A decade ago, history textbooks in Korea started to refrain from saying that Korea is a mono-ethnic country, as state-wide controversy about the cited phrase can prompt racism against ethnic minorities in the country.

While the widespread belief that Korean people are of single ethnicity has been challenged and debunked -- for the most part -- over years, insensitivity toward actions or words that may be offensive to other ethnicities continue to ail Korean society.

Earlier in the year, comedian Hong Hyun-hee was embroiled in a dispute after she dressed as an African native acting in a comedic fashion. Australia-born comedian Sam Hamington commented that it was a “disgrace,” and berated the comedic sketches that belittle ethnic groups.

Hong issued a public apology a week later, but incidents surrounding cultural insensitivity continue to pop up.

Last month, creators of MBC drama series “Man Who Dies to Live” apologized for their controversial -- and grossly inaccurate -- depiction of Islamic culture. The show issued a public apology a few days later.

|

A scene from MBC drama series “Man Who Dies to Live,” depicting what appears to be Islamic culture. (MBC) |

“Avoiding any sort of racial prejudice is something that should be very natural, and yet is often ignored in Korean show business,” said local movie director and culture critic Cho Won-hee, saying such depiction derived from lack of contact and feedback with foreign cultures.

There is only a limited type of Korean pop culture that is exposed to the outside world -- such as K-pop and romance-driven TV dramas -- and while they are popular, many genres of the pop culture is still quite isolated within the country, such as comedy.

“This (cultural insensitivity) does happen all over the world so the creators of the shows don’t need to obsess over it. But they do need to keep in mind that it is a very serious issue that needs to be worked on,” said Cho.

In many cases, the racial prejudice spills over to affect minor ethnic groups living in Korea.

Georgia Scott, a writer and English teacher who had lived in Korea, said that she was denied an entrance to a jjimjilbang -- a mixture of sauna and a public bathhouse widely used in Korea -- just because she was black. She noted that this sort of incidents often happen in rural areas, in her case in Ilsan, a satellite city of Seoul.

As in the case of Scott, racism in Korea tends to hit non-Caucasians in the country even harder. It is hardly a secret that jobseekers who are not “white” in Korea have a harder time getting hired.

In June, Kislay Kumar’s story of being denied entrance to an Itaewon bar because of his ethnicity -- being Indian – sparked a furious reaction online. The bar later denied having any knowledge of such discriminative action.

Lita Collins, an American of Asian descent, said that she never heard from her recruiters after sending a photo.

Earlier in the month, a recruitment post looking for English teachers was posted on Seoul Craigslist, with a phrase “No Black,” which obviously prompted furious reaction from the expat community here.

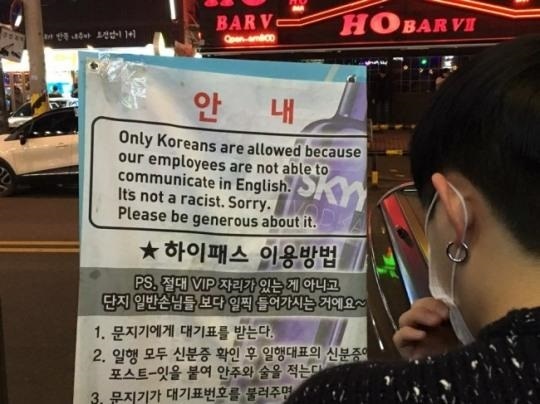

|

A sign at a bar in Hongdae in Seoul says that only Koreans are allowed in the venue in this 2016 file photo. (Ock Hyun-ju/The Korea Herald) |

Despite continued efforts by both the government and civilian sector for Korea to become a multicultural society, many of the Koreans appear to be reluctant toward embracing other ethnic groups.

Last year, the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family revealed a survey that showed 31.8 percent of the respondents “did not want foreigners or migrants as their neighbors.” About 60.4 percent thought that employers should hire Koreans first, should jobs become rare.

A 27-year-old African-American woman -- who wished only to be identified as L.C. -- said she came across such discrimination while working at a local language school in Osan, Gyeonggi Province.

She said that she encountered various acts of racism while teaching 6-year-olds, with one student saying that she was “ugly because she’s black.”

Evidence indicates that racism in Korea is still a very real thing.

It was only last year that Korean-only bars in Hongdae, Seoul sparked controversy. It was only a few months ago that rapper Tamil was berated publicly for using “n---- (racial epithet)” in his lyrics. It was only last month that a ridiculous depiction of Arab was aired on national TV.

The way the general public approach these issues, however, indicate that wind of change may be imminent. Instead of joining in the "comedy," tweets and messages by locals have spread to prompt public apologies for perpetrators of such acts.

“At one point, we would always realize that we are somehow racist. I am, too, based on certain experiences with certain ethnicities or races. But it won’t stop me in believing in a second chance,” said Collins. “It has to start somewhere to break the vicious cycle (of racism). It’s good that people start to be made aware of the problem.”

By Yoon Min-sik

(

minsikyoon@heraldcorp.com)