Vote on school meals to be watershed for Oh’s political future, welfare competition

Against the backdrop of a pile of boxes containing what he had awaited for months, Seoul Mayor Oh Se-hoon stood before a crowd of reporters at City Hall on June 16.

“The upcoming referendum will be a watershed to decide whether to expand or put an end to welfare populism,” said Oh. He hoped the judgment to be made by Seoul citizens would ring alarm bells against the “flood of populist pledges.”

Earlier in the day, representatives from an association of conservative civic groups had delivered to the city office three truckloads of boxes filled with signatures from more than 800,000 citizens calling for a referendum on free lunches for all elementary and middle school students.

|

Seoul Mayor Oh Se-hoon addresses a news conference in front of boxes filled with signatures calling for a referendum on free school meals at City Hall earlier this month. (Yonhap News) |

By undertaking the work to prepare for the vote, the mayor also put his political future at stake as he has been casting himself as an antipopulism fighter by highlighting his objection to the unlimited offer of free school meals, which is being pushed by the city council dominated by the main opposition Democratic Party. The referendum will ask citizens to choose between the council’s scheme and a gradual extension of free lunches to cover students from the 50 percent lowest-income families as suggested by the mayor from the ruling Grand National Party.

If he succeeds in thwarting the full-scale free lunch program, Oh will consolidate his position as a principled leader, attracting the conservative electorate who raise their eyebrows at the unfettered competition between the rival parties to woo voters with populist pledges. A win in the referendum, which is expected to be held in late August, would also heighten his stature as potential presidential runner.

Some critics say Oh, 50, has been deliberately making a high-profile political issue of the free lunch program. Since the council passed an ordinance on implementing the program in December, Oh had boycotted its sessions for more than half a year. He attended council meetings last week, arguing with opposition councilors over the referendum and other municipal policies.

“Mayor Oh is apparently using the vote as a stepping stone for his bid for the presidency,” said Kim Dong-wook, a DP council member.

Oh has rebuffed the claims he has ulterior motives as an attempt to distort his sincerity to uphold conservative values. He has been touted as potential presidential candidate since he was first elected as Seoul mayor in 2006 after serving a four-year term as a lawyer-turned-lawmaker, spearheading a drive to reform the GNP and initiating the revision of the election law to make political funding more transparent. Some observers say he may join the race for the GNP presidential nomination next year if his stance is consolidated in the wake of the referendum win. But most commentators see his serious presidential challenge will come five years later. Oh recently told a local daily that he does not mind some people saying he lacks willpower. “I am young, so there is no need to hurry,” he said.

If voters go for the council’s free lunch program or the referendum itself becomes invalid with less than a third of eligible voters turning out, the mayor may suffer an irreparable setback, drawing criticism he has wasted 18 billion won ($16.6 million) in taxpayers’ money for his “political gambling.” He will come under mounting pressure to step down and even if he stays in his post, he will stagger through the remaining period of his second four-year term that began in July last year.

In the June 16 news conference, Oh said he would accept the result of the plebiscite but stopped short of placing his mayoralty at stake by saying he would “consider what political responsibility to take.”

Oh recently reiterated he was ready to take full responsibility for loss in the referendum, saying he will make public his concrete ideas before the referendum is held.

Difficult choices

Aside from Oh’s political fate, the vote is also drawing keen attention from the public as its outcome will set the tone for the escalating competition between the ruling and main opposition parties to present welfare pledges in the lead-up to next year’s parliamentary and presidential elections. The mayor has said if the free lunch program is dismissed in the referendum, both parties will have to change their current election strategies relying on measures to court voters with welfare populism.

Political commentators note the referendum is pushing the rival parties into a difficult choice.

The GNP, which has supported Oh’s fight against the DP-dominated city council, is now in no position to go all-out to win the referendum. Many GNP lawmakers are worried that campaigning for the plebiscite may overshadow their efforts to woo voters by polishing up welfare measures.

A day after Oh’s news conference, Rep. Nam Kyung-pil, a four-term lawmaker who is running for election as party leader at the national convention next month, urged the mayor to give up his referendum push and seek a compromise with council members.

The mayor also faced a lukewarm response from GNP floor leader Hwang Woo-yea during their meeting on June 20. Noting the referendum was a municipal issue, Hwang said it would be difficult for the party central office to be involved in the campaign for the referendum, exacerbating the strife with the opposition party.

While heaping criticism on the mayor, DP members also appear undecided on how to cope with his referendum drive. Some argue for making the vote invalid by keeping the turnout below a third of eligible voters. “The referendum will only serve Oh’s political purpose,” said Kim, the DP councilor. “In this circumstance, it may be a better option to shun voting.”

