At a glance, Korean cinema seems to be having a renaissance.

In a world where Hollywood blockbusters dominate the silver screen, local films grabbed a market share of 60 percent in 2013, double that of U.S. titles.

Not only that, ticket sales exceeded 200 million for the first time in history last year, as Koreans once again proved themselves to be among the world’s most avid cinemagoers.

Then this summer came another major milestone.

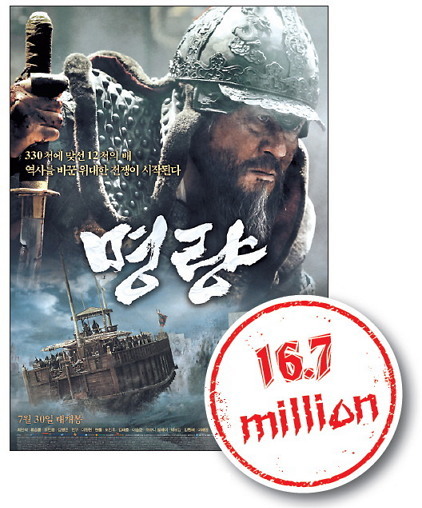

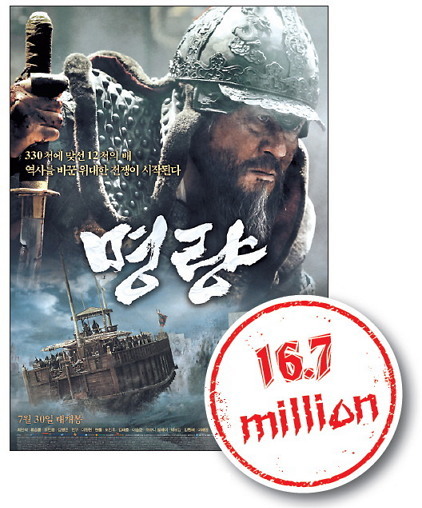

A local period flick, “Roaring Currents,” attracted more than 17 million viewers, the largest number in Korean cinema history. The previous record was 13 million set by the 2009 Hollywood sci-fi flick “Avatar.”

This means that 1 in every 2.8 people in this country of 50 million ― almost everyone in cinema-going age groups -― has watched the story of Adm. Yi Sun-sin, one of the nation’s most revered heroes from the Joseon era (1392-1910).

|

An electronic information board at a local cinema chain shows the times for “Roaring Currents” in this photo taken in August. (The Korea Herald file photo) |

Critics cite a combination of factors for the film’s success: the story of a true hero when Koreans long for someone to look up to and lessons on morality and leadership, all peppered with cinematic brilliance.

Nevertheless, the film’s triumph reignited a heated debate over the conglomerate-controlled film industry and how its moneymaking machine works to churn out megahits at the price of diversity.

“To me, the figure ― 17 million -― is not something that I can be just happy about, because it invokes some very profound and weighty issues,” Kim Han-min, the film’s director, said at a forum held on Oct. 8 in Busan, apparently mindful of the issue.

Vertical integration

It is a familiar story with the Korean economy and its towering conglomerates, but the Korean film industry, too, is led by a few large firms that control all levels of the filmmaking process ― from investing and distributing to screening.

The first chaebol to enter the film market was Samsung in 1992, but following the 1997 financial crisis the company backed out to focus on its core businesses.

The second generation was paved by CJ, Lotte and Orion, which entered the market through CJ Entertainment, Lotte Entertainment and Showbox-Mediaplex, respectively.

