Striving to shed its reputation as a major exporter of children overseas, Korea recently tightened its law on adoption to ensure stricter state control, a transparent process and better protection of adoptees.

While the new regulations are hoped to help stem the child trade in disguise and human rights abuses, concerns are growing over their unintended consequences in a society that highly values blood relations and deems out of wedlock births shameful.

Some fear that the new law will lead to illegal backdoor adoptions involving those who want to avoid the stigma of being a single mother or adopting a child.

Under the Special Adoption Law, which came into force in August, adoptions are put under stricter control of the state and the courts.

It requires the government to keep a central database of adoptees and gives the family court authority to approve adoptions instead of state-designated non-governmental agencies. Parents who want to give up their children must register them with the state in advance.

The nation is also seeking to join the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption designed to protect the human rights of children adopted overseas.

The new law was promoted by a group of Korean adoptees and lawmakers so that adoptees can be sent to better homes and later find their adoption records more easily. It passed the National Assembly in June and took effect Aug. 5.

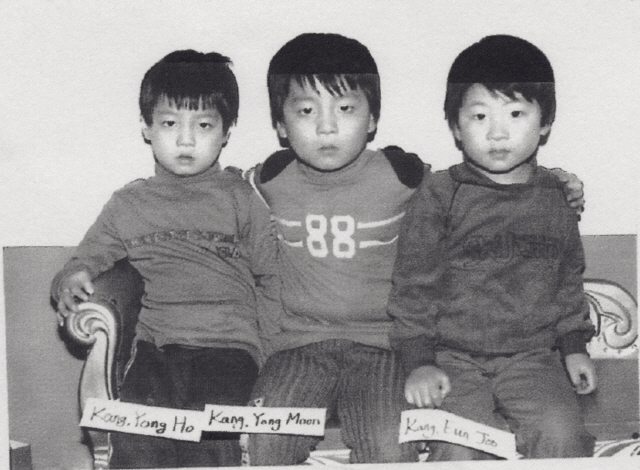

Adoption cases from the past were fraught with falsified family records, done in order to circumvent an American regulation that states only orphans be eligible for adoption.

Adoption agencies had admitted to occasionally creating new registries for adoptees because many children were abandoned, and they were unable to track down the birth parents for consent. Using such methods, the number of international adoptions in Korea has reached over 164,000.

Additionally, international adoptees have long criticized lax adoption policies resulting in citizenship problems, as well as inadequate information regarding their birth and adoption.

Two months after the new adoption law took effect, adoption agencies and parents are still assessing how the changes will affect them and the children being adopted.

There are concerns that despite its intention, the stricter law is out of synch with Korea’s attitudes regarding single mothers and adoption.

Choi An-yeo, head of the Domestic Adoption Team at Holt Children’s Services, said that despite the change, adoption agencies would retain most of their role, such as counseling and workshops for adoptive parents and children.

“The final decision is made by the family court, but nothing changed much except you send documents to the court to wait for a verdict,” Choi said.

On the other hand, Kim Hye-gyeong, head of the Department of Family Support at Eastern Social Welfare Society, said she was unsure how the special law would affect them and found the transition process confusing.

“We sent a document to the family court for a permit exactly according to the guidelines, but were asked to make revisions,” Kim said.

Both adoption agencies were supportive of changes regarding adoptive parents. Adoptive parents will now have their financial means assessed, as well as undergo drug and alcohol addiction tests. The mandatory adoption education period also doubled from 4 to 8 hours, all of which is documented and sent to court.

Kim said that although documentation has become more complicated, the agency welcomes the tightening of the selection of adoptive parents.

Choi also said that while some feel uncomfortable, more parents submit documents and attend education workshops without protest.

“Seventy parents took the education workshops since the law changed, and although it was more taxing, they said it helped them better prepare for adoption afterward,” she said.

To ensure transparency, birth mothers must now register the baby before giving them up and adoptive parents must register the child as “adopted” in order to carry out the adoption process.

Although the child’s records transfer from the birth mother’s to the adoptive parents’ registry post-adoption, birth mothers fear the long adoption process and attending family court could expose their identities.

“Birth mothers feel uncomfortable because they fear (registering their baby) might stigmatize them for life,” Kim said.

An SBS article in September reflected the fear, reporting that the number of babies arriving at Holt dropped from the monthly average of 64 to 31 in August. Other agencies experienced a similar drop.

Meanwhile, a “baby box” where mothers can leave unwanted babies has seen an increase in abandoned babies, with mothers leaving notes saying they have nowhere else to go because of the special law.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare responded that the decreased number of babies was a temporary occurrence, and they expected adoption request rates to normalize once the new law settled.

In addition to birth mothers fearing social stigma, concerns have also been raised on the new law increasing backdoor adoptions. As Korean society still views adoption with prejudice, some adoptive parents feel uncomfortable about open adoptions.

“Most people who domestically adopted did so in secret, where they registered adopted children as their own on the family registry,” Choi said. “But under the new law that would be impossible as all adoptions will be open.”

In response, revisions have been made to the law. An example is that when adoptees ask for their centralized adoption records, they will now only view their birth parents’ last names instead of their full names and other personal information.

But there will have to be further societal changes for adoption conditions to improve. Choi echoed public criticism that support for single parents was inadequate compared to the new law limiting their choices.

The number of single mothers in shelters increased from 2,442 in 2005 to 4,074 in 2010. However, many are below the poverty level, as data from the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family showed that the average monthly income of a single mother with a child was 785,000 won in 2010, which was less than the minimum cost of living in a two-person household for 2011, 907,000 won.

Additionally, according to Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, 34.4 percent of single mothers decided to give up their children for adoption because they “lack economic means,” followed by 29.8 percent responding, “for the child’s future”.

Despite this, the government only provides minimum aid for raising children.

“As more single mothers raise their children, the government should provide more support so that they can raise children without problems,” Choi said.

Choi also said that the public perception needed to change for adoption laws to be more effective, pointing out that most domestic adoptive parents still desire non-disabled baby girls.

Kim said that the purpose of adoption is for children to find homes as soon as possible, and expressed his wish that policies were geared toward successfully sending children to homes.

“There have only been a small number of adoption requests received since the new law revisions, so we have to wait and watch for any definitive results,” Choi said.

By Sang Youn-joo (

sangyj@heraldcorp.com)