The fabricated cloning research by Hwang Woo-suk in 2006 remains a painful memory for Koreans, who had taken pride of their nation’s edge in a field that promised to transform medicine.

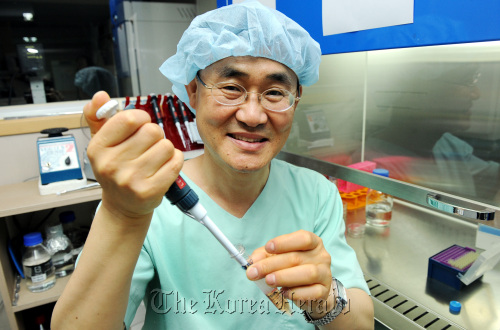

No one agonized more over the fraud case than Park Se-pill, Korea’s top stem-cell researcher. Research in the area was brought to a virtual standstill as the government cut funding, studies based on human eggs were banned, and ethical controversy gripped the public and media. Even the most scrupulous Korean scientists faced doubt and scrutiny from the global scientific community.

Five years later, the embattled science appears to be recovering with Park and colleagues playing a key role.

His team succeeded in cloning a rare cow on Jeju Island. He became the world’s third person to achieve techniques to coax ordinary cells to work as stem cells that could grow to form different body parts. His research has also been used to make a hit beauty product ― an anti-aging cream that is claimed to rejuvenate skin tissues.

Despite the uproar stemming from the Hwang scandal, Park has taken no step back from his belief in stem cells’ potential as a solution to incurable diseases and genetic defects.

But the impact was enormous, leaving behind high institutional barriers that still pose a threat to the country’s scientific advancement.

“Despite our technologies, we can’t make progress because of difficulties in obtaining approval for embryonic stem cell projects,” Park told The Korea Herald.

“Of course, Hwang was at fault in the first place at a time when the government was actively backing his cloning projects, but the case brought too serious repercussions.”

After 12 years working at a leading infertility medical center, Park began his own research at Cheju National University in 2005, and launched a venture firm named Mirae Biotech in 2006 with assistance from Konkuk University, his alma mater.

His projects involve embryonic stem cells, adult stem cells and the so-called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS).

In June last year, Park’s team at Cheju cloned a black cow from a frozen cell, which the scientists took a decade ago from a now dead animal.

“Black cows indigenous in Jeju are becoming extinct,” Park said. “We stored somatic cells of the most superior cow, which then cost 200 million ($185,800) won in the market.”

It was solace for local livestock farmers when hundreds of thousands of cattle were slaughtered due to the nation’s worst outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease.

In a joint project with the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, his team has produced several more cows using his method that allows for the multiplication of a cloned animal. Park said he plans to start transplanting the body cells into existing cows in local farmhouses soon.

In November, Park cultured cardiac muscle cells by reprogramming skin cells, successfully practicing the iPS techniques for the third time in the world after U.S. and Japanese teams. The result raised hopes for tailored therapies for patients.

Park sought approval at the end of 2009 for a joint embryonic stem cell research project with ShinWoman’s Hospital, a major fertility clinic, but was rejected by the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

“The application process is complicated and full of bureaucratic huddles,” he said.

Some bioventure firms complain that the government applies extremely strict guidelines and requires too high a level of equipment for licensing.

Currently Cha Biotech, run by Cha University Hospital Group, is the sole institution allowed to conduct human embryonic research.

Park said despite some progress in studies involving adult stem cells and iPS cells, Korea is lagging behind other countries in cloning and embryonic stem cell research, which is partly attributable to regulatory hurdles.

“It’s a national subject ― who spearheads matters,” he said. “If a few teams including us at Mirae are allowed to carry on, we can make a leap. We’ve secured know-how in all three technologies ― adult, reprogrammed and embryonic stem cells.”

The global stem cell market is projected to expand at an annual rate of 24.5 percent to $32.4 billion next year from $6.9 billion, according to the Ministry of Education, Science & Technology.

Adult stem cells would take up more than half with $18 billion and embryonic stem cells would also grow to about $5 billion.

Advanced countries including the U.S., U.K., Japan, Singapore and Australia have been shoring up stem cell research by easing regulations, institutionalizing related procedures, establishing labs and raising funding.

But in Korea, the burgeoning field’s share of total life science investment shrunk to 3.4 percent in 2009 from a feeble 3.8 percent, the ministry reported.

In 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama put an end to a ban on human embryonic stem cells after eight years and increased federal funding.

Following suit, the Korean government unveiled a plan in July to invigorate stem cell research by boosting funding to 120 billion won by 2015 from 41 billion won in 2009, targeting one of top five leaders in the global arena.

As part of the initiative, the education ministry selected six research teams last year to transform into globally competitive leaders by each funding 1 billion to 8 billion won through 2015. But none of the winners is engaged in embryonic stem cells.

“I focus on embryonic stem cells because unlike other cells they can be mass-reproduced once you come up with a prototype, which promises high efficiency,” Park said. “Adult stem cell research has existed for decades but the cells are difficult to multiply.”

Concerns over iPS cells are also adding the weight to the importance of embryonic stem cell research.

Emerged as a therapeutic solution, iPS cells can be developed into any adult cell in the body ― like embryonic stem cells but without destroying human eggs.

But some scientists have recently found iPS cells to grow slower and die more quickly. A U.S. study showed that the reprogrammed cells preserved partial memories of their prior life as adult tissues, which could cause rejection symptoms. Other experts said iPS cells are promising enough, but could not work without help of embryonic stem cells.

“There might be an ethical problem in some case, and there might not. The point is how to develop treatments for incurable diseases as fast as we can. What’s needed is a good policy that can minimize such a hullabaloo and give momentum to the stagnated research,” Park added.

The scientist-turned-entrepreneur is now bracing for his company’s public offering, which could “sow the seeds of explosive synergy between public funds and its life-science projects.”

“As experienced by other professors in the past, we are not likely to succeed without an independent revenue source regardless of the amount of financial resources we bring in,” Park said.

In a bid to help stabilize its finances, Mirae launched its first beauty product this year called Stem Secret, which contains nutrition-rich stem cell culture fluid.

A majority of participants in clinical tests saw wrinkles around their eyes reduce significantly in eight weeks, according to the company.

“Our cosmetics have other bioactive materials including oriental herbs, aloe vera and procollagen generated in cell differentiation processes, which are all good for skin revitalization,” Park said.

By Shin Hyon-hee (

heeshin@heraldcorp.com)