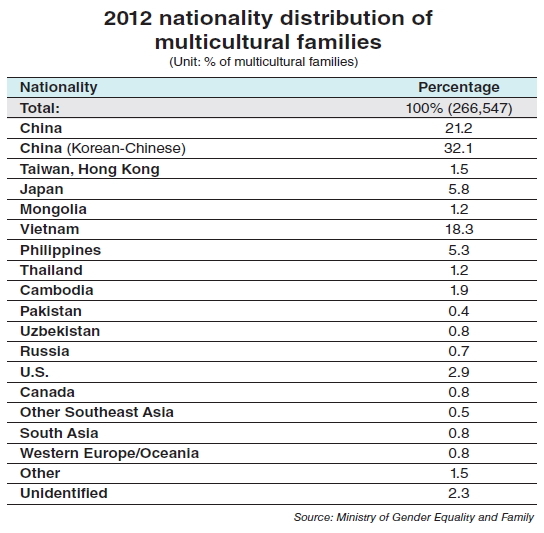

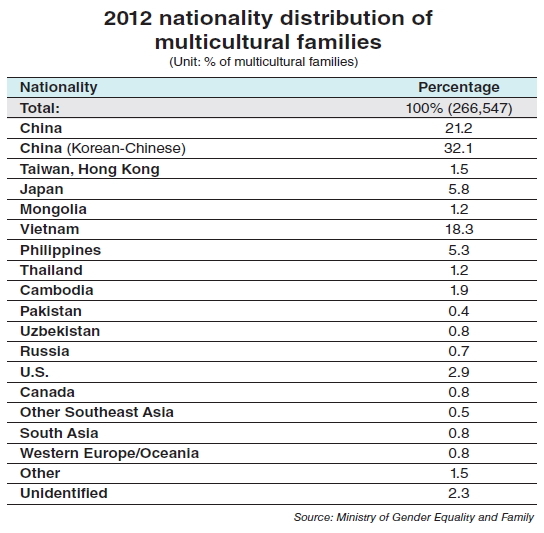

The rapid inflow of immigrants through international marriages, largely from Southeast Asian countries, started in the late ’90s leading the government to devise measures to help them settle down.

The number of multiethnic families ― mostly consisting of immigrant spouses and children ― reached 550,000 in 2011, a nearly 60 percent increase from 340,000 in 2008.

The Korean government expects the number of multicultural families to reach 1 million by 2020 and the proportion of families with diverse cultural backgrounds to double from 1 percent of the Korean population in 2011 to 1.9 percent in 2020.

Korea’s transition into a multicultural society will not be smooth, if other countries’ histories are a guide, Kim said. European countries like Germany and France, which embraced multiculturalism and implemented various immigration policies many years before Korea, have recently declared that their policies have failed to stop social conflict involving immigrants.

Experts say, therefore, it is important to increase social acceptance of the government policy on immigration and how far it has to cover.

“If social acceptance increases, side effects from multiculturalism under fixed policy expenses will be reduced and the efficiency of policy spending will be increased,” said Kim Jeung-kun, a research fellow at Samsung Economic Research Institute. Establishing a long-term vision for Korea as an immigrant state is also needed, he added.

It is somewhat surprising that the Korean government started to take the immigration issue seriously only in 2006. At that time, then-President Roh Moo-hyun was under pressure from the international community to address concerns about Korea neglecting human rights issues involving immigrants and foreign workers and brides. The fear of losing the productive population in the future due to a record-low birthrate was another reason. But it was the visit by American football star Hines Ward that dramatically turned Koreans toward a multicultural society.

Ward, born to a Korean mother, became a proud son of Korea and inspired many that people from a multicultural background could also become an important asset to the country.

But it took four years for the government to launch the first phase of the comprehensive multicultural project. The 2010 plan focused on supporting them financially and institutionally. Critics said that the initial plans led many Koreans to build a new type of prejudice against multicultural families.

“The plans gave the idea that multiethnic people are those who need help, ignoring their capabilities and potential to make a contribution to society,” said Kim of the Korean Women’s Development Institute.

Late last year, the government again announced the second part of its policy efforts that focused on improving education, eradicating discrimination and supporting their social and economic participation.

The new support measures focus on providing better educational opportunities for children from multicultural families and offering job opportunities for immigrant spouses to help them become part of society. The government seems to have made progress in the second plan because it includes supportive measures for families of foreign workers and students as well. Those who are legally recognized as foreign residents here have been excluded from the government’s support programs so far.

“The second part of the comprehensive plan is designed not only for immigrant spouses but also for their families who share different cultures under one roof. (The government) needs to gain public acceptance of the project because it is a must, not a choice, for our society,” said former Prime Minister Kim Hwang-sik, who then chaired a governmental committee that devised 86 projects under six different categories on multiculturalism for the next five years. The government-led support toward multicultural families is likely to increase as the country’s new President Park Geun-hye has pledged to make beneficial institutional changes for ethnic minorities.

Many Koreans also agree that Korea embracing cultural differences and accepting immigrants as part of society is the right thing to do.

As society becomes more competitive, however, Koreans could feel a greater sense of deprivation if immigrants start to get more jobs or enter mainstream society, as did Lee Jasmine.

“I don’t feel good if I or my children would have to compete with immigrants for a limited opportunity,” said Jung Hye-won, a 32-year-old office worker in Seoul.

Han Kyung-koo, an anthropology professor at Seoul National University, said Koreans would also experience chaos in the transition to a multiethnic society.

“Like immigrants feel that they are strangers to the Korean society, the multiethnic society itself is also an unfamiliar phenomenon for many Koreans,” said Han.

“Koreans also need to adapt themselves into the emerging multiethnic society through cultural education that protects individuals’ rights and choices, and develop their ability to negotiate and compromise,” he said.

By Cho Chung-un (

christory@heraldcorp.com)