LOS ANGELES ― Jeffrey Katzenberg was visiting the University of Southern California recently when a faculty member stopped to chat with him. As the two parted ways, the DreamWorks Animation chief urged him: “Just keep sending me magicians.”

The magicians Katzenberg seeks are animators, in high demand as the art form has exploded not only in movies and video games but also arenas such as medical research and cellphone displays. Higher education is beginning to respond to the need: USC awarded 18 bachelor of arts in animation and digital arts diplomas in May, becoming the first major research university to offer the degree.

|

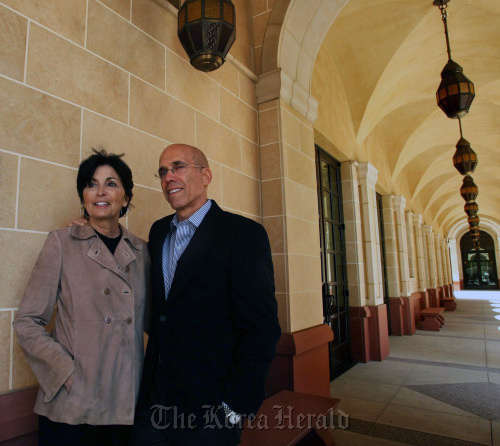

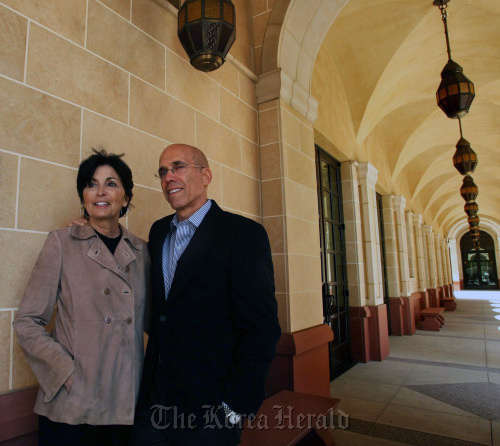

Marilyn and Jeffrey Katzenberg, CEO of DreamWorks Animation, stand outside the Marilyn and Jeffrey Katzenberg Center for Animation at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts on the USC campus in Los Angeles, California. (MCT) |

Wednesday, the school will dedicate the Marilyn and Jeffrey Katzenberg Center for Animation, a gift that helps finance and equip the school’s four-story, Italianate animation building, opened in 2010, with classrooms for learning visual effects, 2-D and 3-D animation and stop-motion.

“Animation used to be a little sideshow,” Katzenberg said. “We’re now the most successful genre in film. There’s a lot more of these movies being made and there’s a greater need for artists and skilled and trained talent to make them. This isn’t philanthropy. This is an investment in our own business.”

As the medium has boomed, so has the need for people adept in both the art and the technology of 3-D animation: Five of 2010’s 10 top-grossing films were animated, A-list live-action directors such as Steven Spielberg and Gore Verbinski have recently begun working in the genre, and visual-effects driven movies such as “Avatar” rely heavily on animators working with computers. Starting pay for animators varies wildly, but $40,000 to $60,000 is typical in Hollywood, according to the Animation Guild.

While some film schools offer animation majors, they don’t award an undergraduate degree in the field. Most top animators working today studied at art schools, not university film programs.

“Animation was just obvious,” said Elizabeth M. Daley, dean of USC’s School of Cinematic Arts of the school’s expansion of its animation offerings from a few courses to a graduate program in 1995, and now a bachelor’s degree. “Get rid of the words ‘special effects.’ They’re not special. This is the cinematic vocabulary now, and animation is a critical part of that.”

For students such as Kaitlyn Yang, the goal to enter the movie business started when she saw the first “Harry Potter” movie at age 10. “I was watching the Sorting Hat scene, thinking, ‘How do they do that?’” Yang said in an interview a few weeks before graduation, as she and her classmates were in the final throes of their senior projects. Yang’s project was a short film that combines live action and photo-real CG animation to tell the story of a traveling taxicab with a bar inside it. Outside of school, she freelances on the visual effects team for the Fox show “House.”

Daley, the dean, said Katzenberg and Ed Catmull, president of Walt Disney Animation Studios and Pixar Animation Studios, pressed USC for a program that was about more than drawing.

“When you’re training animators, you’re training people how to see, how to capture those subtle things that take place in our actions and our movements,” said Catmull. But the addition of computers, via the field of 3-D animation, has increased the skills animators need to know since Walt Disney’s days, he added. “There are no firm lines anymore between the artistic side and the technical side.”

Kathy Smith, chair of the school’s John C. Hench Division of Animation and Digital Arts, said USC wanted the animation students to draw on the breadth and depth of a research university. “We want them to be able to be thinkers and problem solvers,” she said, “to take courses in astrophysics, in gerontology, to learn the physiology of aging.”

This environment is a long way from how most of Hollywood’s animators learned their craft. Many were self-taught, using instructional books like those by Disney and MGM animator Preston Blair.

“There really were very few schools of animation until the 1970s,” said animation historian Jerry Beck, editor of the blog Cartoon Brew. “Before that, if you were lucky enough to work at Disney, the studio itself was an education.”

Walt Disney paid for members of his animation staff to attend art school classes, and offered courses at his studio. In 1961, seeking more structured instruction for his artists, Disney founded the California Institute of the Arts, which would go on to train many of today’s most prominent directors in animation such as John Lasseter, Brad Bird and Tim Burton.

By Rebecca Keegan

(Los Angeles Times)

(McClatchy-Tribune Information Services)