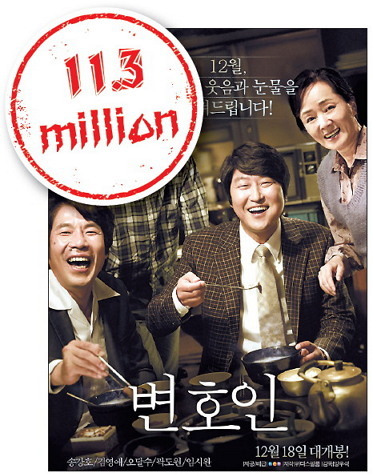

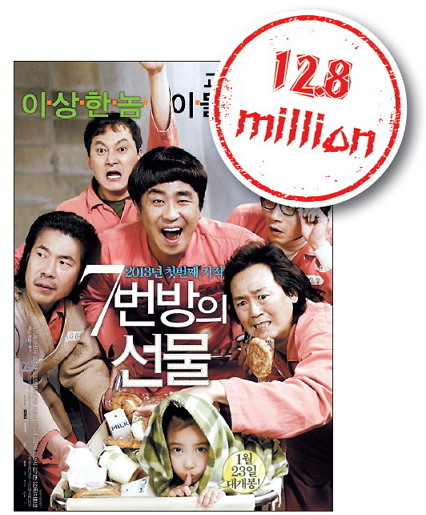

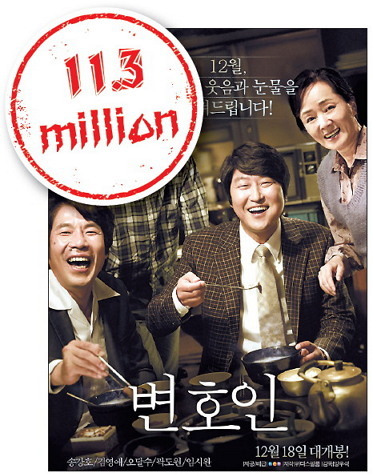

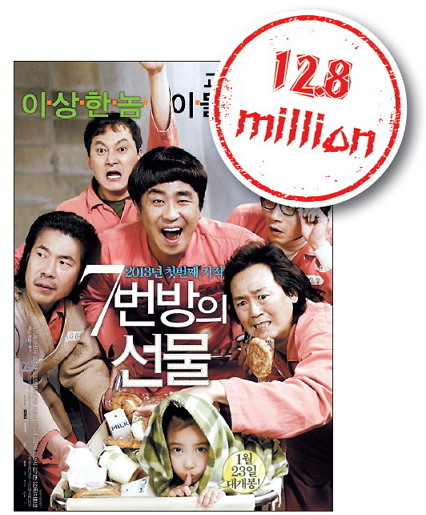

A small but strong rookie player, Next World Entertainment, emerged in 2008, rolling out box-office hits including “Miracle in Cell No. 7” and “The Attorney,” which both exceeded the 10 million viewer mark in 2013.

|

“The Attorney” (NEW, 2013) |

|

“Miracle in Cell No. 7” (NEW, 2013) |

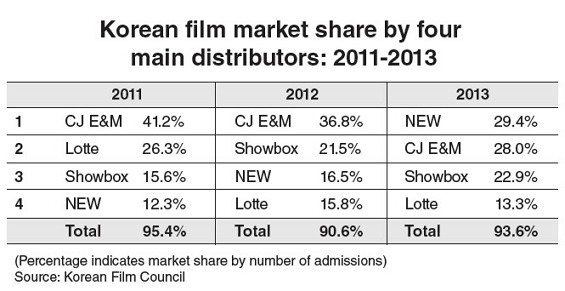

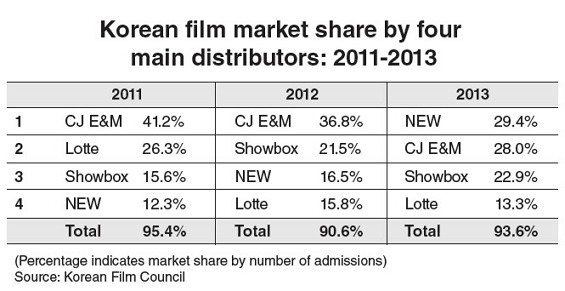

These four major distributors now occupy more than 90 percent of the Korean film market’s audience share. Two of them operate their own theater chains, too ― CJ CGV and Lotte Cinema, the nation’s two largest multiplex chains.

