Aims to promote consumption of locally-grown foods amid wave of FTAs

Community-supported agriculture, farmers’ cooperative markets and other “eat local” projects are springing up in Korea, touting the benefits of locally-grown foods amid an influx of imported produce.

The consumer movement, in vogue in many Western countries for some years, brings a ray of hope to Korean farmers struggling to survive the rising tide of free trade globalization.

For conscientious consumers, it means new alternatives to Western industrial agriculture giants that dominate grocery shelves.

“Many rural communities are interested in the local food movement, for it promises farmers a steady stream of revenue and consumers a supply of fresh harvests at cheaper prices,” said Jeong Eun-mi, a researcher at the Korea Rural Economic Institute.

|

Customers look at vegetables at a store run by the National Agricultural Cooperative Federation in southeastern Seoul. (Kim Myung-sub/The Korea Herald) |

“They see it as a chance to revitalize rural economies, which have lost their vibrancy over decades with the decline of agriculture in Korea.”

The local food movement, or locavorism, aims to build a locally based food economy in an era of globalized, industrial food systems, by linking consumers directly to small-scale farmers and food producers in the area.

The claimed benefits of eating local produce are far ranging ― from freshness, taste and community cohesion, to helping the economy, the environment and even national security.

“Eat local” has been a popular catch phrase in many Western countries. In the U.S., for one, thousands of farmers’ markets thrive, allowing local farmers to sell directly to the area’s consumers. Initiatives such as a “100-Mile Diet” gained popularity, urging consumers to buy food grown within 100 miles (161 kilometers) of their home.

Efforts to make this a norm in Korea are palpable.

Starting from June, Seoul’s urban farmers will sell their fresh harvests at an open-air market set up every Saturday in Gwanghwamum, the heart of the bustling city.

In Wanju, North Jeolla Province, the nation’s first store for local food opened last May, with a promise “from farm to shelf in less than a day.”

Farming communities are landing deals with schools or big corporations in their areas to supply them with their products.

For Cho Min-jung, a mother of two living in Gwacheon, the local food movement is about a sense of safety and trust in food she feeds her children.

“Like Shintoburi, locally grown food is really the best for us,” she said, citing an old Korean idiom which literally translates as one’s body and earth are not two separate things.

She said she has low trust in the safety of imported food, especially from Japan and China, Korea’s closest neighbors ― Japan because of radiation fears and China after a series of food safety crises there.

Cho buys fresh organic vegetables, fruit and meat from a local consumer co-op store near her home, which sources directly from farmers in neighborhood cities in Gyeonggi Province to more distant provinces of Chungcheong, Jeolla and even Jeju Island.

A strict localvore may ask whether Cho is really buying “local,” suggesting that local food should be limited to that grown within a certain radius of her home.

Yet, in Korea, the local food movement is taking off with little discussion of its definition. For many Koreans, it seems that food produced within the country is local enough, given the thousands of kilometers that imported food travels to reach consumers here.

Food produced in distant parts of the globe is fast making inroads into Korean kitchens, a trend reinforced by free trade agreements that the country has signed in the past few years.

According to a recent study by the National Institute of Environmental Research, Koreans consumed 468 kilograms of imported food on average in 2010, up from 410 in 2001.

Koreans turned out to be eating more foreign agricultural products than consumers in three other countries ― Japan, Britain and France. The average for Japanese was 370 kilograms, 26.5 percent less than that of Koreans.

“While the three comparative nations saw a decline, or the status quo, in per capita consumption of imported food, Korea’s dependence on it has increased, driven by grains, vegetables, and fruits,” said Lee Dong-won, a researcher at the institute.

Moreover, the country is increasingly buying food produced far away, he pointed out.

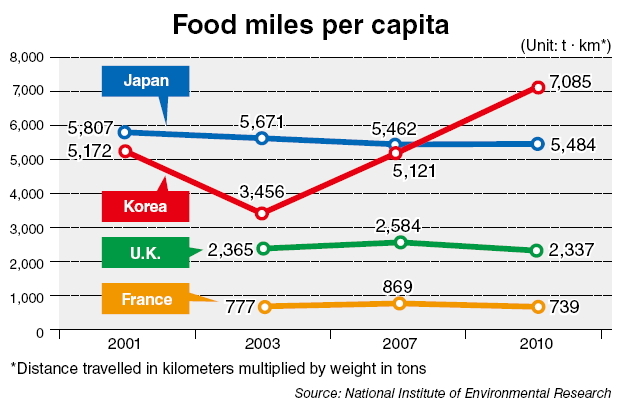

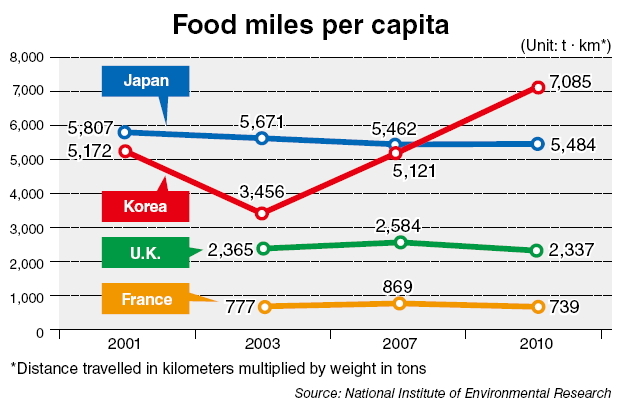

The food miles, which measure the distance food has travelled from farm to plate, jumped 37 percent from 2001-2010 from 5,172 kilometers to 7,085 kilometers.

Over the period, the three other countries all reported a decline ― Japan from 5,807 to 5,484; Britain from 2,365 to 2,337 and France from 777 to 739.

Higher food miles mean less freshness and more carbon dioxide emissions in the process of shipping and transportation, the report said.

“Nearly 70 percent of food we eat is imported from overseas and we know little about how it is produced and processed,” Choi Won-byung, chairman of Nonghyup, or the National Agricultural Cooperative Federation said.

Koreans’ newfound interest in local farms also reflects a growing concern over food security, experts say.

Korea started opening its long-protected food market to foreign agricultural giants in the ‘80s. In 2004, the country implemented its first FTA with Chile, despite fierce opposition from farmers.

Last March, another signature deal went into effect, linking the Korean economy to the U.S., the world’s largest economy and biggest agricultural exporter. Now, the government is pushing for another mega-deal with China.

Korea’s food self-support level was over 80 percent in 1970s, before industrialization and the market opening, but dropped to as low as 34 percent in 1985.

It stood at slightly over 50 percent in 2009, the lowest among members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The figure for grains only, including rice, a staple of Korean cuisine, was 26.7 percent.

Last year, global food crises prompted the Korean government to raise its self-sufficiency targets and pledge 10 trillion won ($8.4 billion) over the next decade to reach them.

Its target for grains is 30 percent domestically produced by 2015, up from the previous goal of 25 percent.

By Lee Sun-young (

milaya@heraldcorp.com)