But others including progressive activists say such a passive response will only boost the mayor’s stance, demanding an active participation in the vote to push through free lunches for all students.

Voter turnout

For the outcome of the referendum to be valid, more than a third of 8.36 million eligible voters in Seoul ― or at least about 2.78 million voters ― are required to cast ballots. A simple majority is needed to determine the result.

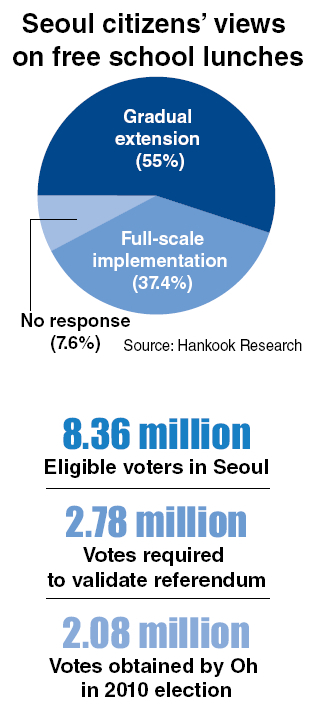

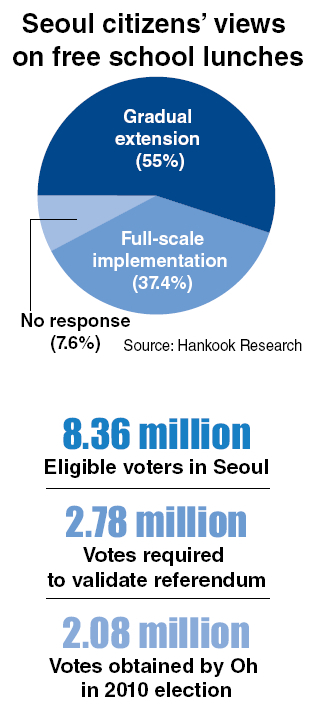

Aides to Oh express confidence that the mayor will emerge victorious out of the referendum if over a third of voters go to the polls. In a survey of Seoul citizens in January, about 65 percent of respondents supported the gradual extension of free school meals. A recent poll by Hankook Research showed 55 percent of Seoul citizens to be in favor of an incremental approach, compared to 37.4 percent for full-scale implementation, with 7.6 percent giving no response.

A senior official at City Hall, who requested anonymity, expected the turnout to be above the required level as public interest grows with the referendum day drawing nearer. The official said the referendum might be transformed into a vote of confidence in the mayor, rallying his supporters. The coalition of civic groups supporting Oh, which launched the petition campaign in February, had collected signatures from more than 801,000 citizens, nearly double the required number of about 418,000, or 5 percent of Seoul citizens aged 19 or above.

The referendum is expected to be held around Aug. 20 after work to scrutinize the validity of signatures and a final deliberation by an 11-member independent panel consisting of lawyers, professors and other experts.

Noting the referendum takes place before the summer vacation season is over, some political observers say it is not assured that more than a third of voters will come to polls on a weekday. Oh gained 2.08 million votes when he won the mayoral race against DP contender Han Myeong-sook in the local elections last year with the turnout at 54 percent. A mere 15.4 percent of voters cast ballots in the 2008 election to select the head of the Seoul education office, which was held amid a sharp confrontation between the conservative and liberal camps.

Diverse sentiments

Interviews with some Seoul citizens show their sentiments on free school meals are varied and not simply divided between income brackets.

A 40-year-old owner of a jewelry shop in downtown Seoul, who wished to be identified by his family name Han, said it would be fine with him to provide free school meals for all students. “Children in that age group are very sensitive to how they are viewed by their peers. So I think it is worth the money to make no distinction in offering free meals,” said Han, adding that his view should sound more objective as he himself has no children.

A female bank executive surnamed Kim, 45, whose children attend middle and elementary school, said she supported Oh’s idea. “The cost may not be too much. But I don’t think it is a wise way to use taxpayers’ money to give free lunches to children from wealthy families as well as those from less privileged families.” She said methods could be found to prevent possible disharmony between recipients of free meals and schoolchildren with parents who could afford to pay.

Park Kyu-hong, 72, a retired businessman, also sided with the limited offer of free lunches. “I don’t believe it makes sense to use money to give free meals to children from wealthy families when the money can be spent for more urgent purposes.”

A middle-class housewife in her 50s, who wished to remain anonymous, said.: “I don’t like the idea of providing free lunches for all students but I also don’t think it is a matter the Seoul mayor should have so adamantly opposed.”

By Kim Kyung-ho (

khkim@heraldcorp.com)