This vertical integration has improved efficiency, channeled more investments into local films and helped bring larger audiences to cinemas.

At the same time, movies made on shoestring budgets and art house films face certain barriers, industry insiders say.

“It is no longer news when distributors who have their own theaters promote their films and give them preferential treatment over other films,” said Choi Yong-bae, vice chairman of the Korean Film Producers Association, at a forum on the monopoly in the Korean film market held at the National Assembly in September.

“They give priority to their films by giving them more screens and more seats, better time slots and arrays of promotions and advertisements in the theater,” Choi commented.

For this reason, many art house films and films distributed by small companies end up not being advertised, being screened during less popular time periods and disappearing from theaters after only a few weeks, he added.

When “Roaring Currents,” distributed by CJ E&M, opened in local theaters in August, it competed with two large-scale period flicks: “The Pirates” (Lotte Entertainment) and “Kundo: Age of the Rampant” (Showbox).

|

“Roaring Currents” (CJ E&M, 2014) |

“The Pirates” garnered 8.6 million viewers, placing second after “Roaring Currents,” while “Kundo” took third place with 4.7 million viewers.

During the peak of its success, “Roaring Currents” was shown on 1,586 of a total 2,608 screens, 61 percent of all the screens in the nation.

CJ E&M took 55.2 percent of the box office in August (32 million tickets) with “Roaring Currents” and six other films it distributed, while Lotte’s distributor took up 22.6 percent. Both NEW and Showbox had single-digit market shares, according to the state-run Korean Film Council.

Diversity is the issue While the industry celebrated three new entries ― with “Roaring Currents” being the latest ― to the club of 10 million viewers in 2013 and this year, it has become increasingly harder for independent, shoestring budget films to survive.

“I knew at first that screening my film ‘Another Promise’ in February would be difficult because all the companies (I approached) decided not to invest in the film in the first place,” said director Kim Tae-yun at the National Assembly forum.

Kim was able to raise funds through crowd-funding and produce the film, which is based on a true story about a worker who contracted leukemia while working at a Samsung Semiconductor factory.

“But I didn’t realize screening would be this difficult.”

His film had secured around 300 screens for the premiere. But on the film’s opening week, one large theater chain backed out without giving a reason. The film was screened at only a handful of screens around the nation.

“There are countless films out there that won’t get a chance to be screened due to politics of conglomerates and (Korea’s) investor-centered industry,” said the director, stressing that a film’s life and death is determined by large conglomerates.

A lack of diversity is also an issue for movie fans.

Lee Hyun-woo, an office worker in his 20s, said he wishes to see more art house films in the theater. “I am disappointed when some films disappear from the theater after only a week.”

Another frequent theatergoer, Kim Young-eun, 33, said, “Sometimes, the films I want to watch in the theater are scheduled during an awkward time such as early in the morning or very late at night, because they are less popular than the blockbusters.

“So I end up watching any film that is on when I visit the theater.”

As calls for change grow, 26 organizations, including representatives from major film organizations, three major multiplex chains (CJ CGV, Lotte Cinema and Megabox) and four major distributors (CJ E&M, Lotte Entertainment, Showbox and NEW), gathered on Oct. 1 to enter into a voluntary industry pact calling for fairer competition.

The agreement requires theaters to disclose their screen allotment criteria and guarantee that all films are screened for at least a week.

“We have to ask ourselves, ‘Who are we making movies for?’” said director Kim Tae-yun.

“For the Korean film industry to prosper in the long term, the industry and the government have to provide a stage where small companies and creative directors can freely produce diverse and unique films,” said Choi of the producers’ association.

By Ahn Sung-mi (

sahn@heraldcorp.com)